WHOSE IDEA?

October 31st, 2008 admin“The subtlest and most pervasive of all influences are those which create and maintain the repertory of stereotypes. We are told about the world before we see it. We imagine most things before we experience them. And those perceptions govern deeply the whole process of perception.â€

Walter Lippman (1987) quoted in The Hollywood Arab

Still no baby yet so I’m going to take this opportunity to respond to a post I received earlier in the summer from a photographer in Italy who challenged my approach to We English. Notably, my decision to invite the general public to post their own ideas which I could then photograph. Here is their post-

Dear Mr Roberts

As a viewer the idea is really functional. As artist the idea it is a bit vicious. Are you playing smart asking people to help?! Finding by yourself events and situations is the main reason to be a photographer. You will be a translator of others ideas and inputs. Are you a politician of a self-thought photographer? And you receive funding as well! Yes definitively you are a bit of a politician.

Giuseppe Mascia, May 3rd 2008

My reply is loosely based on two interviews I did with Joerg Colberg on his blog Conscientious and Jim Casper on Lens Culture in July 2007 where I discussed my approach to Motherland (published: Chris Boot). A number of points I raised are important in helping to answer Giuseppe’s question, and will be fleshed out slightly here.

There were two main reasons for choosing to travel to Russia for my book project, Motherland. Firstly it was somewhere that had always fascinated me. I studied Human Geography at the University of Sheffield and a number of the courses I took looked at social, cultural and economic issues surrounding Russia and the former Soviet Union. Secondly, while there had been a number of important photo documentaries on Russia in the last decade, many were produced around the time of the fall of Communism, and tended to concentrate on themes surrounding disintegration and decay. I felt that the dialogue was very one sided and that the debate had moved on in recent years but photographic representations hadn’t.

ENCOUNTERING ‘THE OTHER’

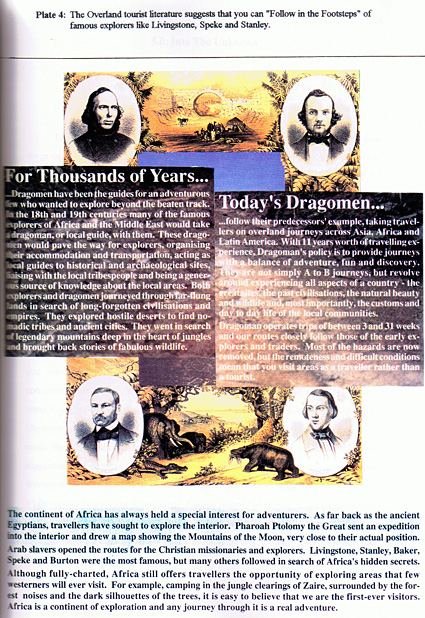

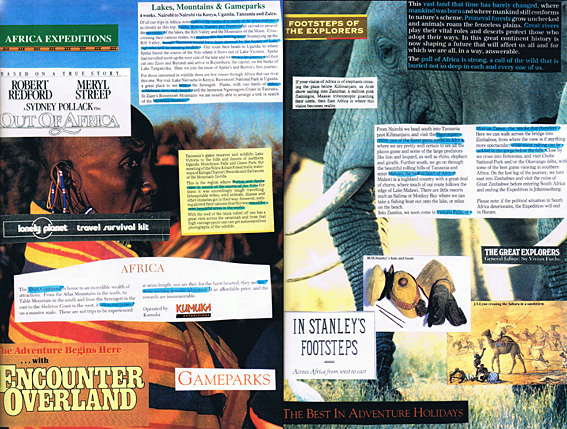

Samples of imagery and text used to advertise British overland tourist trips to East Africa.

The problematic notion of representation and the question of how photographs are important to the construction of senses of place very much informed my approach to Motherland. The context for my approach was based on my BA Hons undergraduate dissertation. Published in 1995, my dissertation, entitled Encountering the Other: Representations and Readings of East Africa, was undertaken while traveling on an overland truck from Kenya to Zimbabwe with a group of Western tourists. Using Edward Said’s concepts of ‘Orientalism’ and ‘imagined landscapes’ my paper looked at Western representations of Africa, in particular those associated with the tourist literature advertising overland expeditions.

Ideas of imagined geographies and representation provide the starting point for Said’s discourse of Orientalism where he attempts to map the production and reproduction of myths and imagined geographies in constructing the inferiority of other people and places. Orientalism maps relationships between Occident and Orient. The Orient, Said argues, is contructed as an object for the Western gaze, a representation of ‘the Other’. Said suggests that although all cultures tend to make representations of foreign cultures, the preponderance of power has been on the side of the self-contituted Western societies.

Tourist literature referencing the English explorers like Livingstone, Stanley and Speke.

The premise of my paper was that as Western tourists our imagery of Africa is one grounded in a colonial history; the 19th century European tradition of the expedition with adventurers such as Livingstone, Park and Thompson going out to explore and encounter distant and exotic lands. These images have been nurtured and re-enforced by the media and tap into a reservoir of ideas we have regarding colonialism, imperialism and representations of far away, exotic places and peoples. These ideas have also been appropriated by modern tourist companies in advertising ‘real’ African experiences; we, the tourist, are branded as adventurous travellers going out to experience the dark heart of Africa.

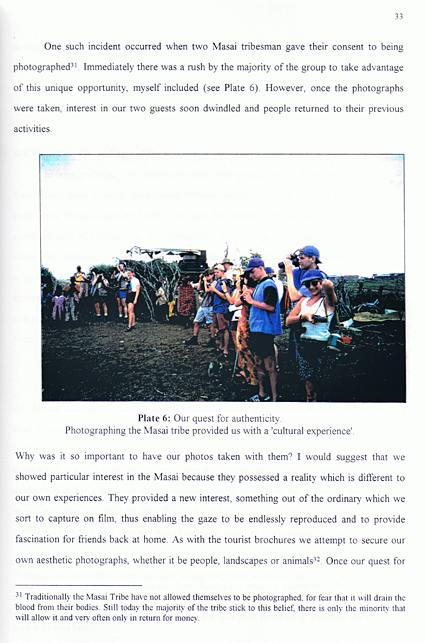

A page reproduced from my dissertation. The photograph is captioned: “Our quest for authenticity- Photographing the Masai tribe provided us with a ‘cultural experience.'”

My research concluded that even once East Africa had been encountered, it was very difficult to overcome the representations of place, engrained stereotypes if you like, that the individuals had brought with them. Evidence of which was presented in the photo albums that people produced at the end of the trip. These albums were representative of the way people remembered and ‘experienced’ East Africa, but the problem remains that many merely reproduced exotic images rather than presenting reconsidered and augmented perceptions of East Africa.

MOTHERLAND

Turning to Russia, I had my own preconceptions of this place. As a child, the Soviet Union seemed vast and mysterious. It took up most of the wall map in my geography classroom and was the vital region to capture to win the board game ‘Risk’. There were the glamorous KGB agents up against James Bond, and the Soviet-bashing propaganda of Cold War films like Red Dawn and Rocky IV. I marvelled at the photographs of Yeltsin aloft a tank outside the White House in Moscow on the collapse of the Soviet Union, ushering in a new but uncertain era.

I’d only been to Russia once before, passing through in 1994 to visit my wife, Sarah, who was studying there. We decided that now would be a fascinating time to return, fifteen years after the fall of Communism. After researching the project for 18 months, we left London in July 2004 and spent the next 12 months travelling over 75,000km from the federation’s Far East, through Siberia to the Northern Caucasus, the Altai Mountains and along the Volga River. We finished in Moscow in July 2005.

Cover of Motherland, published by Chris Boot Ltd, March 2007

The resulting book is meant as a visual statement about the nature of contemporary Russia. It is my attempt to try and move beyond ‘imaginative geographies’ where the fantasies and preconceptions of the photographer are prevalent in the images to a representation of Russia that does not deny the problematic veracity of pictorial representation. Motherland responded to these questions successfully, in my own judgement, for a number of reasons. Firstly, the fact that I spent a continuous year in Russia allowed for a sustained and in depth engagement with the landscapes and people that I came across. While I travelled extensively and did not, as it were, conduct visual ‘fieldwork’ in a single location, the duration of my engagement enabled a spontaneity – I could respond to diverse events and situations, and was neither constrained nor driven by the specific agenda or timeframe of a photojournalistic assignment or news agenda. My preconceptions and expectations about place, for example, were altered the more time I spent there. If, inevitably, a visitor or traveller can only acquire a partial understanding, one that remains ultimately more that of an outsider than an insider, the grasp acquired by a questioning and persistent onlooker will nevertheless be richer and deeper than that of a more transient visitor.

I was constantly conscious about shedding my preconceptions and instead to be led by what I saw and experienced. If I had gone to Russia with the intention of documenting poverty, I would have looked for it – and found it. Instead I wanted to be as open as possible to new ideas and be surprised and challenged by what I found.

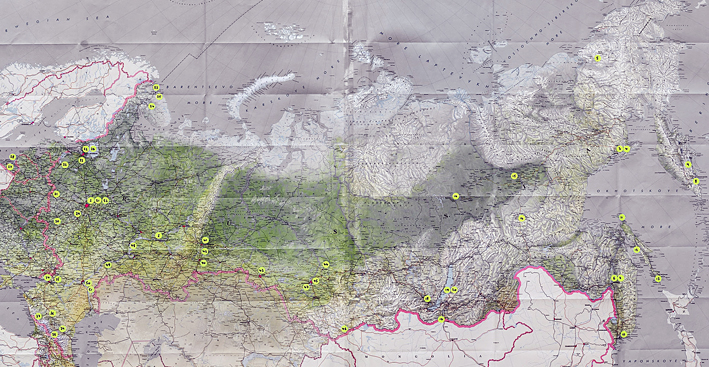

Map of Russia showing where we were each of the 52 weeks of the year.

It was very important that not all of the trip was planned. While I had a framework for the journey, I deliberately left at least half of the itinerary to spontaneity, thereby increasing the chance for my own stereotypes to be challenged and opening up new avenues of exploration that I could otherwise have overlooked. By staying in peoples’ houses, rather than just hotels, I was able to find people and places that I would never have otherwise come across. In some ways enabling me to become an insider rather than just a tourist.

One of the greatest challenges was being able to submerge yourself in some of the larger cities, notably in Siberia, when you often only had a few days. How do you really get a sense of a particular place in a short period of time? You turn up, you book into a hotel, and then how do you integrate yourself into the local society? It’s very difficult. One way I overcame this was by using homestays (sourced from the Hospitality Club website) where I sourced local families to stay with. Instead of just being overwhelmed by a place on arrival, I was immediately experiencing it from a local viewpoint. People introduced me to their friends and took me to places that I would never have found from a guidebook, or from our own research.

In Omsk we stayed with a University professor who gave me a tour of his University and took me to the All Russia Ballroom Dance Contest, which his daughter was competing in (which led to the portrait of Nikita and Rufina); in Rostov-on-Don I stayed with a local journalist who gave me a tour of the Cossack military base (which led to a portrait of a Cossack soldier on horseback); in Yekaterinburg I stayed with Sergei who took me for a banya with his son Kostya (which led to the image of them bathing naked in the lake); while in Kamchatka I spent five days trekking through the wilderness on horseback with Paval and Sasha.

Camping with Sasha and Pavel, Kamchatka, October 2004 © Simon Roberts

Sergei and Kostya after a banya, Yekaterinburg, May 2005 © Simon Roberts

To participate in the everyday rites of Russian life and society, to be an involved guest and a friend, as well as an observer and witness, turned out to be tremendously enlightening. On the other hand, the sheer magnitude of the country and the unusually large distances I covered allowed for a greater sense of conceptual and aesthetic comparison, of visual diversity and the cultivation of knowledge and photographic memory. Distance and time, therefore, ensured a naturally more rounded representation of people and place and a recognition of the complexity of my subject.

It was always my intention to combine both landscapes and portraits in the book. I used landscape photographs to provide panoramic overviews of the country, images that help to provide a sense of context, evoking peoples in their diverse habitats and surroundings. I was interested in making detailed pictures that the viewer could read, like a map, and find different cultural and social references in. Where possible, I tried not to crop out any significant details from the landscape I photographed.

Ballroom dancers, Nikita and Rufina, Omsk, May 2005 © Simon Roberts

Cossack soldier on horseback, Rostov-on-Don, April 2005 © Simon Roberts

These landscapes I countered with portraits that are fixed in a narrow moment of time and space and which take you in to the landscapes and provide a much more intimate experience. Most of my subjects were stopped and photographed in the environments where I came across them. I attempted to select as large a cross-section of people as possible, from all walks of life. The portraits were taken before engaging in conversation with the individual so I could remain as detached as possible and their expression appear deadpan. What becomes of greater importance are the details in the image; the clothes they are wearing and the landscapes they inhabit. The portraits are almost an anthropological study. As formal and static in nature as they are – I still think there is often an intimate connection between myself and the subject.

In producing a balanced portrayal it was important not to gloss over the cracks of modern day Russia. The Chechen Republic is still a profoundly emotive issue in Russian society and it would have been wrong to ignore or ‘sensor’ pictures from this region.. At the same time, I have included two very differing images in the book from Chechnya. While one shows the main outdoor market in Grozny in front of heavily shelled apartment blocks (in some ways a more typical image we’re used to seeing), the second shows a group of well-dressed Chechen women and their children in a part of Grozny that has been reconstructed. The latter is a surprising image in terms of our visual references, which have been dominated by negative photographic imagery. It was important that I showed both sides of the story.

Outdoor market in Grozny flanked by shelled apartment blocks, April 2005 © Simon Roberts

Group of Chechen women, Central Square, Grozny, April 2005 © Simon Roberts

Of course my view is still only a representation of Russia, “a construction that is contingent, partial and unfinished.†Duncan & Ley, 1993 (Place, Culture, Representation pub Routledge) and one which reflects my own set of ideas and biography. However, the book will now stand alongside many other bodies of work about Russia and, hopefully, form part of a wider photographic debate about contemporary Russia.

More recently I decided to create a website for the book and have a guest book page where people can leave comments about the work in a public forum. Here I am most interested in receiving feedback from a wider audience, particularly Russians themselves, where people can discuss how they perceive my representations of Russia.

Screengrab of the guest book page on Motherlandbook.com

WE ENGLISH

Turning to my England project, I won’t discuss much about the background to the work, which you can read on the blog here, instead look at why I decided to request ideas from the general public.

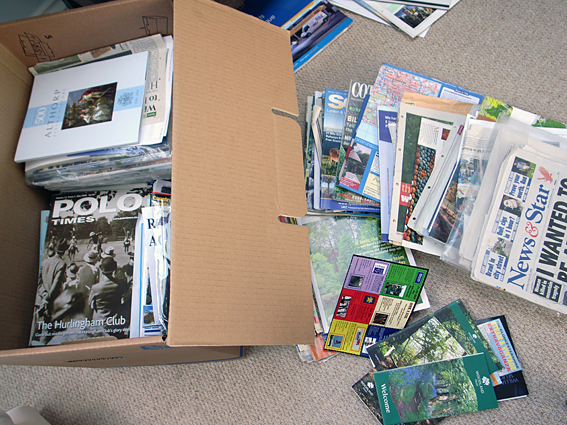

I had plenty of ideas about what I wanted to photograph for this project. Two boxes full in fact. At one point I employed a researcher to help me sift through the piles of cuttings, tourist brochures, books and leaflets I’d amassed. However, this is the point, these were my ideas. My representations of England. What I was interested in also discovering, were other people’s ideas about England; gaining a sense of their perceptions of this place, rather than just photographing my own.

Box of cuttings gathered during research for We English.

In all I received about 250 ideas from the general public. Ideas which, in themselves, provide an interesting snapshot of England in 2008. They illustrate what’s important to people and explore their own ideas on the notion of Englishness. They also enabled me to get a broader spectrum of coverage across themes and geographical locations and helped to find subject matter, especially on the local level, that could otherwise elude me. Rather than just photograph yet another Cheese Rolling Festival, a now cliched tradition, I wanted to find out what else happens in England that may not be part of the national conciousness.

In the end, I only probably used about 10% of the ideas provided. However, I’m considering printing them as an appendix to book, unedited, to sit alongside my own photographic representation of England.

November 2nd, 2008 at 3:59 pm

Hi

Great work … but and this isn’t really on-topic … but a few weeks back you mentioned using a friends epson v750 scanner … I was wondering what your thoughts were on it.. maybe if you have time you could let me know as Im considering getting one.

Thanks

Tom