“These poor villages,

This meagre nature,

Long-suffering land,

Land of the Russian people!”

– Fedor Tiutchev

“The artist should not only paint what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him.

If, however, he sees nothing within him, then he should also omit to paint that which he sees before him.â€

– Caspar David Friedrich, quoted in Romanticism and Art.

The theme of Romanticism has come up several times in the past couple of months; I was recently interviewed by photographer Wendy Pye who was researching her MA dissertation on the links between Romanticism and its influence on twenty first century photography, while a couple of blogs have commented on my work with reference to beauty (see American Suburb X and Ben Huff’s blog). Regular readers of the blog will also have spotted references in my post about Peter Bialobrzeski’s book Heimat – note the obvious reference to Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea and Bialobrzeski’s photograph Heimat 34.

Monk by the Sea, Caspar David Friedrich (1809-10)

Heimat 34 © Peter Bialobrzeski (2002)

Romanticism is an artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the 18th century in Western Europe. The movement stressed strong emotion as a course of aesthetic experience, placing new emphasis on such emotions as trepidation, horror and awe, especially that which is experienced in confronting the sublimity of untamed nature and its picturesque qualities. It was Romantic artists who first asserted the supreme importance of landscape – prior to that it had been subordinate to historical paintings (Titian or Poussin’s principal theme had been nature not man). While the great 17th Dutch painters had been engrossed in the simple depiction of a locality, known as naturalism, it was in Scandanavia (notably in Copenhagen) and Germany that attempts were first made to infuse landscape painting with a sense of the spiritual. Interestingly, the movement took root around the same time as the invention of photography.

While Romanticism can tip easily into parody and melodrama, at its finest, romantic art is overwhelming, beautiful and uplifting. Just think of paintings by JMW Turner, such as this one-

Snow Storm: Hannibal and his army crossing the Alps, JMW Turner (1812)

Writing in the catalogue which accompanied the exhibition Damaged Romanticism, A Mirror of Modern Emotion at The Art Museum of the University of Houston USA (September 2008), Terrie Sultan asserts that “photographers are taking up the Romantic spirit, querying their ability to portray an objective truth and wanting to create images that are open to the interpretation of the viewer.” And Pye notes how several landscape, pictorial and documentary photographers (for example, Nicholas Hughes, Ori Gersht and Elina Brotherus) have adopted romantic styles in some of their work.

In relation to my own work, I certainly wouldn’t deny that I’m an emotive photographer whose images include romantic (with a small r) overtones – elements of intuition, imagination and feeling. To be precise, I would say that I’m more interested in notions of beauty, and what constitutes beauty, rather than specifically applying motifs in my photographs that are linked to Romanticism. Of course, admitting such can be dangerous to your career! Producing romantic, or at least beautiful imagery, is often viewed as profoundly uncool and nostalgic rather than contemporary.

The trouble with beauty is that tastes and standards of what is beautiful vary so much. Take Russia, for instance. In the early 1800s, Russians commonly accepted the European judgement that their land lacked aesthetic value (as a result, Russian landscape painters tended to travel to Italy, where they learnt to capture the brilliant light, or study at the academies of Germany and France). This view of the Russian landscape changed with the outpouring of literary and artistic creativity that followed the century’s political upheavel and artists turned to their native land and revealed the power of gray skies, vast open fields, and simple birch forests.

Mast-Tree Grove, Ivan Ivanovich Shishkin (1898)

In 19th century Russia there was move towards greater naturalism with artists enhancing the idea of Russian beauty and grandeur. The movement was led by artists like Ivan Ivanovich Shishkin (1832-1898) who was famous for his scrupulously detailed canvases depicting the Russian countryside, its impenetrable forests and enormous skies; artists like Arkhip Ivanovich Kuindzhi (pronounced Quind-gee, 1842-1910) whose paintings are characterised by their panoramic sweep, the simplification and stylisation of natural forms; and Isaak Ilich Levitan (1860-1900), who painted ‘mood landscapes’, in which he established an overall atmospheric unity.

Evening Chime, Isaac Ilyich Levitan (1892)

As Christopher Ely argues in his book This Meager Nature: Landscape and National Identity in Imperial Russia (Northern Illinois University Press, 2002)-

“The articulation of a specifically Russian landscape in art and literature contributed to the construction of Russian national identity. This process entailed learning both to view Russia without European aesthetic filters and to love the very features of Russian land and nature that seemed impoverished by comparison with European landscape conventions. ‘Proud foreign eyes’, so important in the late eighteenth-century approaches to Russian landscape imagery, would cease to hold authority by the end of the nineteenth. At the turn of the twentieth century, Russia’s ‘meager nature’ and ‘humble barrenness’ were no longer dull and tedious for Russian viewers, but highly valued, even a ‘blessing’. The meagre, humble, barren and suffering land gave birth to the special strengths, endurance, and soul of the ‘Russian people’. ‘This meager nature’ thus became a font of national celebration. Russian’s came to embrace their land’s modest beauty.”

(On this point, it’s worth noting that one of Romanticism’s key ideas and most enduring legacies is the assertion of nationalism, which became a central theme of Romantic art and political philosophy).

In my approach for Motherland, I was making a deliberate attempt not to produce clichéd representations of a Russia ground down by poverty and despair. Russia was not exoticised, but my gaze certainly attempted to explore this notion of Russia’s “modest beauty”:

Alexandrovsk Port, Sakhalin Island © Simon Roberts (2004)

Golden Horn Bay, Vladivostok © Simon Roberts (2004)

Woodland, Zheleznogorsk © Simon Roberts (2005)

Apartment blocks reflected in water, Okha, Sakhalin © Simon Roberts, 2004

In relation to We English, which was partly inspired by both Turner and another Romantic British artist, Constable, the work is no doubt rooted in the consciousness of my own attachment to England and is at times an unashamedly lyrical rendering of every day landscapes.

Posted in INSPIRATION, LANDSCAPE | 2 Comments »

Another photographer whose work has explored the notion of politicised landscapes is John Darwell in his book, Dark Days (Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2007), which documents the 2001 UK Foot and Mouth Epidemic in the Lake District.

Here Darwell explains the work:

“This work produced around my home on the north side of the English Lake District looks at the Foot and Mouth epidemic that swept through the UK in 2001 and became one of the most devastating and significant events to affect the British countryside within living memory, the aftershock of which will continue to shape the future of the countryside for decades to come. The images look to all affected areas from the Lake District fells closed to walkers to the measures farmers went to in order to keep people away from their farms for fear of infection, to the destruction of millions of farm animals and onto the now notorious pyres. The work then continues by recording the extraordinary efforts undertaken by farmers to eradicate the virus from their buildings; and finally the third part of the work looks at the aftermath of the disease and the gradual reopening of the countryside whilst asking questions about the future of the agricultural economy as more and more farms were put up for sale.”

And here are a selection of the photographs:

Dead lambs by roadside © John Darwell, 2001

Roadside pyre © John Darwell, 2001

Barricaded farm entrance, Southwaite © John Darwell, 2001

Farm gate protest sign reads ‘1 of Blairs Killing Fields’, Lorton © John Darwell, 2001

Disinfection bowl, Near Carlisle © John Darwell, 2001

Disinfection mat on the A6, Shap © John Darwell, 2001

Closed picnic site on M6, Carlisle © John Darwell, 2001

Smoke on road, Welton © John Darwell, 2001

Footpath sign closed, Carlisle © John Darwell, 2001

Bangladeshi schoolteachers disinfecting their feet © John Darwell, 2001

Explaining this last picture Darwell comments “this photograph was taken on the first day the fells were open after the lifting of some the access restrictions. I went up Kirkstone Pass to see what was happening. There were dozens of people prepared to go through disinfection to get onto the fells, mostly runners and keen walkers. Whilst I was watching a coach arrived and dozens of people got off, the ladies in saris and sandals the men in linen suits. They had just arrived from Bangladesh and were on their way to Ambleside to begin teaching at the college there. The coach driver being either a comedian or not quite on the ball suggested a nice walk on the hills to get a sense of the place, hence their first experience of Cumbria was having to place their feet in buckets of disinfectant before walking up a soggy hillside. I had a long chat with some of them and after some initial bemusement most seemed to find it quite funny and an experience to take away with them.”

You can see more images from Dark Days on Darwell’s website here.

A book of Dark Days containing 150 colour images plus text pieces by Liz Wells, Professor Roger Breeze, U.S. government advisor on animal epidemics and viral warfare and Alison Nordstrom, Curator of Photographs, George Eastman House, was published in March 2007 (Dewi Lewis Publishing). It is one of the most complete body of images produced during this period and stands as a testament to those ordinary people caught up in extraordinary events (and political incompetence!). It is a work that asks a number of searching questions, either explicitly or implicitly, about the future direction of food production and of the countryside we wish to visit.

Posted in LANDSCAPE, OTHER STUDIES | Comments Off on DARK DAYS

Following on from Friday’s post Contested Countryside, Cumbria-based photographer Stuart Parker got in touch regarding a project he worked on in response to the trial of Mohammed Hamid. Here he explains the reasons behind ‘Tomorrow We Enter Paradise’ along with a few of the photographs from the project.

“As a photographer Iiving in Cumbria I have an interest in social issues in a landscape context, particularly in the Lake District. The idea for this project stemmed from encountering a group of young Asian men on an early morning walk near Buttermere. It later transpired in the news that so called ‘Jihad training camps’ were being monitored in the Lake District by MI5, which reminded me of the group that I had seen.

I decided to explore the places at which the camps had allegedly been held including Wasdale, Buttermere, Grizedale Forest and the Langdale Valley, the latter being where the MI5 surveillance photographs were taken. The result was a series of photographs drawing on actual and metaphorical links between the Lake District, London and Afghanistan. ”

Buttermere © Stuart Parker

Elterwater © Stuart Parker

Buttermere Cone © Stuart Parker

Campfire © Stuart Parker

Langdale © Stuart Parker

Buttermere Church © Stuart Parker

Little Langdale © Stuart Parker

Limbs © Stuart Parker

Tunnel © Stuart Parker

Posted in LANDSCAPE, OTHER STUDIES | Comments Off on TOMORROW WE ENTER PARADISE

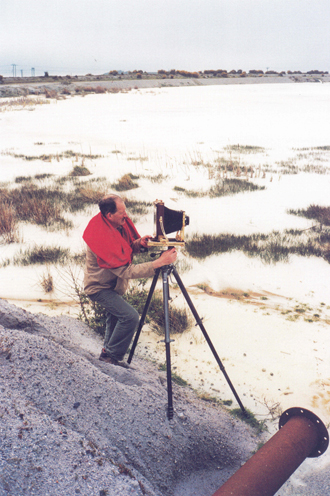

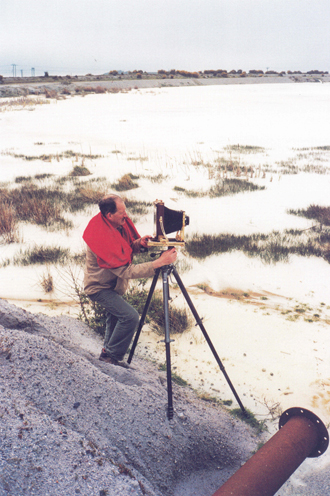

I notice that Jem Southam has an exhibition currently showing at The Lowry until the 22nd March 2009. Clouds Descending is the result of a two year commission where Southam made photographs along the Cumbrian coastline, recording the industrial landscape and harbour towns, which Lowry loved so much.

Southam will be giving an evening lecture at The Lowry on February 6th. There is also the opportunity to take part in an all-day Masterclass with him on Saturday 7th February – full application details are available from redeyesubmissions@googlemail.com

Southam has been a key figure in British photography for over twenty-five years. Working exclusively in the landscape genre, his prevailing thematic concerns are the changes, large and small, occurring within the British countryside. His photographs are the result of patient observation and contemplation over long periods of time. Often producing series, Southam layers and juxtaposes images that not only reveal cycles of nature, but the interactions of humans with their environment. He has said that he proposes “histories,†both social and natural.

Brampford Speke, 1998 from the series Dew Ponds © Jem Southam

As David Evan’s writes in Source magazine, “For his epic theme, Southam adopts appropriate, time-consuming working methods. There is extensive preparatory research, including the study of weather forecasts. There is walking and waiting, frequently on difficult terrain. Bulky equipment is often being carried around, especially a Wista, a modern Japanese version of a Victorian plate camera. Southam only photographs on still grey days, sometimes producing just a few images in a year. The end results are crafted objects, recalling the work of 19th Century pioneers like Carleton Watkins who took along a wagon laboratory pulled by a dozen mules… Southam’s achievement is to create work informed by past and present that has conviction… [He is] the photographer of the slow rhythms of social time and the even slower rhythms of physical geography.â€

To find out more about Southam’s work, read an interview in SeeSaw Magazine here and watch a slideshow of his photographs here.

Southam is represented by Robert Mann Gallery and Charles Isaacs.

Posted in INSPIRATION, LANDSCAPE, OTHER STUDIES | 1 Comment »

December 18th, 2008 admin

I’m currently reading a book called Landscape and Power, edited by By W. J. Thomas Mitchell. The book, originally published in 1994, reshapes the direction of landscape studies by considering landscape not simply as an object to be seen or a text to be read, but as an instrument of cultural force, a central tool in the creation of national and social identity.

As Mitchell writes in his introduction- “Landscapes need to be decoded, they don’t merely signify or symbolise power relations; it is an instrument of cultural power. Landscape is a dynamic medium, in which we live and move and have our being, but also a medium that is itself in motion from one place of time to another…Landscape circulates as a medium of exchange, a site of visual appropriation, a focus for the formation of identity.”

In reference to my last post on Dutch painting, there’s a fascinating essay by Ann Jensen Adams called ‘Competing Communities in the Great Bog of Europe: Identity and Seventeenth-Century Dutch Landscape Painting’. You can read it on google books here.

As Adams identifies, historically the Dutch have maintained a unique and tangible relationship with their land. According to a popular Dutch saying- God created the world, but the Dutch created Holland, referring to the largest land reclamation project attempted in the history of the world, which took place in the 16th Century.

Posted in LANDSCAPE, RESEARCH | Comments Off on LANDSCAPE AND POWER

It’s not often that you come across a landscape, urban or rural, that is virtually unchanged in half a century.

On driving from Malham to Arncliffe, a road which cuts through the picturesque limestone landscape of the South Pennines in the Yorkshire Moors, I came across Les and Doreen Barnett sat on deck chairs looking out over the hills while enjoying a sandwich and flask of tea. Les, who is founder and president of both the Bradford Urban Wildlife Group and Bradford Botany Group, told me that he and Doreen had been coming to admire this view for nearly 50 years. In that time, all that’s changed is a new tractor on the farm and the unwelcome arrival of several roadside salt bins. Traffic is heavier at the weekends, so they only come on a weekday morning.

As W.G.Hoskins writes in his classic text The Making of the English Landscape (1955), “not much of England, even in its more withdrawn, inhuman places, has escaped being altered by man in some subtle way or other, however untouched we fancy it is at first sight.”

Three influences shape landscape- geology, climate and mankind. The origins of the early industrial revolution are to be found in the South Penines, an area which takes in parts of Bradford, Calderdale, Craven and Kirklees in Yorkshire and Burnley, Oldham, Rochdale and Lancashire County Council. These places bear witness to one of the greatest leap forward man has ever made: the Industrial Revolution. This is a cultural landscape unique in England.

While the 19th Century transformed the region – wool in Yorkshire, cotton in Lancashire, textile wealth that powered the Victorian Age and the British Empire – much of this area is still untouched. The Yorkshire Moors are steeply cut by wooded valleys and a patchwork of hamlets and fields. Acid soils on impervious gritstone rock make the moors a tough but beautiful natural environment. Below the rough grazing of the moor, a distinctive lattice of 18th century drystone walls mark out the ‘in bye’ land: winter pasture for lambing and summer moving meadows for silage and hay.

Posted in LANDSCAPE, PLACES | Comments Off on AN UNALTERED LANDSCAPE

Part of my interest in We English is to explore the layers of history in the landscapes I’m photographing. Take this picture of Holkham Beach, on the north Norfolk coastline, which I took earlier this year. The beach has long been a place of pilgrimage for holiday-makers (it was recently voted best ‘British beach for a bank holiday break’ by readers of The Times). However, when you dig a little deeper, the landscape has not always been one of harmony. And it remains a contested place with different groups laying claim to the landscape.

Holkham National Nature Reserve, Norfolk, 18th February 2008

Holkham National Nature Reserve is an extensive reserve on the North Norfolk coastline owned by the Earl of Leicester and the Crown Estates and managed by English Nature and Holkham Estate. As with so much of the English countryside the visual appearance of this stretch of the Norfolk coast is a part wilderness and part constructed landscape. From Burnham Overy to Wells the low-lying marshes north of the coast road used to be tidal saltmarshes, separating offshore shingle and dune ridges from the main coastline. The tidal creeks were large enough to allow ships to load cargo from a staithe at Holkham village. From 1639 onwards a series of embankments were constructed by local landowners, including the Cokes of Holkham. By the time the Wells embankment was completed in 1859 by the 2nd Earl of Leicester about 800 hectares of saltmarsh had been converted to agricultural use. In the late 19th century the 3rd Earl of Leicester planted pine trees on the dunes, creating a shelter-belt to protect the reclaimed farmland from wind-blown sand.

Being close to Sandringham it has also been popular with the Royal Family who occasionally makes visits to their beach hut set back from the dunes. It was particularly popular with the Queen Mother whose own entourage, using the beach back in the thirties, were rumoured to have been responsible for establishing this stretch of sand as a gay beach.

However, the landscape has not always been one of harmony. In the late 1880s, class collisions in East Anglia were most clearly found in areas where people spent their leisure time. While the English understood the codes of behaviour which applied to different social orders in the domestic or work place, these codes were less fixed when people were on holiday. Whole sections of newly mobile classes were likely to meet more often in unpredictable circumstances. The chief attraction of the Norfolk coastline were sports like fishing, shooting sailing and seaside holidays. It was now easy to reach by rail from London, where larger numbers of people had money to spare for holidays. But the numbers and social diversity meant that the middle classes, who were used to distant and uncomplicated relations with the locals, found their holiday-making changed into something much less welcome. Evasion was not always possible, no matter how much it was desired. As John Taylor highlights in his book, A Dream of England, “the fear of class collision meant that the landscape was a place of exclusion and tension, factors deriving from the fascination and repulsion that the middle class felt of the lower classesâ€.

More recently, a moral backlash was sparked when the press were alerted to a campaign by the warden, Ron Harold, to “clean up” the nudist beach popular with local gays. Harold is an employee of English Nature; an organisation ostensibly set up to promote conservation. He declared he would seek a citizen’s arrest on anyone he found cavorting together in the dunes and woods. After a total of five arrests in that first year, Harold erected new signs across the beach prohibiting nudism above the high watermark. The car park prices went up to pay for another warden to assist in the moral policing of the beach.

Posted in LANDSCAPE, REPRESENTATION | Comments Off on LANDSCAPE AS CONTESTED PLACE