December 27th, 2008 admin

A picture I took for We English during the freak snow storm we experienced on April 6 is published in today’s Saturday Telegraph Magazine in their ‘2008 from A to Z’ issue.

I know I promised not to talk about the weather again, however, my picture appears on the ‘W for Weather’ page! The caption reads- “Britain has long been accustomed to April showers, but the snow that affected much of the country on April 6 may take a bit of getting used to. Yet, as the four seasons that we all once enjoyed separately blurred into one, there was at least some semblance of stability provided by a traditional British summer – of widespread floods.”

Tandridge Playing Fields, 2nd April 2008 © Simon Roberts

In a similar round-up of the news in 2008, today’s Guardian features an article by Decca Aitkenhead where she recalls the year’s best and worst times. It provides quite an interesting context for the year in which I produced We English. You can read it here.

Posted in MISCELLANEOUS | 2 Comments »

December 23rd, 2008 admin

Here’s a poem by Benjamin Zephaniah featured in the BBC’s Made in England series to help get you in the festive spirit!

Talking Turkeys by Benjamin Zephaniah

Be nice to yu turkeys dis christmas

Cos turkeys jus wanna hav fun

Turkeys are cool, an turkeys are wicked

An every turkey has a Mum.

Be nice to yu turkeys dis christmas,

Don’t eat it, keep it alive,

It could be yu mate an not on yu plate

Say, Yo! Turkey I’m on your side.

I got lots of friends who are turkeys

An all of dem fear christmas time,

Dey say ‘Benj man, eh, I wanna enjoy it,

But dose humans destroyed it

An humans are out of dere mind,

Yeah, I got lots of friends who are turkeys

Dey all hav a right to a life,

Not to be caged up an genetically made up

By any farmer an his wife.

Turkeys jus wanna play reggae

Turkeys jus wanna hip-hop

Havey you ever seen a nice young turkey saying,

‘I cannot wait for de chop’?

Turkeys like getting presents, dey wanna watch christmas TV,

Turkeys hav brains an turkeys feel pain

In many ways like yu an me.

I once knew a turkey His name was Turkey

He said ‘Benji explain to me please,

Who put de turkey in christmas

An what happens to christmas trees?’

I said, ‘I am not too sure Turkey

But it’s nothing to do wid Christ Mass

Humans get greedy and waste more dan need be

An business men mek loadsa cash.’

So, be nice to yu turkey dis christmas

Invite dem indoors fe sum greens

Let dem eat cake an let dem partake

In a plate of organic grown beans,

Be nice to yu turkey dis christmas

An spare dem de cut of de knife,

Join Turkeys United an dey’ll be delighted

An yu will mek new friends ‘FOR LIFE’.

You can also watch Zephaniah deliver the poem here.

Posted in MISCELLANEOUS | 1 Comment »

December 18th, 2008 admin

I’m currently reading a book called Landscape and Power, edited by By W. J. Thomas Mitchell. The book, originally published in 1994, reshapes the direction of landscape studies by considering landscape not simply as an object to be seen or a text to be read, but as an instrument of cultural force, a central tool in the creation of national and social identity.

As Mitchell writes in his introduction- “Landscapes need to be decoded, they don’t merely signify or symbolise power relations; it is an instrument of cultural power. Landscape is a dynamic medium, in which we live and move and have our being, but also a medium that is itself in motion from one place of time to another…Landscape circulates as a medium of exchange, a site of visual appropriation, a focus for the formation of identity.”

In reference to my last post on Dutch painting, there’s a fascinating essay by Ann Jensen Adams called ‘Competing Communities in the Great Bog of Europe: Identity and Seventeenth-Century Dutch Landscape Painting’. You can read it on google books here.

As Adams identifies, historically the Dutch have maintained a unique and tangible relationship with their land. According to a popular Dutch saying- God created the world, but the Dutch created Holland, referring to the largest land reclamation project attempted in the history of the world, which took place in the 16th Century.

Posted in LANDSCAPE, RESEARCH | Comments Off on LANDSCAPE AND POWER

December 17th, 2008 admin

It was Sarah’s birthday yesterday and we spent the day in London taking in a couple of exhibitions, the Byzantium 330-1453 at Royal Academy and Bruegel to Rubens – Masters of Flemish Painting at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace.

‘Bruegel to Rubens’ is the first exhibition mounted of Flemish paintings in the Royal Collection, bringing together 51 works from the 15th to 17th centuries, including masterpieces by Hans Memling, Jan Brueghel, Van Dyck and Rubens. For me, the most impressive painting in the exhibition was Massacre of the Innocents (1565-7) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, which was acquired by Charles II. On first sight the painting appears to be a scene of a Flemish village under snow, but recent infrared images reveal that it in fact depicts the biblical story of the Massacre of the Innocents, when according to the gospels, King Herod, after hearing of the birth of the King of the Jews, ordered that all children under the age of two should be murdered.

Massacre of the Innocents, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1565-7

You can listen to an audio commentary about the painting here.

The subjects of religion and classical antiquity were frequently represented in Bruegel’s paintings. However, they were often depicted completely integrated into the pastoral life, as in the example of his painting ‘The Census at Bethlehem’.

The Census at Bethlehem, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1566

For this painting, Bruegel has selected an afternoon in winter, with the red sun already touching the horizon and the square full of people despite the cold. Living conditions in the 16th century were very cramped with all the members of a household often housed together in one room. For these reason, people spent more time on the streets and in the village square than in their houses. Children are enjoying themselves on the ice. A heavily pregnant Mary is on the donkey being led by Joseph past a tavern where crowds are gathered on the bottom left of the picture. The main area of the painting is filled with people enjoying themselves, dancing, drinking, paying marbles or practising archery. At the bottom edge of the picture, a man in fool’s costume is leading two children by the hand. It’s said that by including this figure, Bruegel is seeking to tell the observer that he is not only endeavouring to entertain with his portrayal of people enjoying themselves (in this instance at a religious festival) but also wishes to admonish him: Foolishness leads people astray.

Many Flemish and Dutch artists around this time incorporated everyday milieu into their pictures, painting not only rich and important men but also nameless people – the peasants, the agricultural workers, their dwellings and villages. In relationship to my own work, We English is not just a social or cultural commentary although there are elements of this in the work; more, it aims to constitute a sensitive, resolved response to scenes of ordinary people in their chosen environments. And my photographic approach to the project was certainly partly inspired by some of these 16th and 17th century landscape painters.

Enjoying the ice, Hendrick Avercamp, 1630-34

Painters like Hendrick Averamp who depicted winter scenes teeming with life: skaters, men working, children playing, women walking, an entire town engaged in various activities on the ice (above and see my previous post on his work). These vibrant scenes capture people at leisure in a manner that reveals much about daily life but is executed with a transformative vivacity and narrative energy that makes it much more than an anthropological study.

Winter scene with mill, Jacob van Ruisdael, private collection

The work of artists such as Van Ruisdael were executed in a way that also informed my aesthetic gaze. I admire the muted tones of colour, the deceptive flatness of a scene, the way in which individual figures are both dwarfed by and are vital to the landscape around them; even Ruisdael’s preoccupation with local landscape formations, such as dunescapes, must have created for his viewers a sense of recognition and shared regional history. It seems that Ruisdael’s romantic sensibility is successfully assimilated into realistic, recognisable landscapes and this was my intended way of working too.

The beach at Scheveningen, Adriaen van de Velde, 1658

I’m also drawn to Van de Velde’s The Beach at Scheveningen, with its huge skies and opaque stretches of water; a scene full of detail that belies its initial simplicity. During the seventeenth century artists increasingly depicted the sea and beaches along the Dutch coast as places of contemporary life, embodying the national identity of the young Republic. They appear to capture daily life rather than record great events.

As the exhibition catalogue from a previous show (From Russia) at the Royal Academy, identified-

“Art feeds on art and this exhibition demonstrates that all artists draw on the work of their immediate and recent contemporaries or on the art of the past to fine new solutions to creative expression.”

Posted in ART & LEISURE, INSPIRATION | Comments Off on DUTCH LANDSCAPES

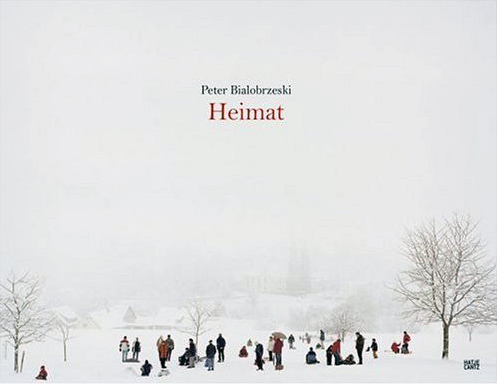

Given the time consuming nature of scanning, I’m going to take this opportunity to return to the blog and look at the work of the second German photographer – after Joachim Brohm – in my Easy Rider series. The photography of Peter Bialobrzeski (born 1961).

I first met Bialobrzeski in 2003 when I was a student on the World Press Photo Joop Swart Masterclass in Amsterdam. He was one of the Masters, along with François Hebel, MaryAnne Golon, Roberto Koch, Manoocher, Nicole Robbers and Tom Stoddart. Looking back over my career over the past ten years I’d say that the Masterclass rates as one of the most significant waypoints in my professional life. It was a hugely valuable experience and, slightly ironically, precipitated my move away from editorial photography. The advice I gleened from the Masters, particularly from Bialobrzeski, was one of the motivating factors for upping sticks and spending a year traveling across Russia working on Motherland. I found an affinity with Bialobrzeski’s work and his approach, which seemed considered, intelligent and contemplative. Not to mention, beautiful.

Bialobrzeski came to prominence with his 2004 book Neon Tigers (which was chosen as one of the Best-Designed German Books of that year and won several prizes including a World Press Photo). However, the work that I am most drawn to is his book on Germany. Heimat (published by Hatje Cantz) which is German for “homeland,” is the fascinating result of his journey over two years, covering nearly 9500 miles around the country.

As with Russians relationship with the concept of Rodina, for Germans Heimat is a rather difficult term which embodies conflicting tendencies. In Bialobrzeski’s own words, “Having a home means having roots, which is not the same as being rooted to the spot.” And since he is more interested in images than in places, Heimat is “not a book about Germany as homeland per se.” Rather, it creates a fixed image of “a personalized bit of visual and cultural history.” He talks about home not being a geographical marker, “it’s not about places, it’s about pictures†he says.

Heimat 08 © Peter Bialobrzeski

Bialobrzeski terms his photographs in Heimat as “projection surfaces for post-postmodernist man’s yearning for nature.†In his preface to the book he pays homage to German Romanticism, in particular the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich (who he identifies as influencing his notions of the ‘German Landscape’) and at the same time makes a nod to the work of contemporary American colour photographers, particularly Joel Sternfeld and American Prospects.

Heimat 20 © Peter Bialobrzeski

The link with Romanticism is clearly evident in these photographs, which Bialobrzeski himself identifies as- “although superficially documentary, with a sort of critical look, the pictures are nonetheless ‘beautiful’ as aesthetic statements.†While they are photographs of ordinary landscapes, unspectacular rural places that have been altered by man and through Bialobrzeski’s lens, are always peopled, they are definitely beautiful, while not slipping into romantic clichés.

Heimat 25 © Peter Bialobrzeski

In an introduction to the book, Ariel Hauptmeier writes “Bialobrzeski wanted to circumnavigate the dogma that art has to be critical, detached, and unemotional. Wanted to set off in the confidence of finding things beautiful that you’re not allowed to find beautiful: ordinary, splendid, uneventful, magical, prosaic German landscapes. Such as everyone knows and loves, such as we have anchored in our collective unconscious. It would have been easy to have photographed these scenes in a cool, fragmented, or even ugly manner. But Peter Bialobrzeski made the effort to find them beautiful.â€

Heimat 15 © Peter Bialobrzeski

The link with German Romanticism and Bialobrzeski’s photographs is extended by Ariel Hauptmeier, who makes sees Bialobrzeski’s last photograph in the book (Heimat 34), that of a young woman sitting alone by the sea, as a pastiche of Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea.

Heimat 34 © Peter Bialobrzeski

Caspar David Friederich, Monk by the Sea (1809), Oil on canvas

Heimat is my favourite photography book of the past couple of years. It’s well worth spending time with. And you can see more of Bialobrzeski’s photographs from the series on L.A.Galerie’s website here.

In a recent conversation where I brought up my We English project, Bialobrzeski told me that he’d actually spent a year in Britain documenting the country between 1991-1992 for a project called ‘Give My Regards to Elizabeth’. The work was shown at Side Gallery in 1993, however, it was never published as a book. I’ve posted up a couple of pictures below, and you can see a larger selection of images here (it’s interesting to see how Bialobrzeski’s pictorial approach has shifted since these were taken).

© Peter Bialobrzeski

© Peter Bialobrzeski

© Peter Bialobrzeski

If you want to find out more about Bialobrzeski’s work, you can read a recent interview with him over on Conscientious here.

Posted in EASY RIDER, HOMELAND, INSPIRATION | 1 Comment »

After a couple of months pouring over the contact sheets (and having a baby in between), I’ve got my edit down to roughly 250 photographs, which I’m now scanning. At this stage I’ve got a pretty good idea of the best fifty, but by scanning a larger edit I’m able to spend more time with each photograph (as well as see them at a much better resolution than on a contact sheet). I find this process very valuable in validating my edit. Once scanned, I’ll then produce some test prints and start playing with layouts. Chris Boot will also assist in the editing process to help whittle the photographs down to a much tighter number for the book.

Posted in POST PRODUCTION | 2 Comments »

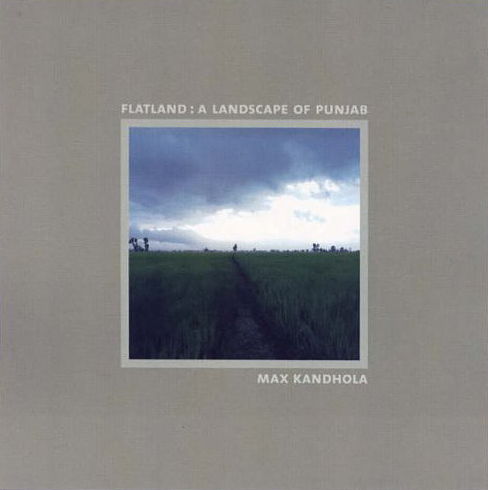

I was fascinated to find out more about Max Kandhola’s body of work ‘Trilogy’ which I touched upon in my last post. Having been in touch with Max, he’s kindly sent me an introduction to the series, which I’ve quoted below alongside some photographs from Flatland (the second part of the trilogy).

“Since the mid nineties I have embarked upon a personal odyssey in mapping my family heritage, Sikh Punjabis, dealing with my life and journey, a social and political mapping of living in England since my parents arrived in the 1950’s. Identity and the notion of home is still firmly imbedded in the motherland for the diasporic Punjabi.”

Kapurthala District travelling between Phagwara and Phillaur Jalandhar District © Max Kandhola, 2004

“Rite of passage, rituals, belief, cast and mysticism, have played and performed their role within the psyche of first generation Punjabis in England. This influence and persuasion can be suffocating, misplaced and at times divisive leading to insecurity. My family are successful in all forms of business, lawyers, accountants, doctors, property developers and the infamous corner shop. Second and third generation Punjabis are looking beyond the veil of scepticism and guilt and beginning to challenge preconceived ideologies and perception about identity, what Indian or Punjabi is in the 21st century living in England.”

Gurdaspur District between Pathankot and Kathua (Jammu & Kashmir State) off the Jammu Road © Max Kandhola, 2006

“My life is in England, my mother, father and brother have been cremated and have had there ashes placed within running water within the lakes and rivers of this country. What is it to be a Punjabi in England. I speak Punjabi; understand the language. My mannerisms are English, yet when I speak Punjabi, the movement of my arms and head tend to elaborate and mimic the rhythmic tone and vocabulary of the forms and sounds generated by the Punjabi vocal chord. It’s quite beautiful and liberating.”

Jalandhar District near Village Saidhowal © Max Kandhola, 2006

“My personal insight and journey is through photography, which adds to the various chapters of contemporary art and literature, unfolding new narrative in placing diasporic Punjabis within a context of further critical discussion. My story is about home, England, my parents, death and dying, the Punjab and diaspora, homeland a new beginning, second and third generation Punjabis, and identities in England. Using archive material, random snapshots and new commissioned and personal work, I will be bearing witness to a family saga, spanning over several generations in discussing ancestral narratives.”

Fatehgarh Sahib District between Humayunpur and Sarai Banjara on route to Rajpura in Patiala District © Max Kandhola, 2004

“Illustration of Life (Dewi Lewis Publishing and Light Work New York 2003) is the first part of a trilogy, which began in 1996, in documenting his father’s struggle with cancer, and his last moments in life, which also explored issues within Sikh ritual, immortality and death. In the final pages of that book are three photographs of Kandhola’s father’s ashes. In Punjabi tradition the ashes are scattered in running water, a physical link re-introducing the body back into the land. Using this as metaphor Kandhola used death as a reference in his exploration of the Punjab land as resurrection of the body, in Flatland A Landscape of Punjab (Dewi Lewis Publishing 2007), which forms the second part of the trilogy.”

Kapurthala District near Khera Majja © Max Kandhola, 2004

“In Flatland A Landscape of Punjab, Kandhola documented the Punjab landscape, researched over a period of four years (2003-2007). Using the backdrop of cities and uncharted villages he has used the location of the rivers and the surrounding landscape as a metaphor in discussing aspects of Sikh Diaspora, the themes of memory and migration. The Photographs in Flatland constitute a photographic discourse of isolation and arcadia, the fantasy of mythological and scared places of cremation, a rugged terrain surrounded by meadows and pastoral land rather than the reality of urban city life. The photographs refer to the historical symbolism of land, and through the juxtaposition of iconographic references its association with Sikh Punjabi’s living in England.”

Patiala District near Rajpura © Max Kandhola, 2004

“In the final part of the trilogy, Roti Kapra aur Makhan, (Food Cloths and shelter), which Kandhola is currently researching, he will document the mundane and the vernacular, new family portraits and archive from the 1950s. The quote has been taken from a 1970’s bollywood film, and also within a social and political context referring to Indira Gandhi who used this verse to comment on the development and growth of the working people of India in 1970, and most recently by the late Benazir Bhutto for the PPP Pakistan People Party, that there will be bread, clothing and shelter for all.”

Travelling through Hoshiarpur District into Gurdaspur District over looking Himachal Pradesh © Max Kandhola, 2006

“Roti Kapra aur Makhan, the term is a metaphor for new beginnings, a cultural reference in discussing ancestral homes, ontology of the family through portraiture, and material culture. Mapping geographical roots and the topography of change from first to third generation Sikhs from Punjab. The narrative will present recognized and unfamiliar metaphors in discussing change and the mystical and mythological antidotes in referencing old and new ideologies of cultural change and extreme views and perceptions on life.”

Morning sky over Firozpur and Rajasthan © Max Kandhola, 2005

Posted in HOMELAND | 4 Comments »

Another photographer whose work deals with questions about identity and memory, mapping ancestral narratives through history and heritage is that of Max Kandhola.

Born and raised in Birmingham, Kandhola is a fine art photographer and Course Leader of Photographic Studies at Nottingham Trent University. His most recent book is Flatland: A Landscape of Punjab 2003-2006, published by Dewi Lewis in September 2007-

Following the death of his father, Kandhola returned to his birthplace in the region of Punjab, the region nestled between India, Pakistan and the region of Jammu and Kashmir. Literally translated as ‘The Land of the Five Rivers’ (‘punj’ is ‘five’; ‘aab’ is ‘rivers’), this is the spiritual birthplace of Sikhism. Intended to counteract stereotypical depictions of Punjab as a dusty, bustling urban area, he composed landscapes referencing Western artists such as Constable and Monet. Flatland is the second in a photographic trilogy of works related to family, memory and the geographical landscape of Kandhola’s cultural heritage, specifically his experience of life in Britain as a second generation Punjabi. He has said:

“My visual composition has inevitably been influenced by English landscapes and gardens. The British suburban garden is a part of British identity. And for many Punjabis who live in England, cultivation of the land – its nurturing and its produce – is both a lasting memory and an association with Punjab, as it was for my father.”

© Max Kandhola, Flatlands

In his first book in the trilogy, Illustration of Life (Dewi Lewis Publishing & Light Work New York 2003), Kandhola photographed his father in the final stages of terminal illness. His intensely personal and honest images confront us with the intimate and often painful reality of death.

The last book in the series Roti Kapra ate Makhan (Food Cloths and Shelter) is a work in progress, and explores contemporary Sikh life in England, through a collection of vernacular photography documenting Kandhola’s extended family, (portraiture) history and archive.

You can read an interview with Kandhola discussing the work here.

Posted in EASY RIDER, HOMELAND | Comments Off on FLATLAND

While reviewing portfolios at Rhubarb Rhubarb’s Cultivate event in Nottingham last week I came across the work of graduate photographer Sam Hofman. His project Aliens Order, deals with notions of his heritage and family roots, in much the same way as Adam Golfer’s work, which I discussed in this blog post.

© Sam Hofman, 2008

I asked Sam to explain the ideas behind Aliens Order, and this is what he told me:

“Poland has always been a place of curiosity to me, ever since I was young I was proud to be of Polish blood. My Grandfather Eryk, came to England when he was 20, but not out of choice, he came here by war and could not return to Poland because of communistic regime. Times have changed and people come and go as they please. There is a difference of intent with the new migration to England, a choice. The expansion of the EU meant thousands of Polish could brighten their future in England by working. Their relationship to England is different, to that of Eryk’s. In this project, I have been exploring notions of my Polish heritage, and the Poles’ relationship to England. Poland is a strong Roman Catholic country and their mass migration to England has revived many churches.”

© Sam Hofman, 2008

“By visiting my unmet family in Poland I began to uncover my Grandfathers life back in Poland before he was conscripted not far from my age. By photographing his remaining siblings, the landscape, and the house where he grew up, which was very much untouched. I have used photography as a tool for a deeper understanding of self-reflection, but at the same time discovered the wider context of current Poland, both culturally and politically. As well as their movements in England, I have juxtaposed images taken in Poland as well as in England, to break down the borders of the two countries. I find it interesting the fact that they have left behind their country in search of something more. Other people in Poland I met wanted to stay in Poland and make it work.”

© Sam Hofman, 2008

You can find a larger selection of images from this project on Sam’s website.

Posted in EASY RIDER, HOMELAND | 2 Comments »