ONE MAN’S LEISURE, ANOTHER MAN’S WORK

August 18th, 2008 adminI’ve just been looking at Nick Rowling’s book The Art Handbook (which seems to be out of print) in which there’s an interesting chapter on the theme of leisure in art.

Here’s his introduction-

“Play and recreation are common to all societies, though the degree to which people can relax and enjoy their leisure various enormously. Sex, class, cultural and age differences also influence the ways in which pleasures can be channeled and permitted in all societies, with the tacit acknowledgement that while the rich have both more time and money to indulge their tastes, the poor are expected to work, and only enjoy themselves in limited ways. The rituals of popular entertainment and the provision of the simplest of toys could nevertheless result in innumerable pleasures as Bruegel’s great painting shows. Furthermore, one person’s leisure is often dependent upon another’s labour, as many of these circus, theatre, marriage and inn scenes make explicit.

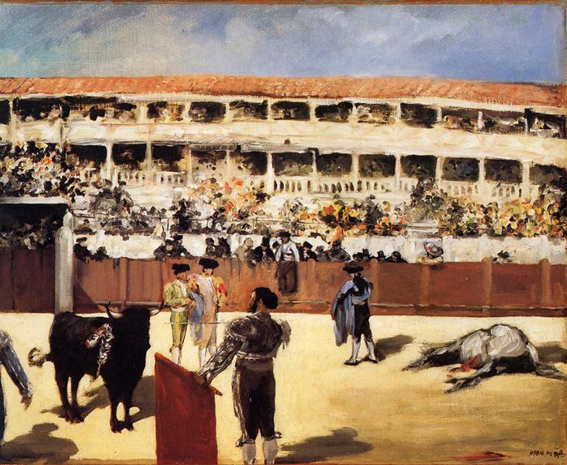

Religious festivals throughout Christian Europe became the focus of communal recreation, as well as being occasions for markets, street entertainments, drinking and love-making. That some of those festivals hark back to the rituals and beliefs of pre-Christian cults is evident from paintings like Goya’s Burial of the Sardine and Manet’s Bullfight. Such festivals were invariably associates with feasting and drinking, and in Flemish and Dutch painting in particular, a moralizing message against drunkenness, lechery and gluttony were clearly intended. Gambling scenes also attracted Flemish and Dutch artists who liked to stress the avarice of crooked gamblers and gullibility of simple-minded punters, and satirists like Rowlandson in the Hazard Room saw gambling in eighteenth-century England as a metaphor of greed itself.

The Burial of the Sardine, Francisco de Goya, 1812-1819, Real Academia De Bellas Artes, Madrid

The Bullfight, Edouard Manet c.1865-67, The Art Institute of Chicago

Naturally, leisure has a context. The different worlds of men and women in bourgeois Europe is particularly marked in painting where women are often depicted alone in their homes, reading, writing, dressing and decorating themselves or perhaps waiting for lovers. The subject of fetes champétre or picnics was popular, not simply because of the possibility it offered of linking a contemporary scene of the delights of landscape, though when Manet, in Déjenuer sur l’herbe, produced a modern version of Giorgione-Titian’s painting, the explicit eroticim of the scene outraged contemporary morality.

Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, Edouard Manet 1863, Musée d’Orsay

Sport too has been popular theme for artists since ancient times: wrestlers, boxers and charioteers decorate innumerable Greek vases, as do hunting scenes and bullfights. Hunting became a courtly pleasure both in medieval Europe and in Mughal India where particular animals were reserved for the dangerous and gubious pleasures of the nobility and where artists were commissioned to record the heroic and bloody exploit of their masters.”

I was interested in his reference to one man’s leisure being another man’s work. This was particularly true of the grouse shooting which I attended last week, where there were as many staff working (game keepers, dog handlers, drivers etc) as there were members of the shooting party.

The head gamekeeper on the shoot (seen in the centre of the photograph) was George Thompson, 52, of Pickering. Mr Thompson has spent the last 17 years nurturing the heather moorland of the 7,000 acre Spaunton Estate (owned by George Wynn-Darley) on the North Yorkshire Moors. After years of working as a scaffolder, he became a gamekeeper in 1991, and was promoted to head moorland keeper at Spaunton in 1999. This year he has been named Gamekeeper of the Year, organised by Farmers Weekly and the Country Landowners Association Game Fair.