December 17th, 2008 admin

It was Sarah’s birthday yesterday and we spent the day in London taking in a couple of exhibitions, the Byzantium 330-1453 at Royal Academy and Bruegel to Rubens – Masters of Flemish Painting at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace.

‘Bruegel to Rubens’ is the first exhibition mounted of Flemish paintings in the Royal Collection, bringing together 51 works from the 15th to 17th centuries, including masterpieces by Hans Memling, Jan Brueghel, Van Dyck and Rubens. For me, the most impressive painting in the exhibition was Massacre of the Innocents (1565-7) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, which was acquired by Charles II. On first sight the painting appears to be a scene of a Flemish village under snow, but recent infrared images reveal that it in fact depicts the biblical story of the Massacre of the Innocents, when according to the gospels, King Herod, after hearing of the birth of the King of the Jews, ordered that all children under the age of two should be murdered.

Massacre of the Innocents, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1565-7

You can listen to an audio commentary about the painting here.

The subjects of religion and classical antiquity were frequently represented in Bruegel’s paintings. However, they were often depicted completely integrated into the pastoral life, as in the example of his painting ‘The Census at Bethlehem’.

The Census at Bethlehem, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1566

For this painting, Bruegel has selected an afternoon in winter, with the red sun already touching the horizon and the square full of people despite the cold. Living conditions in the 16th century were very cramped with all the members of a household often housed together in one room. For these reason, people spent more time on the streets and in the village square than in their houses. Children are enjoying themselves on the ice. A heavily pregnant Mary is on the donkey being led by Joseph past a tavern where crowds are gathered on the bottom left of the picture. The main area of the painting is filled with people enjoying themselves, dancing, drinking, paying marbles or practising archery. At the bottom edge of the picture, a man in fool’s costume is leading two children by the hand. It’s said that by including this figure, Bruegel is seeking to tell the observer that he is not only endeavouring to entertain with his portrayal of people enjoying themselves (in this instance at a religious festival) but also wishes to admonish him: Foolishness leads people astray.

Many Flemish and Dutch artists around this time incorporated everyday milieu into their pictures, painting not only rich and important men but also nameless people – the peasants, the agricultural workers, their dwellings and villages. In relationship to my own work, We English is not just a social or cultural commentary although there are elements of this in the work; more, it aims to constitute a sensitive, resolved response to scenes of ordinary people in their chosen environments. And my photographic approach to the project was certainly partly inspired by some of these 16th and 17th century landscape painters.

Enjoying the ice, Hendrick Avercamp, 1630-34

Painters like Hendrick Averamp who depicted winter scenes teeming with life: skaters, men working, children playing, women walking, an entire town engaged in various activities on the ice (above and see my previous post on his work). These vibrant scenes capture people at leisure in a manner that reveals much about daily life but is executed with a transformative vivacity and narrative energy that makes it much more than an anthropological study.

Winter scene with mill, Jacob van Ruisdael, private collection

The work of artists such as Van Ruisdael were executed in a way that also informed my aesthetic gaze. I admire the muted tones of colour, the deceptive flatness of a scene, the way in which individual figures are both dwarfed by and are vital to the landscape around them; even Ruisdael’s preoccupation with local landscape formations, such as dunescapes, must have created for his viewers a sense of recognition and shared regional history. It seems that Ruisdael’s romantic sensibility is successfully assimilated into realistic, recognisable landscapes and this was my intended way of working too.

The beach at Scheveningen, Adriaen van de Velde, 1658

I’m also drawn to Van de Velde’s The Beach at Scheveningen, with its huge skies and opaque stretches of water; a scene full of detail that belies its initial simplicity. During the seventeenth century artists increasingly depicted the sea and beaches along the Dutch coast as places of contemporary life, embodying the national identity of the young Republic. They appear to capture daily life rather than record great events.

As the exhibition catalogue from a previous show (From Russia) at the Royal Academy, identified-

“Art feeds on art and this exhibition demonstrates that all artists draw on the work of their immediate and recent contemporaries or on the art of the past to fine new solutions to creative expression.”

Posted in ART & LEISURE, INSPIRATION | Comments Off on DUTCH LANDSCAPES

September 13th, 2008 admin

We visited Berwick-upon-Tweed last week, a town where L.S.Lowry spent a significant amount of time over the course of four decades. He visited the town many times from the mid-1930’s, often on holiday with his family, until the summer before he died. This gives me a good excuse to post up some of my favourite Lowry paintings, as part of my series on the Art of Leisure.

Laurence Stephen Lowry (born Stretford, 1887; died Glossop, 1976) was the only child of Robert and Elizabeth Lowry. He started drawing at the age of eight and in 1903, he began private painting classes which marked the start of a part-time education in art that was to continue for twenty years. In 1904, aged 16, Lowry left school and secured a job as a clerk in a chartered accountants firm, he remained in full time employment until his retirement at the age of 65. His desire to be considered a serious artist led Lowry to keep his professional and artistic life completely separate and it was not disclosed until after his death that he had worked for most of his life. He initially studied evening classes at The Manchester College of Art under Pierre Adolphe Valette a French impressionist painter one of whose specialities was urban scenes of Manchester. Later he learned the art of portraiture from the American painter William Fitz. It was from these artists that Lowry developed his trademark of stylised figures upon an industrial background.

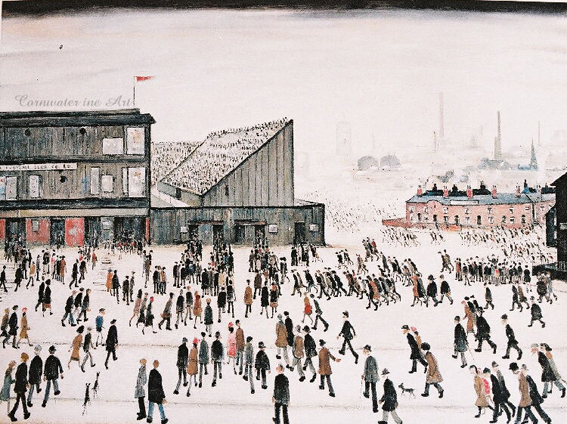

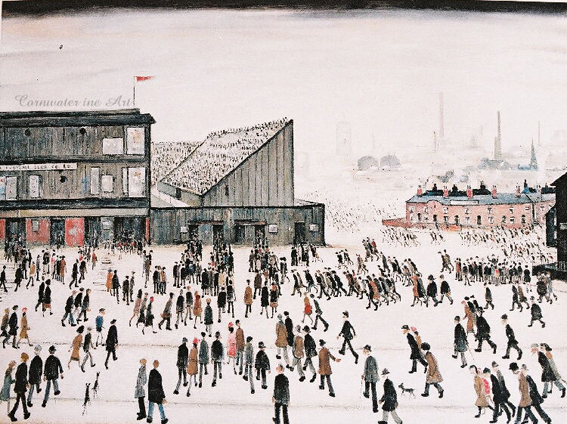

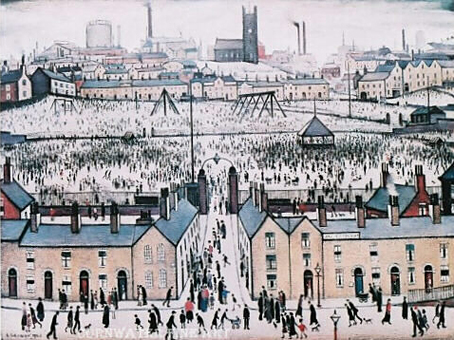

“Going to the Match” 1928, a painting which clearly depicts St. Michael’s Flags and Angel Meadow Park, Manchester.

In 1909, when in his twenties, Lowry moved to Pendlebury, where he spent much of rest of his life and drew inspiration from the mills and factories. In 1916, whilst waiting for a train, Lowry became fascinated by the workers leaving the Acme Spinning Company Mill; the combination of the people and the surroundings were a revelation to him and marked the turning point in his artistic career. Lowry now began to explore the industrial areas of South Lancashire and discovered a wealth of inspiration, remarking ‘My subjects were all around me … in those days there were mills and collieries all around Pendlebury. The people who work there were passing morning and night. All my material was on my doorstep.

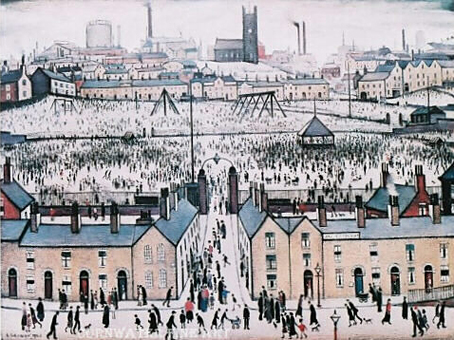

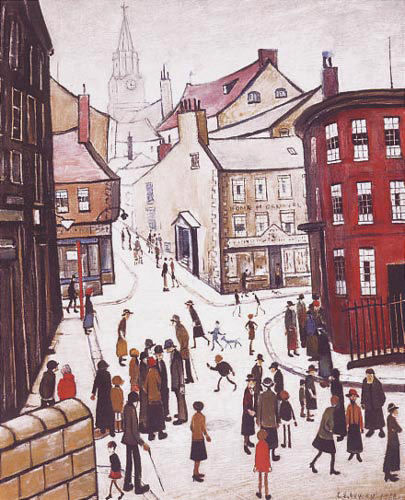

“Peel Park” 1927

Typical of Lowry’s urban landscapes, this is a vivid record of life in industrial northern England. His use of spindly figures, often termed ‘matchstick men’, have become the best-known feature of his work. In early paintings, each ‘matchstick’ figure was carefully and individually depicted. From about 1930, they became less distinctive – anonymous members of the crowd. Although he often depicted industrial cityscapes with some affection, Lowry also conveyed a sense of their bleakness. He invariably used drab colours to portray grimy urban buildings and overcast skies, dominated by ever present smoking factory chimneys.

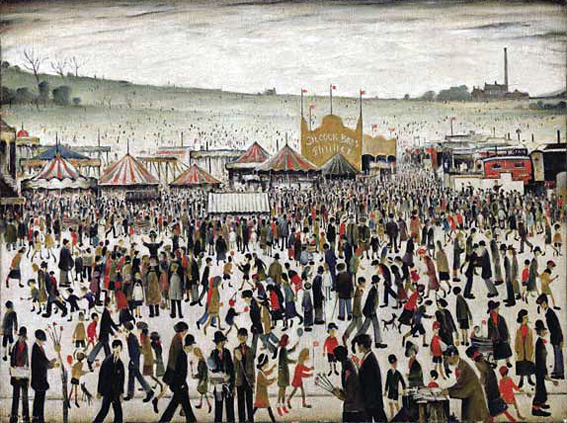

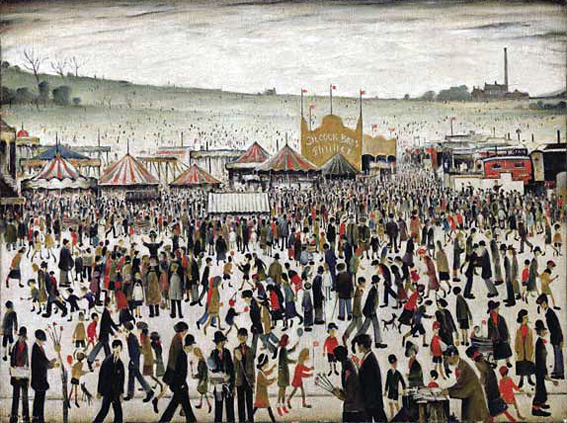

“Good Friday, Daisy Nook” 1946

This painting portrays the Lancashire town of Daisy Nook in festival mood. Traditionally, mill workers were confined to only two statutory days of holiday every year; Good Friday and Christmas Day. Every year on Good Friday, the town of Daisy Nook would stage a fair and provide entertainment to the local crowds. Managed by the Silcock family, whose name appears in the background of the painting, the fair regularly attracted huge numbers of people and still takes place to this day. The present painting depicts this annual fair in 1946, the year after the end of the hostilities of the Second World War. The Ashton Reporter stated at the time that there were ‘Record crowds at Daisy Nook’, as people celebrated a return to the fair and a return to normal life. The painting reflects post-war cheer and relief and depicts crowds of energetic, colourful characters, many holding whirligigs and flags.

On 8th June 2007 Daisy Nook was sold for £3,772,000, the highest price paid for one of his paintings at auction.

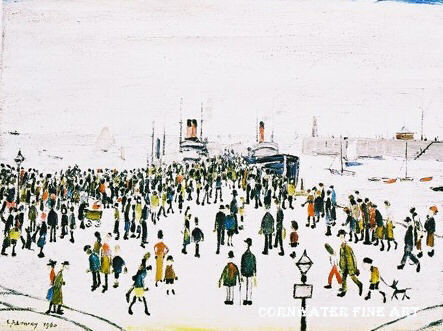

“Britain at Play” 1943

Lowry’s street scenes, peopled with workers, housewives and children set against a backdrop of industrial buildings and terraced houses had become central to his highly personal style. From now on he painted entirely from experience and believed that you should ‘paint the place you know’. Lowry’s leisure time was spent walking the streets of Manchester and Salford making pencil sketches on scraps of paper and the backs of used envelopes recording anything that could be used in his work.

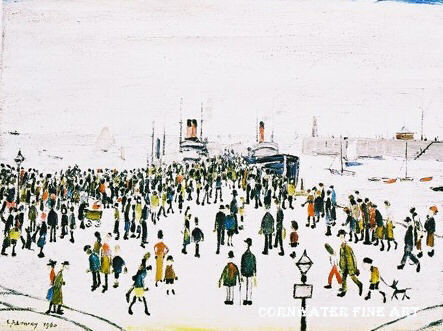

“Ferry Boats” 1960

From his first exhibitions in the 1920s, he built a reputation gradually, only achieving popular success when he was in his sixities, and continued to live a simple and private life. A humble man, Lowry holds the record for turning down the most honours including an OBE. In total he turned down five honour awards and declined the CH in 1972 and 1976.

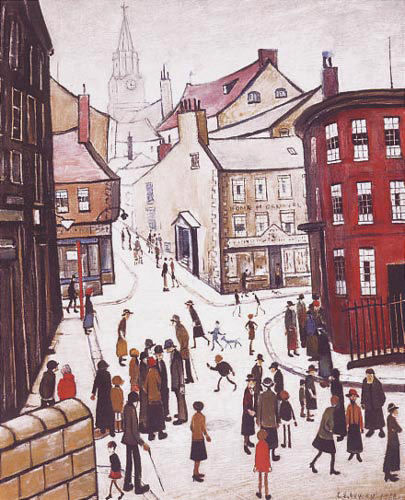

“Berwick Upon Tweed”

To read more about Lowry it’s worth looking at The Lowry Museum’s website here.

There’s an interesting article on the Guardian website by Jonathan Jones written in 2000 when the museum first opened. I’ve quoted a couple of paragraphs from the article here-

“The Lowry paintings worth looking at are the ones everyone knows. There’s no point trying to turn him into a well-rounded artist because he wasn’t one. He was a melancholy compulsive who painted the industrial north of England through deeply disturbed eyes, and caught aspects of it no one else was prepared to look at….Lowry painted the social world of Salford and Pendlebury systematically, illustrating how the factories produced people deprived of identity. His most disturbing images of the working-class crowd depict moments of supposed freedom and leisure: a drawing from 1925 of the bandstand in Peel Park shows people gathering like maggots around a piece of food, while above them the chimneys tower. Again and again he paints the crowd’s attempts at leisure as feeble reproductions of the discipline of the factory. Going to the Match (1953) makes supporting the local football team seem a desperate ritual. One of his scathing images of a crowd trying to forget the factory is called Britain at Play (1943).”

And here’s an article in The Observer by Vanessa Thorpe (March 2007) called ‘Lowry’s dark imagination comes to light’. It explores a much darker, sadder group of Lowry work rarely seen by the public, bleak sketches and paintings that include a series of disturbing and sexually deviant drawings. All had remained hidden until after the artist’s death in 1976. Lowry enthusiast Howard Jacobson argues that ignoring the bleak side of the artist’s imagination has led to him being under-rated and misunderstood by many art critics.

Posted in ART & LEISURE, INSPIRATION | Comments Off on L.S.LOWRY & LEISURE

I’m off to the Epsom Derby tomorrow, so this seems like a good opportunity to post up the wonderfully satirical painting The Derby Day by William Powell Frith.

Â

William Powell Frith, The Derby Day (1856-8). Oil on canvas.

Â

The painting presents a panorama of modern Victorian life and when it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1858, it proved so popular that a rail had to be put up to keep back the crowds. There are three main incidents. On the far left a group of men in top hats focus on the ‘thimble-rigger‘ with his table. In the centre is an acrobat and his son, who looks longingly at a sumptuous picnic being laid out by a footman. Behind them are carriages filled with racegoers, including, on the far right, the mistress of a man leaning against the carriage.

It’s a captivating painting, which naturally, needs to be seen in the flesh. It’s on display in Room 13 of Tate Britain along with a selection of paintings under the heading ‘The Art of Leisure’ (devised by curator Christine Riding). I visited the museum for some last minute inspiration before embarking on this trip, and was lucky enough to have Tony Godfrey from Sotheby’s Institute of Art as my guide. This room felt particularly relevant.

Â

The introductory panel to ‘The Art of Leisure’ reads-

“Queen Victoria died in 1901. During her long reign the enjoyment of leisure time had spread beyond the wealthy upper classes to a wider range of people living in British cities. The lives of working people were hard, but they had greater spending power, shorter working hours and more holidays: more opportunities to enjoy themselves.

A great variety of new activities were on offer: music halls, railway excursions, fairgrounds, commercial exhibitions and sporting events; or just listening to the band in one of the new public parks. The growth of the railways enabled city people to head for the country or seaside for picnics, rambles, swimming and boating. By 1911, just over half of the population of England and Wales made at least one seaside trip every year.

Artists were fascinated with the new leisure activities, but some critics argued that everyday life was not a suitable subject for a painting unless it had a clear moral purpose. The earliest works in this display use narrative and satire to comment on contemporary morality and behaviour. But the guidance offered by later painters, such as James Tissot, is much less clear. In the decades after Victoria’s death, new styles of painting emphasised the light and atmosphere of outdoor leisure activities, rather than the lessons to be drawn for them.”Â

Â

Here are some of the other paintings on display-

Â

Joseph Mallord William Turner Sketch for `East Cowes Castle, the Regatta Beating to Windward’ No. 3  (1827). Oil on canvas.

Â

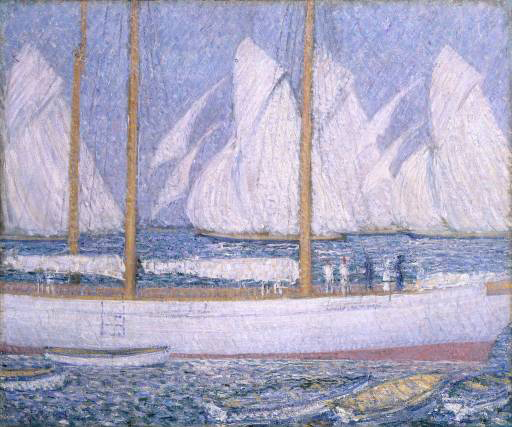

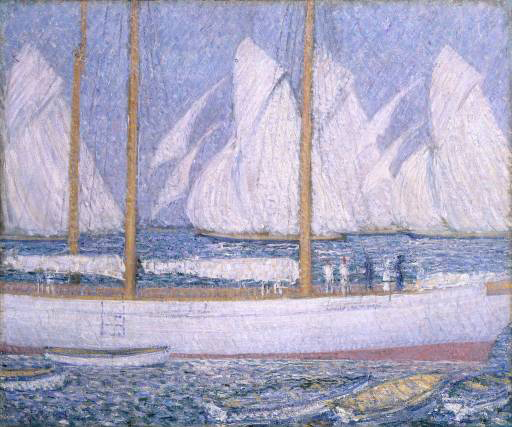

Philip Wilson Steer A Procession of Yachts (1892-3). Oil on canvas.

Â

Sir John Lavery The Golf Course, North Berwick (1922). Oil on canvas.

Â

James Tissot Holyday (circa 1876). Oil on canvas.

Â

Walter Richard Sickert The Front at Hove (1930). Oil on canvas.

Â

Charles Cundall Bank Holiday, Brighton (1933). Oil on canvas.

Â

Philip Wilson Steer The Beach at Walberswick (circa 1889). Oil on wood.

Â

Charles Conder By the Sea: Swanage (circa 1901). Oil on canvas.

Â

Sir Stanley Spencer The Roundabout (1923). Oil on canvas.

Â

Posted in ART & LEISURE, INSPIRATION, RESEARCH | Comments Off on THE ART OF LEISURE

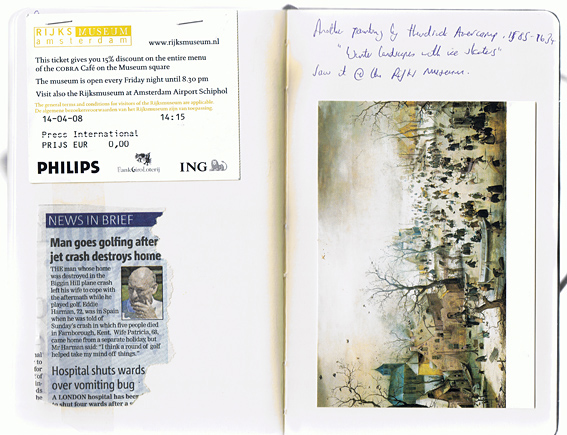

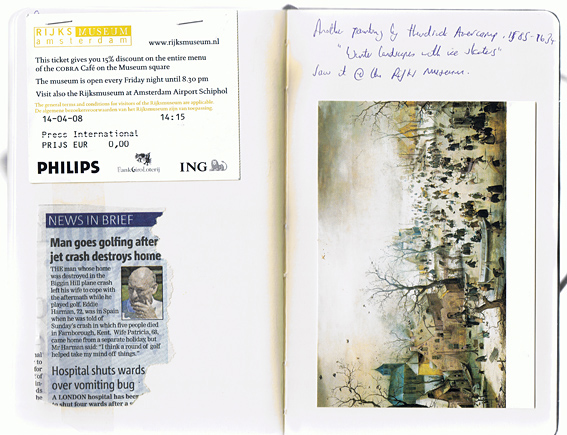

On a trip back from Amsterdam recently I came across a newspaper cutting with an article entitled ‘Man goes golfing after jet crash destroys home’ (see cutting in my scrap book below). A story that goes some way to highlight the sometimes bizarre devotion the English have for sporting pastimes. Eddie Harman, 72, was in Spain when he was told that a plane had crashed into his home in Farnborough, killing five people. His wife came home from a separate holiday to cope with the aftermath, however, Mr Harman played a round of golf before returning to England. He is quoted as saying “I think a round of golf helped take my mind off things.”

While I was in Amsterdam I visited the Rijks Museum. Although the building is currently undergoing major renovation, there is still an opportunity to see a selection of the museum’s masterpieces. A small but wonderful display of Dutch paintings. Given my current interest in leisure, I was particularly taken by Hendrick Avercamp’s ‘Winter landscape with iceskaters’. Avercamp (1585-1634) was one of the first landscape painters of the 17th-century Dutch school, and the most famous exponent of the winter landscape. He was deaf and dumb and known as de Stomme van Kampen

(the mute of Kampen).

Winter Landscape with Iceskaters, c. 1608

In this painting, one of the earliest large winter landscapes in the Rijksmuseum, crowds of people are depicted on the ice in a scene that stretches far into the distance. There is considerable variety among the figures, both in clothing and in what they are doing. Some of those portrayed are having fun, while others appear to be working. Avercamp has included several daring details, such as the couple making love, the bare buttocks and the man urinating.

Another wonderful example of Avercamp’s winter landscapes is: ‘A winter scene with skaters near a castle’ (1585), reproduced here-

I’m going to look at paintings in more detail in a future post. In the meantime, if you have any suggestions of paintings that depict scenes of leisure and pastimes, particularly in the English landscape, please post them below.

A few for starters –

William Powell Frith ‘Derby Day’ (1856-8)

Philip Wilson Steer ‘A Procession of Yachts’ (1892-3)

James Tissot ‘Holyday’ (c. 1876)

Posted in ART & LEISURE, INSPIRATION, TRIP LOGISTICS | Comments Off on A PAGE FROM MY SCRAP BOOK