CONTESTED COUNTRYSIDE

January 16th, 2009 adminJust before Christmas I attended a talk by Ingrid Pollard at Tate Britain as part of their Conversation Pieces series. It got me thing about my previous post talking about landscapes as contested places and I thought it would be interesting to touch upon the visual relationship between rural England, notions of Englishness and ethnicity.

Pollard first came to public attention in 1987 with Pastoral Interlude, a series of photographs about Black people’s experience of the English countryside, particularly the Lake District. Steeped in the heritage of Wordsworth and the Romantic poets, her photographs explore the beauty of the English landscape and coastline, alongside the memories hidden within England’s history and its relationship to Africa and the Caribbean. Her interest in the layers of history is echoed in her use of 19th century photographic techniques.

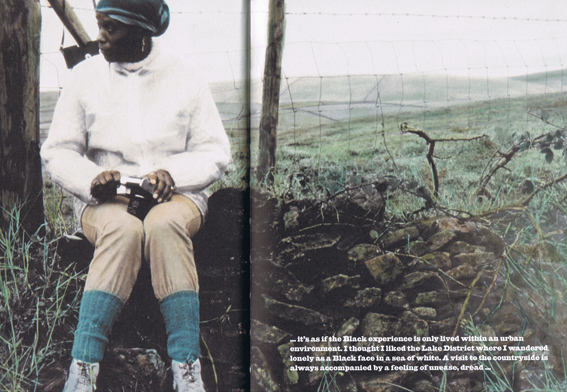

As a Black woman, Pollard articulates in her Pastoral Interlude and Wordsworth Heritage series several levels of alienation and otherness. The landscape of the Lake District, which she sees as epitomizing the ‘authentic’ British countryside, confirms the status of the Black woman as an outsider. For instance, in Pastoral Interlude, Pollard captions a photograph of a lone black female figure in the landscape,

“…it’s as if the Black experience is only lived within an urban environment. I though I liked the Lake District where I wandered lonely as a Black face in a sea of white. A visit to the countryside is always accompanied by a feeling of unease, dread….â€

© Ingrid Pollard

The caption indicates what she takes to be the oppressive homogeneity of visitors to the region. Writing about Pastoral Interlude in her book Postcards Home (Chris Boot Ltd, 2004) Pollard says “There was an unconscious selection of the lone figure within the landscape. It became a way of working. The stylized posed figures, the use of historical details about a particular place. Nothing about the scene is really ‘natural’. It’s as manufactured and deliberate as the assumptions and stereotypes about Black people.â€

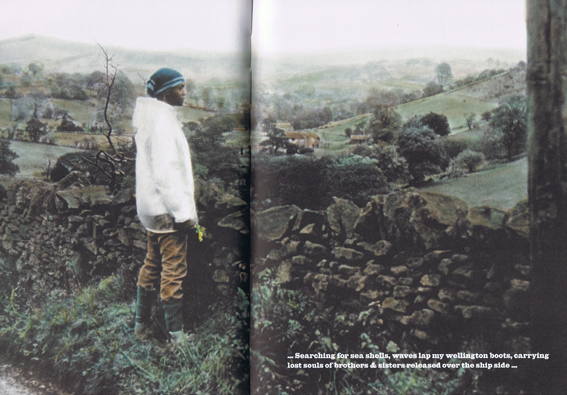

Pollard’s use of surprising, sometimes shocking captions subvert her images which otherwise show someone, who at first glance, looks like they seem to be enjoying themselves in the countryside and appear to be ‘at home’. For instance, another image of herself in the Lake District she captions

“…Searching for sea shells, waves lap my Wellington boots, carrying lost souls of brothers & sisters released over the ship side…â€

© Ingrid Pollard

As John Taylor writes in his book A Dream of England, “despite the commodification of the countryside as a haunt for well-equipped ramblers, following in the footsteps of the Romantics, for Pollard the landscape is disenchanting: the spell it casts as a commodity seeks to discount her as a customer. Her landscapes recall with irony the tradition of eighteenth century British landscape painting, which sought to establish the countryside as the natural domain of the British middle classes.â€

Twenty years after her Pastoral Interlude work was made, I wonder whether Pollard would still find the English countryside as insular and racist as she did then?

Another photographer, whose work has challenged our stereotypes and conventional readings of English rural landscapes would be John Kippin. Kippin’s work pays allegiance to the conventions and traditions of pictorial landscape whilst foregrounding issues within contemporary culture and politics. Note particularly his photograph ‘Prayer Meeting, Windemere’ taken from a body of work called Nostalgia for the Future.

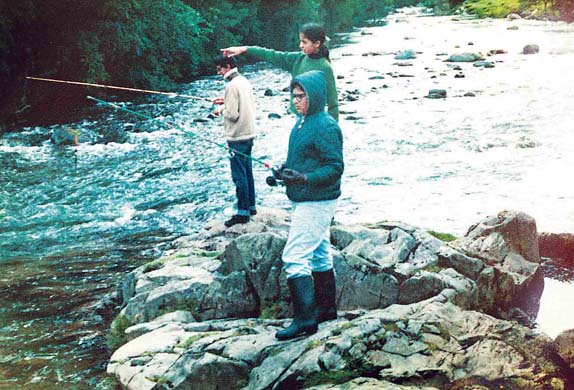

© John Kippin

Describing the scene in Creative Camera (quoted from A Dream of England), Paul Wombell writes that the party are “probably from Lancashire and came to work in the mills, and now they are tourists in this heritage England. It turns the idea of British landscape upside down; who goes there, what meanings can people get†(1992). As Taylor notes “although there is a spiritual tradition to English landscape, prayers in this fashion are quite unconnected to the pantheism or Romanticism which is usually associated with it.â€

This projection of a dominant culture in the countryside can be seen when we look at the preponderance of white, middle-class, middle-aged members of the National Trust (see this article in The Independent).

It was also recently highlighted in a study by the Commission for Racial Equality (2004), which showed that although ethnic minorities make up 8% of the UK population they represented just 1% of visitors to the countryside. The then chairman of the Commission, Trevor Phillips, suggested that a form of “passive apartheid” existed in the British countryside. His comments certainly sparked quite a debate. However, it was interesting to see how many ethnic minorities disagreed with his analysis (see replies posted on the BBC News Online here) and actually felt quite at home in the countryside.

This summer there was an article in The Guardian where four journalists described their memories of holidays in the UK. British born writer Maya Jaggi described her experiences of childhood holidays in the Lake District in the 1970s.

Maya Jaggi, Lake District

“The ingredients of the ideal holiday were fixed for me as a child on a trip to Windermere. After a day on the lake, messing about in a rowing boat with my family, my aunt Madhur gave me a masterclass in boning fish.†She goes on to say “My parents had taken to borrowing a friend’s cottage in the village of Ulpha near Coniston Water. My mother (Madhur’s eldest sister) was head of English in a London school, and was drawn to the Lake poet associations. She would marshal my two older brothers and me to Dove Cottage and Rydal Mount, pointing out the spot where the Ullswater daffodils sprouted. My brothers learned to fish for brown trout in the River Duddon, the inspiration for 34 Wordsworth sonnets (I was keener then on Swallows and Amazons). The riverbanks near Ulpha bridge are now a popular site for picnickers, but we had them much to ourselves.â€

Jaggi makes no reference to her or her family feeling marginalised in the landscape. They seem very much at home. In fact, she goes on to make a connection between the landscape of the Lake District and that of her father’s birthplace of the Punjab-

“For my displaced, cash-strapped parents the Lake District may have been a landscape in which to recreate for us aspects of their own childhoods. My father, whose family lost land in Punjab during Partition, would roll up his trousers and wade gamely into the becks, much to my adolescent embarrassment, while packed lunches on the fells could conceivably stand in for the lavish picnics at Himalayan hill stations that were a mythic part of my mother’s Old Delhi family. After the sisters studied at Delhi University (where my parents met), my mother left for London on her honeymoon, while Madhur, after Rada, settled in Greenwich Village. The English Lakes became a place where a family dispersed across three continents could reassemble.â€

Family pose for a photograph, Bowness-on-Windermere, Lake District © Simon Roberts

In relation to my own journey around England for this project, while I found that much of rural areas in the West Country and Northumbria to be very white, in the Peak District, Yorkshire Dales, North Yorkshire Moors and Lake District I was surprised to witness relatively large numbers of ethnic minorities engaging with the countryside (as Wombell alluded to, this would make sense given the proximity of these rural retreats to large towns and cities with substantial ethnic minority populations, like Burnley, Bradford, Leeds and Blackburn), and seemingly not alienated by the environment.

Climbing the waterfall at Gordale Scar, North Yorkshire © Simon Roberts

Take for example my photograph below of rock climbers on Stanage Edge in the Peak District. In the foreground a Muslim couple wearing distinct grey robes walk on a footpath through the landscape. Our tendency to ‘read’ this view in terms of traditional English activities is hard to resist and the couple therefore seem to be ‘out of place’. On speaking to them I learned that they were from Leicester on a weeks walking holiday, staying at a B&B in the nearby village of Hathersage. They spoke of feeling completely at ease in the area and described how they often spent their holidays exploring the English countryside.

Stanage Edge, Peak District © Simon Roberts

One organization that is trying to engage more ethnic minority groups with rural England is the Mosaic Partnership. Mosaic is an organization forging links between black and minority ethnic community groups across England and Wales with four National Park Authorities (the Peak District, Yorkshire Dales, Brecon Beacons & North York Moors), the Youth Hostels Association (YHA), and the Campaign for National Parks (CNP; formerly the Council for National Parks). They are attempting to promote National Parks as part of our shared cultural heritage, as well as places offering opportunities for physical recreation and spiritual renewal.

You can read accounts written by several ethnic groups who have taken tours in National Parks on Mosaic’s website here.

It’s worth mentioning that there is also a political dimension to landscapes of rural England. Take for example the reporting and politicised nature of the foot-and-mouth outbreak or the trail of Mohammed Hamid, who was jailed in February 2008 for organising al-Qaida style training camps across Britain (read article in The Guardian here). In relation to ethnicity, this latter event is of interest.

Photographs taken by two surveillance officers from Scotland Yard (above) showed Hamid, and several other Muslim men in a group of 23 others, on exercises at a farm in the Elterwater area of the Lake District. In the trial Hamid claimed these were bonding sessions to bring together Muslim men who felt vulnerable after 9/11. But police said he was trying to recruit and train young men for violent jihad. Hamid organised two more camps in the Lakes. The last on 17 August 2004 included 21/7 ringleader Muktar Ibrahim. MI5 officers covertly filmed this gathering. Hamid later organized excercises in secluded sites in the New Forest and paintballing centres in south-east England.

The widespread reporting and publication of these photographs provoked headlines around the world linking rural England with terrorism-

“Training camps for terrorists in UK parks†The Guardian, 14th August 2006

“Holiday trip, or a ‘bomber’ training camp?†Daily Telegraph, 19th January 2007

“Al Qaeda terrorist who took part in Lake District training camp sentenced to six years in prison†Daily Mail, 22nd November 2007

“Network of terrorist camps in rural England – Convictions of 7 militants revealed terror activities in idyllic rural settings†MSNBC, 26th February 2008

“Trial exposes network of UK terror camps” Zee News, 27th February 2008

to be continued….

April 12th, 2012 at 2:30 pm

[…] via We English […]

May 2nd, 2012 at 8:43 am

[…] A wonderful blog on the issue of ethnicity and rurality: http://we-english.co.uk/blog/?p=930 […]

July 26th, 2012 at 1:38 pm

[…] blogger wrote a very interesting commentary of Pollard’s “Pastoral Interlude” photography exhibit from 1987, making us all […]

July 27th, 2012 at 9:26 am

[…] photographer wrote a very interesting commentary of Pollard’s “Pastoral Interlude” photography exhibit from 1987, making us all […]

August 14th, 2012 at 11:27 am

[…] in Britain. She became known for her photographic series questioning social constructs such as Britishness and racial difference. While investigating race, ethnicity and public spaces she has developed a […]