Just before Christmas I attended a talk by Ingrid Pollard at Tate Britain as part of their Conversation Pieces series. It got me thing about my previous post talking about landscapes as contested places and I thought it would be interesting to touch upon the visual relationship between rural England, notions of Englishness and ethnicity.

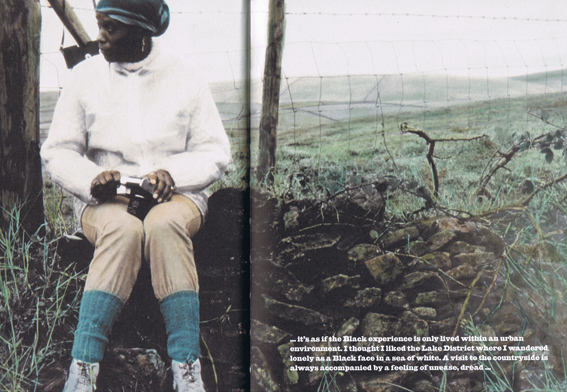

Pollard first came to public attention in 1987 with Pastoral Interlude, a series of photographs about Black people’s experience of the English countryside, particularly the Lake District. Steeped in the heritage of Wordsworth and the Romantic poets, her photographs explore the beauty of the English landscape and coastline, alongside the memories hidden within England’s history and its relationship to Africa and the Caribbean. Her interest in the layers of history is echoed in her use of 19th century photographic techniques.

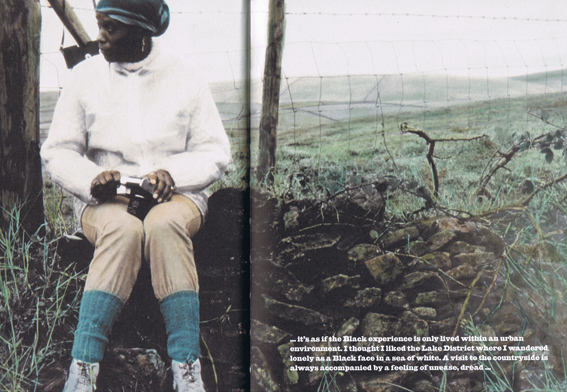

As a Black woman, Pollard articulates in her Pastoral Interlude and Wordsworth Heritage series several levels of alienation and otherness. The landscape of the Lake District, which she sees as epitomizing the ‘authentic’ British countryside, confirms the status of the Black woman as an outsider. For instance, in Pastoral Interlude, Pollard captions a photograph of a lone black female figure in the landscape,

“…it’s as if the Black experience is only lived within an urban environment. I though I liked the Lake District where I wandered lonely as a Black face in a sea of white. A visit to the countryside is always accompanied by a feeling of unease, dread….â€

© Ingrid Pollard

The caption indicates what she takes to be the oppressive homogeneity of visitors to the region. Writing about Pastoral Interlude in her book Postcards Home (Chris Boot Ltd, 2004) Pollard says “There was an unconscious selection of the lone figure within the landscape. It became a way of working. The stylized posed figures, the use of historical details about a particular place. Nothing about the scene is really ‘natural’. It’s as manufactured and deliberate as the assumptions and stereotypes about Black people.â€

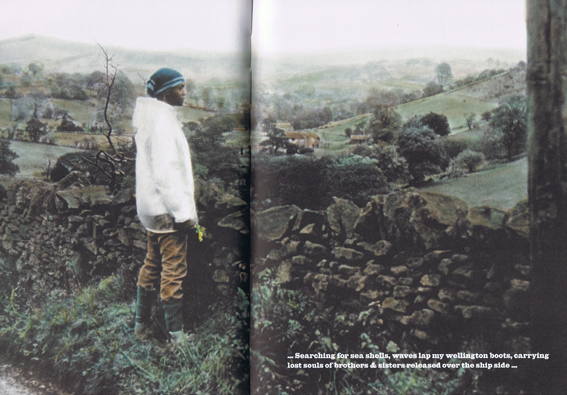

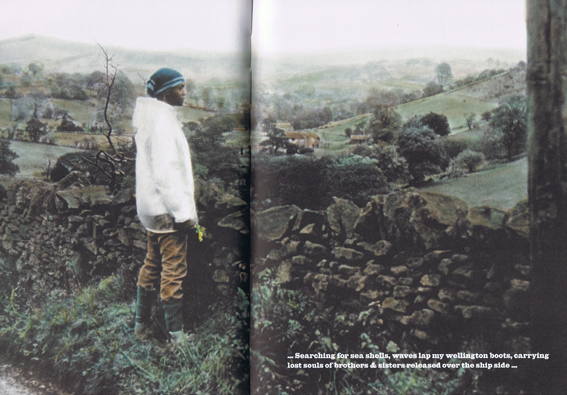

Pollard’s use of surprising, sometimes shocking captions subvert her images which otherwise show someone, who at first glance, looks like they seem to be enjoying themselves in the countryside and appear to be ‘at home’. For instance, another image of herself in the Lake District she captions

“…Searching for sea shells, waves lap my Wellington boots, carrying lost souls of brothers & sisters released over the ship side…â€

© Ingrid Pollard

As John Taylor writes in his book A Dream of England, “despite the commodification of the countryside as a haunt for well-equipped ramblers, following in the footsteps of the Romantics, for Pollard the landscape is disenchanting: the spell it casts as a commodity seeks to discount her as a customer. Her landscapes recall with irony the tradition of eighteenth century British landscape painting, which sought to establish the countryside as the natural domain of the British middle classes.â€

Twenty years after her Pastoral Interlude work was made, I wonder whether Pollard would still find the English countryside as insular and racist as she did then?

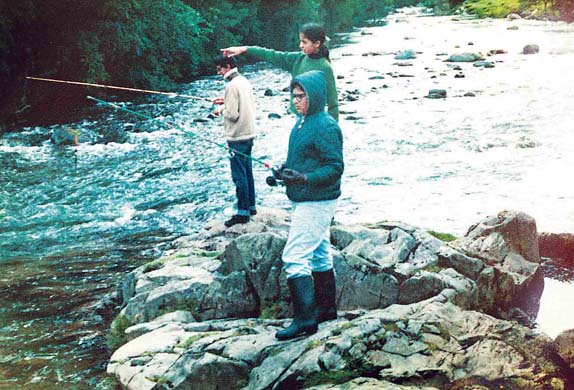

Another photographer, whose work has challenged our stereotypes and conventional readings of English rural landscapes would be John Kippin. Kippin’s work pays allegiance to the conventions and traditions of pictorial landscape whilst foregrounding issues within contemporary culture and politics. Note particularly his photograph ‘Prayer Meeting, Windemere’ taken from a body of work called Nostalgia for the Future.

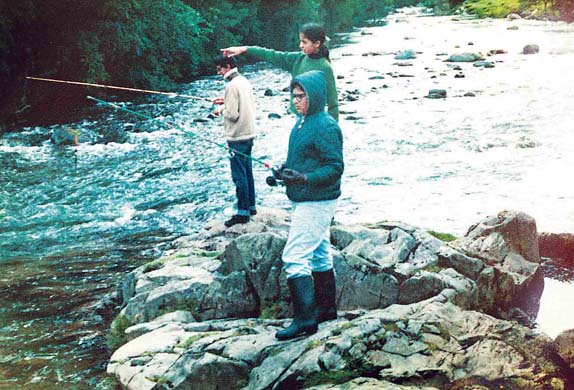

© John Kippin

Describing the scene in Creative Camera (quoted from A Dream of England), Paul Wombell writes that the party are “probably from Lancashire and came to work in the mills, and now they are tourists in this heritage England. It turns the idea of British landscape upside down; who goes there, what meanings can people get†(1992). As Taylor notes “although there is a spiritual tradition to English landscape, prayers in this fashion are quite unconnected to the pantheism or Romanticism which is usually associated with it.â€

This projection of a dominant culture in the countryside can be seen when we look at the preponderance of white, middle-class, middle-aged members of the National Trust (see this article in The Independent).

It was also recently highlighted in a study by the Commission for Racial Equality (2004), which showed that although ethnic minorities make up 8% of the UK population they represented just 1% of visitors to the countryside. The then chairman of the Commission, Trevor Phillips, suggested that a form of “passive apartheid” existed in the British countryside. His comments certainly sparked quite a debate. However, it was interesting to see how many ethnic minorities disagreed with his analysis (see replies posted on the BBC News Online here) and actually felt quite at home in the countryside.

This summer there was an article in The Guardian where four journalists described their memories of holidays in the UK. British born writer Maya Jaggi described her experiences of childhood holidays in the Lake District in the 1970s.

Maya Jaggi, Lake District

“The ingredients of the ideal holiday were fixed for me as a child on a trip to Windermere. After a day on the lake, messing about in a rowing boat with my family, my aunt Madhur gave me a masterclass in boning fish.†She goes on to say “My parents had taken to borrowing a friend’s cottage in the village of Ulpha near Coniston Water. My mother (Madhur’s eldest sister) was head of English in a London school, and was drawn to the Lake poet associations. She would marshal my two older brothers and me to Dove Cottage and Rydal Mount, pointing out the spot where the Ullswater daffodils sprouted. My brothers learned to fish for brown trout in the River Duddon, the inspiration for 34 Wordsworth sonnets (I was keener then on Swallows and Amazons). The riverbanks near Ulpha bridge are now a popular site for picnickers, but we had them much to ourselves.â€

Jaggi makes no reference to her or her family feeling marginalised in the landscape. They seem very much at home. In fact, she goes on to make a connection between the landscape of the Lake District and that of her father’s birthplace of the Punjab-

“For my displaced, cash-strapped parents the Lake District may have been a landscape in which to recreate for us aspects of their own childhoods. My father, whose family lost land in Punjab during Partition, would roll up his trousers and wade gamely into the becks, much to my adolescent embarrassment, while packed lunches on the fells could conceivably stand in for the lavish picnics at Himalayan hill stations that were a mythic part of my mother’s Old Delhi family. After the sisters studied at Delhi University (where my parents met), my mother left for London on her honeymoon, while Madhur, after Rada, settled in Greenwich Village. The English Lakes became a place where a family dispersed across three continents could reassemble.â€

Family pose for a photograph, Bowness-on-Windermere, Lake District © Simon Roberts

In relation to my own journey around England for this project, while I found that much of rural areas in the West Country and Northumbria to be very white, in the Peak District, Yorkshire Dales, North Yorkshire Moors and Lake District I was surprised to witness relatively large numbers of ethnic minorities engaging with the countryside (as Wombell alluded to, this would make sense given the proximity of these rural retreats to large towns and cities with substantial ethnic minority populations, like Burnley, Bradford, Leeds and Blackburn), and seemingly not alienated by the environment.

Climbing the waterfall at Gordale Scar, North Yorkshire © Simon Roberts

Take for example my photograph below of rock climbers on Stanage Edge in the Peak District. In the foreground a Muslim couple wearing distinct grey robes walk on a footpath through the landscape. Our tendency to ‘read’ this view in terms of traditional English activities is hard to resist and the couple therefore seem to be ‘out of place’. On speaking to them I learned that they were from Leicester on a weeks walking holiday, staying at a B&B in the nearby village of Hathersage. They spoke of feeling completely at ease in the area and described how they often spent their holidays exploring the English countryside.

Stanage Edge, Peak District © Simon Roberts

One organization that is trying to engage more ethnic minority groups with rural England is the Mosaic Partnership. Mosaic is an organization forging links between black and minority ethnic community groups across England and Wales with four National Park Authorities (the Peak District, Yorkshire Dales, Brecon Beacons & North York Moors), the Youth Hostels Association (YHA), and the Campaign for National Parks (CNP; formerly the Council for National Parks). They are attempting to promote National Parks as part of our shared cultural heritage, as well as places offering opportunities for physical recreation and spiritual renewal.

You can read accounts written by several ethnic groups who have taken tours in National Parks on Mosaic’s website here.

It’s worth mentioning that there is also a political dimension to landscapes of rural England. Take for example the reporting and politicised nature of the foot-and-mouth outbreak or the trail of Mohammed Hamid, who was jailed in February 2008 for organising al-Qaida style training camps across Britain (read article in The Guardian here). In relation to ethnicity, this latter event is of interest.

Photographs taken by two surveillance officers from Scotland Yard (above) showed Hamid, and several other Muslim men in a group of 23 others, on exercises at a farm in the Elterwater area of the Lake District. In the trial Hamid claimed these were bonding sessions to bring together Muslim men who felt vulnerable after 9/11. But police said he was trying to recruit and train young men for violent jihad. Hamid organised two more camps in the Lakes. The last on 17 August 2004 included 21/7 ringleader Muktar Ibrahim. MI5 officers covertly filmed this gathering. Hamid later organized excercises in secluded sites in the New Forest and paintballing centres in south-east England.

The widespread reporting and publication of these photographs provoked headlines around the world linking rural England with terrorism-

“Training camps for terrorists in UK parks†The Guardian, 14th August 2006

“Holiday trip, or a ‘bomber’ training camp?†Daily Telegraph, 19th January 2007

“Al Qaeda terrorist who took part in Lake District training camp sentenced to six years in prison†Daily Mail, 22nd November 2007

“Network of terrorist camps in rural England – Convictions of 7 militants revealed terror activities in idyllic rural settings†MSNBC, 26th February 2008

“Trial exposes network of UK terror camps” Zee News, 27th February 2008

to be continued….

Posted in OTHER STUDIES, REPRESENTATION, RESEARCH | 5 Comments »

I must say that I’ve been totally underwhelmed by Martin Parr’s much heralded photographic portrayal of ten British cities, which have been running as ‘special’ supplements in the Guardian newspaper over the past few months.

This weekend, the Guardian’s Weekend magazine ran a cover story with a twelve page spread showing a selection of Parr’s photographs under the title ‘Urban Splash- Martin Parr captures the essence of Britain’s cities’.

I’ve not seen the full set of photographs, however, if the magazine’s edit is anything to go by then they appear to be little more than an incoherent selection of snapshots hurridely collated, and furnished with uninteresting and often irrelevant captions. Aesthetically they seem very lazy indeed. Maybe he’s been too busy this year peddling Parrworld? (the largest exhibition to date of his work, which opened at the Haus der Kunst in Munich and is touring the world).

The whole project also appears to be very calculating in terms of its spin-offs, with various box sets (standard and deluxe) and calendars available from the Guardian website here.

I’m not one of those anti-Parr photographers, indeed I’ve long respected him as a practitioner and commentator, however it does seem that he’s missed a real opportunity to produce something interesting and illuminating about Britain, twenty years after the publication of his groundbreaking book, The Last Resort.

Much of his portrayal has certainly been seen as very stereotypical, as illustrated by these comments posted on the Guardian letters page –

“I was dismayed and shocked by Martin Parr’s supplement on Newcastle (British cities: Newcastle, October 27). He introduces his piece: “I first visited Newcastle in the mid-70s and I remember being impressed with Byker, a classic working-class suburb with a tight sense of community and steep terraces. I revisited Byker for this project and found the small shops were struggling, despite Aldi and the Gala Bingo doing well.” This shows he came to Newcastle with the notion of finding that quaint, parochial, grim-up-north picture of the Geordie struggle for survival – a dangerous stereotype to uphold.

Newcastle is no longer a bastion of British industrial power, but a multicultural metropolis often billed the London of the north because of the regeneration that has been applied to all areas of the city. Areas such as the Quayside and Jesmond have welcomed this regeneration, and have seen new life breathed into them, attracting young professionals and students alike.

There are many things Parr could have shot to highlight the urban evolution that is happening within this city. He mentions Grey Street and the stunning architecture of the city centre, but does not show it in any of his photographs. Then there are some of the many attractions that bring people to the city that he missed out in favour of outdated sentiments, such as the Laing Art Gallery, the Tyneside cinema, Blackfriars dining hall, the Tynemouth Priory and Castle, the Jazz Cafe, both universities and any one of the many bridges spanning the Tyne – I could go on.”

Nelson Iley, Newcastle upon Tyne

“Martin Parr’s supplement on Newcastle was billed as one of a series “capturing today’s urban Britain”. What he has actually done is lazily capture all the cliches of Newcastle from 30 years ago. In his 29 photographs, he manages to pack in bingo, greyhound racing, homing pigeons, a double dose of the derelict Swan Hunter shipyard, a greasy spoon cafe, two shots of hen nights, two lots of women with cheap drinks at the races, and a tattooed man prodding his barbecue. While all of the above go to make up some of the rich mixture of life in Newcastle, where are the other sides to the city? Where’s the chic city centre pubs and bars? Where are the 50,000 students? Where are the arts venues? Where is the growing multicultural community? Guess they would not suit the stereotypes Parr set out to portray.”

Graeme King, Newcastle upon Tyne

“Martin Parr seems to have arrived in Newcastle with all his stereotypes in tow, and to have regurgitated them for us with stock images of pigeon fanciers etc. Geographically, the photo essay was inaccurate. It was entitled Newcastle, but included Gateshead and North Tyneside – two areas distinct from Newcastle in the eyes of north easterners.”

Alison Grant and Anna Vaernes, Newcastle upon Tyne

You can see a selection of Parr’s images from the project on the Guardian’s website here.

I’d be interested to hear your comments on the work, if you haven’t already done so on the Flickr group Martin Parr We Love You!

Posted in OTHER STUDIES, REPRESENTATION | 19 Comments »

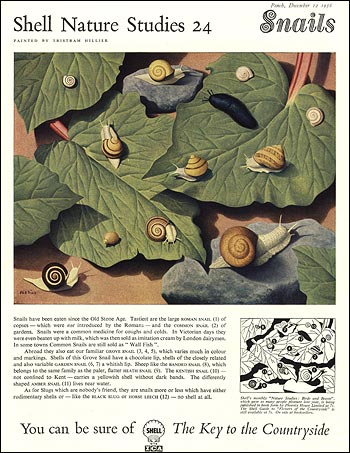

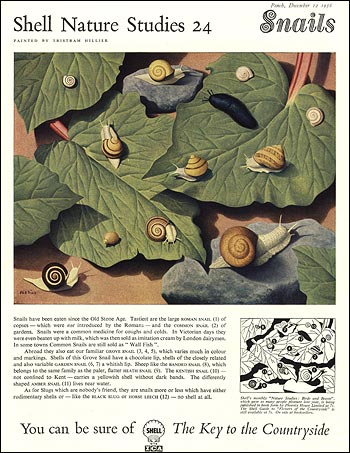

There’s an interesting article in today’s Daily Telegraph by Jack Watkins where he explores the enduring appeal of the Shell travel guides, which published in the first half of the past century.

The Shell Guides were aimed at a new breed of car-driving metropolitan tourists. They were for those who sought guides that were neither too serious nor too shallow and who took pleasure in the ordinary and peculiar culture of small town Britain. In the three decades after the Second World War the Shell Guides provided a “surreptitiously subversive synthesis of the British countryside,” says Dr David Heathcote, curator of an exhibition on the books at the Museum of Domestic Design & Architecture (MODA) in Hertfordshire.

As Watkins notes, “it was the Shell Guides, with their sharp writing and atmospheric black and white photos and pictures, that elevated the medium to an art form.” The first one, on Cornwall and penned by Sir John Betjeman, was published in 1934. It was quickly followed by volumes for Devon, Dorset and Derbyshire, and the series grew, undergoing various revisions, into the 1980s.

“These slender tomes, long edited by Betjeman, were at their best when focusing on small towns and villages”, says Heathcote.

“Metropolitan cities were mostly ignored and instead they plunged enthusiastically into the local, the particular and – above all – the peculiar. Today we’ve got the likes of the Rough Guides, which are only interested in places they regard as ‘cool’ and thus dismiss swathes of Britain as not worth visiting.”

I’m particularly interested in this assertion by Watkins: “The assumption that tourism is merely a glorified consumer experience is bad enough when applied to our oldest towns. It turns them into ‘anywherevilles’, with shopping and eating as the main end purpose. But, in a subtler way, it has even happened to rural parts of Britain. The plethora of national parks and conservation areas does protect fragile aspects of the natural or built heritage, but by default has led to superficial branding by marketing bodies. It has dangerously eroded an appreciation of the locally endearing, or what Betjeman might have called the ‘superficially mundane’.”

For similar discussions on the blog regarding branding and the heritage industry see my previous posts here and here.

The Shell Guides: Surrealism, Modernism, Tourism is at MODA until November 2 (020 8411 5244). The exhibition explores the creative forces that created the Shell County Guides. It considers their widespread cultural influence on our shared understanding of Britain and British-ness.

Posted in REPRESENTATION, RESEARCH | Comments Off on SUPERFICIALLY MUNDANE VS ANYWHEREVILLES

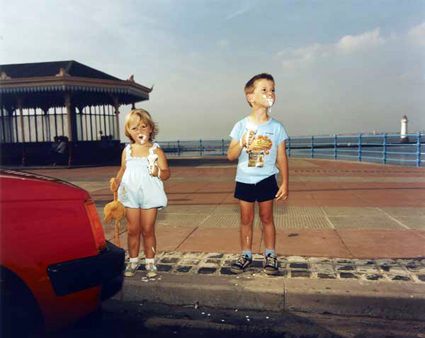

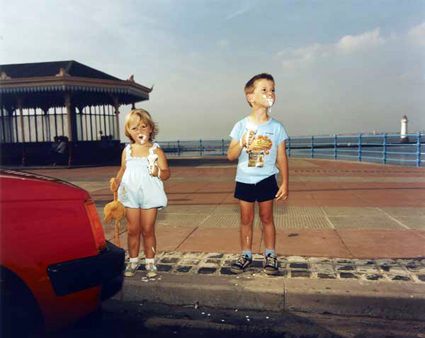

Between 1983 and 1986, Martin Parr photographed holidaymakers and day-trippers in the decaying seaside resort of New Brighton on the Wirral (near Liverpool). Using flash and printing in vivid colour, he shed an unforgiving light on his subjects. The project was published by Dewi Lewis and exhibited at the Serpentine Gallery in 1986 as The Last Resort.

© Martin Parr, The Last Resort

At the time, there was a concerted critical media response to the work with most of the criticism being aimed at the subjects, not the photographs. Since its publication there has been much debate about Parr’s approach to his subject and opinions are very much divided between those who consider his work as cruel and voyeuristic, while others suggest his view is actually affectionate and amusing.

© Martin Parr, The Last Resort

Whatever you think, The Last Resort was a highly original and influential body of work and a wonderful satire on the state of Thatcher’s Britain. It established Parr as one of the world’s most influential and admired photographers, while revolutionising documentary photography in Britain.

© Martin Parr, The Last Resort

So it was rather surreal arriving in New Brighton on a sunny (and rather blustery) afternoon a couple of weeks ago having all the visual baggage of Martin Parr’s photographs in my head. Of course it was an anti-climax. In the name of progress the area has changed considerably since Parr’s days with much of the Wirral’s northern coastline a sought after area, (we were staying with two university friends, a GP and a trainee Consultant, who recently moved to Hoylake from Liverpool).

© Martin Parr, The Last Resort

A £70 million redevelopment plan for the regeneration of New Brighton was unveiled in 2004, with the aim of bringing jobs and tourism into the area. Known as the Neptune Project, it involved filling in the Marine Lake to build a supermarket, and constructing a lido resort combining a pool and a new marine lake. However the plans were rejected on account of financial feasibility, and scepticism over the actual worth to the community on the whole. In October 2007, the Government rejected a public enquiry into the plan, and an amended plan was approved, which will include a Morrisons supermarket on the seafront, budget hotel and refurbishment of the Floral Pavilion Theatre.

While it’s great that the area has managed to develop and shed its tatty appearance, as is so often the case these days, the re-development is very bland and non-descript. You could be on any promenade in England, there is no individuality just lots of concrete. Although I’m sure New Brightoners are much happier than the resort of Parr’s photographs.

As an aside, there’s an interview with Martin Parr in the current issue of PDN called ‘Why Photojournalism Must Get Modern’. In the interview Parr argues that photojournalism “has to get modern†to regain the attention and support of mainstream magazines. He asserts, “You have to disguise things as entertainment, but still leave a message and some poignancy.”  You can read it  online here.Â

Â

Posted in PLACES, REPRESENTATION | Comments Off on FROM LAST RESORT TO NEW RESORT

It turns out that the North-South divide I wrote about in my last post has recently been redrawn in a controversial new study. Interestingly, the study was undertaken by one of the Human Geography professors from my old department at The University of Sheffield.

Professor Danny Dorling has devised the line based on a number of more recent socio-economic developments, including rising house prices, increased life expectancy and voting patterns. Dorling’s line says the North begins at the Severn estuary and heads up towards the Humber, hitting the coast in a higgledy piggledy diagonal south of Grimsby.

You can read about Dorling’s study in an article in the Observer and more about his research on British identity (with Bethan Thomas) here.

Â

Posted in PLACES, REPRESENTATION | Comments Off on A NEW LINE FOR NORTH-SOUTH DIVIDE

According to a recent article in The Times, which quoted a survey conducted by Travelodge hotel group, almost 5m southerners have never travelled north of the Watford Gap – and the cultural barrier, often known as the North-South divide, has become an equal deterrent in the opposite direction.

© David Sillitoe/ The Guardian

Â

The North-South divide is not an exact line, but one that can involve many stereotypes, presumptions and other impressions of the surrounding region relative to other regions. The Times article quotes that almost three-fifths of northerners in the survey described southerners as “snobs†while half surveyed associated London and the home counties with “wide boys†and City brokers in “pinstripe suitsâ€. For southerners, the north is a desolate landscape of derelict mining villages and fish and chip shops, and is dismissed by three-fifths as “bleak†and “unsophisticatedâ€.

The existence of the North-South divide is often contested, although the Watford Gap service station is unofficially known by residents of London and southeast England as the point where the north-south divide occurs.

According to wikipedia, it has recently become more popular to use the phrase “north of Watford“, referring to the larger town. The reason for this change is probably due to the signs at Staples Corner, where the M1 begins, reading simply ‘M1, Watford, The North’ thus potentially implying that Watford is the last place in the South.

In his book The English, Jeremy Paxman proposed that the north might be defined as anywhere above a line drawn from the Severn to the Trent. Whereas Stewart Maconie, in his book Pies and Prejudice, suggests the north begins at Crewe station, beyond which point “the geology becomes harder, the accents flatter and the climate wilder. And the surface of the M6 turns from tarmac to cobbles.â€

Having driven past Watford Gap, the Severn-Trent line and finally passing Crewe train station on Friday, we must officially now be in ‘The North’.Â

Â

Posted in PLACES, REPRESENTATION | Comments Off on THE NORTH

Part of my interest in We English is to explore the layers of history in the landscapes I’m photographing. Take this picture of Holkham Beach, on the north Norfolk coastline, which I took earlier this year. The beach has long been a place of pilgrimage for holiday-makers (it was recently voted best ‘British beach for a bank holiday break’ by readers of The Times). However, when you dig a little deeper, the landscape has not always been one of harmony. And it remains a contested place with different groups laying claim to the landscape.

Holkham National Nature Reserve, Norfolk, 18th February 2008

Holkham National Nature Reserve is an extensive reserve on the North Norfolk coastline owned by the Earl of Leicester and the Crown Estates and managed by English Nature and Holkham Estate. As with so much of the English countryside the visual appearance of this stretch of the Norfolk coast is a part wilderness and part constructed landscape. From Burnham Overy to Wells the low-lying marshes north of the coast road used to be tidal saltmarshes, separating offshore shingle and dune ridges from the main coastline. The tidal creeks were large enough to allow ships to load cargo from a staithe at Holkham village. From 1639 onwards a series of embankments were constructed by local landowners, including the Cokes of Holkham. By the time the Wells embankment was completed in 1859 by the 2nd Earl of Leicester about 800 hectares of saltmarsh had been converted to agricultural use. In the late 19th century the 3rd Earl of Leicester planted pine trees on the dunes, creating a shelter-belt to protect the reclaimed farmland from wind-blown sand.

Being close to Sandringham it has also been popular with the Royal Family who occasionally makes visits to their beach hut set back from the dunes. It was particularly popular with the Queen Mother whose own entourage, using the beach back in the thirties, were rumoured to have been responsible for establishing this stretch of sand as a gay beach.

However, the landscape has not always been one of harmony. In the late 1880s, class collisions in East Anglia were most clearly found in areas where people spent their leisure time. While the English understood the codes of behaviour which applied to different social orders in the domestic or work place, these codes were less fixed when people were on holiday. Whole sections of newly mobile classes were likely to meet more often in unpredictable circumstances. The chief attraction of the Norfolk coastline were sports like fishing, shooting sailing and seaside holidays. It was now easy to reach by rail from London, where larger numbers of people had money to spare for holidays. But the numbers and social diversity meant that the middle classes, who were used to distant and uncomplicated relations with the locals, found their holiday-making changed into something much less welcome. Evasion was not always possible, no matter how much it was desired. As John Taylor highlights in his book, A Dream of England, “the fear of class collision meant that the landscape was a place of exclusion and tension, factors deriving from the fascination and repulsion that the middle class felt of the lower classesâ€.

More recently, a moral backlash was sparked when the press were alerted to a campaign by the warden, Ron Harold, to “clean up” the nudist beach popular with local gays. Harold is an employee of English Nature; an organisation ostensibly set up to promote conservation. He declared he would seek a citizen’s arrest on anyone he found cavorting together in the dunes and woods. After a total of five arrests in that first year, Harold erected new signs across the beach prohibiting nudism above the high watermark. The car park prices went up to pay for another warden to assist in the moral policing of the beach.

Posted in LANDSCAPE, REPRESENTATION | Comments Off on LANDSCAPE AS CONTESTED PLACE

Having frequented countless Tourist Information centres in towns and cities over the past few months, it’s fascinating to see how places market themselves in the hope of attracting tourists. From Broadstairs’ use of Dickens (see my last post) and Suffolk branding itself as Constable Country to the Lake District embracing Wordsworth to Stratford-Upon-Avon employing the strapline “Explore England’s England†(along with Shakespeare Country of course).

This issue of how places represent and brand themselves is something I’ll come back to in a later post, but for the time being I just wanted to talk about Margate, the coastal town in Thanet which has become a by-word for rundown seaside resorts and whose recent decline was immortalized in Pawel Pawlikowski’s stark film Last Resort (2000).

Margate has an important place in the story of seaside holidays. It vies with Scarborough, Whitby and Brighton for the title of England’s first seaside resort. Since the early 18th century, people have been visiting the town to bathe in the sea, first for health reasons, then for pleasure as it became a playground for some of the wealthiest members of London society. With the arrival of railways, visitors who had been restricted to traveling along the Thames could now explore stretches of cast further afield. However, by the eve of the First World War, Margate was as busy as any resort. The town’s small-scale facilities were soon replaced by large hotels and new forms of entertainment for the hundreds of thousands of Georgian holidaymakers who arrived each year.

Margate’s sandy beach with a large group of summer trippers entertained by a minstrel show, 1890s.

The prosperity of the seaside continued until the 1960s,but with growing leisure time, increased disposable income and easy access to foreign holidays, all seaside resorts suffered decline, though none has probably suffered as much as Margate. The town has experience a vicious circle, with decreasing visitor numbers leading to reduced investment and consequently poorer facilities that again attract fewer holidaymakers.

However, it seems Margate has hit upon a plan for renewal which might just help it return it to some of its past glory. The town, along with Thanet and Kent County Council, is turning to art as a vehicle for regeneration and enlisting the help of our most influential painters, no not local bad-girl Tracy Emin (although she is proving quite influential), but rather JMW Turner.

Turner (1775-1851) was a regular visitor to Margate throughout his life, drawn by the quality of the light. He once remarked that ‘the skies over Thanet are the loveliest in all Europe’.

My attempt at a Turner sky, looking out onto the English Channel from our parking space on Margate’s seafront.

The Turner Contemporary gallery has recently received planning permission for a building designed by 2007 RIBA Stirling Prize winner David Chipperfield Architects. Work is expected to start on site (which is situated a few hundred meters from the picture above) in autumn 2008 ahead of the gallery opening in 2010. The successful operation of the gallery is seen as playing a key role in the regeneration of Margate’s eastern seafront and the reinvention of the old town as an artistic quarter.

As you walk around the town there are obvious signs of change. Many of the rundown buildings I’d seen on my last visit here five years ago are being turned into cafes and restaurants (thankfully few of them major chains) and there are already obvious signs that art is playing an important role with a number of community arts projects and workshops springing up around the town. The old site of M&S on Margate’s highstreet is currently housing off site projects for the Turner Contemporary until its opening in 2010.

It is unlikely Margate will ever attract the vast numbers of visitors that flocked there in the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, with growing concerns about the environmental effects of flying and the costs of foreign travel, the English seaside holiday may enjoy some form of revival.

For those of you interested in the topic of representation within the tourism industry, there’s a quarterly journal called Tourism Geographies: An International Journal of Tourism Space, Place and Environment, published by Routledge.

This paper looks particularly interesting-

Tourism consumption and tourist behaviour: a British perspective by Gareth Shaw a;Â Sheela Agarwal b; Paul Bull c

| Affiliations: |

a Department of Geography, University of Exeter, UK. |

|

b Centre for Tourism, Sheffield Hallam University, UK. |

|

c Department of Geography, Birkbeck College, University of London, UK. |

DOI: 10.1080/14616680050082526

Publication Frequency: 4 issues per year

Published in: Volume

2, Issue

3 August 2000 , pages 264 – 289

Order it here.

Posted in REPRESENTATION | 1 Comment »