We’re now in Cumbria and have spent the last couple of days visiting relatives. I’ve always been interested in people’s interior design choices so here are a couple of bathroom interiors at one of my relatives-

Posted in MISCELLANEOUS | Comments Off on INTERIOR DESIGN

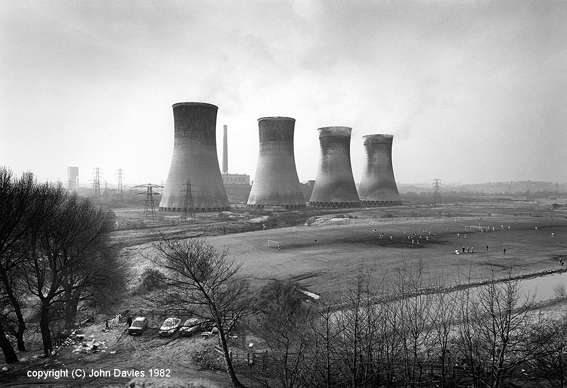

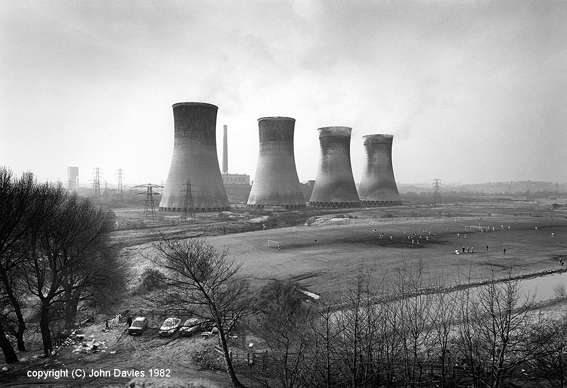

“To view the landscape as a pictorial composition of elements is simplistic. To perceive the landscape within a set of rules (art, science, politics, religion, community, business, industry, sport and leisure) is a way people can deal with the complexity of meanings that are presented in our environment. We are collectively responsible for shaping the landscape we occupy and in turn the landscape shapes us whether we are aware of it or not.” John Davies

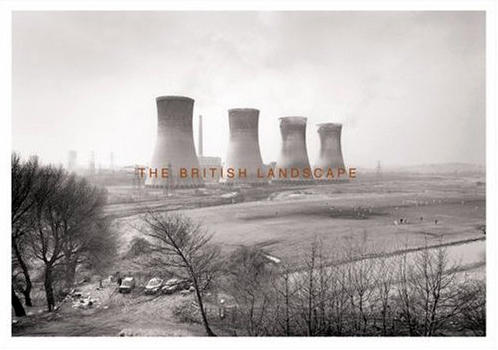

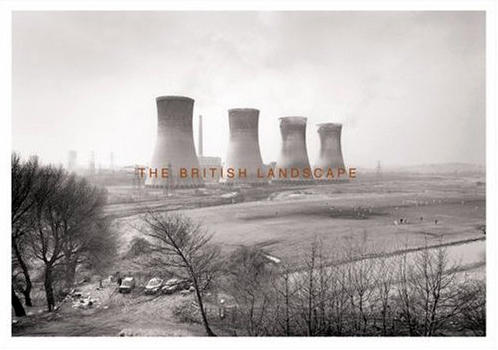

One of the most impressive books published in the last decade by a British photographer looking at Britain is by the celebrated landscape photographer John Davies. The British Landscape (published: Chris Boot Ltd, 2006) features 60 of Davies’ landscape photographs of Britain, made between 1979 and 2005, presented in the order in which they were taken on a large scale with excellent printing reproduction.

I was reminded of Davies’ book while wandering the labyrinth of paths around the North Allotment in Easington Colliery trying to track down Billy Marr’s pigeon lofts. It was here that Davies took one of his celebrated photographs ‘Allotments, Easington Colliery, County Durham’ over twenty years ago. The photograph (reproduced below) shows one of the footpaths through the allotments with a series of old wooden doors used as fences, while in the distance are hundreds of terraced ‘colliery houses’ under a signature moody sky. The photograph is reproduced in his book and was originally taken for an exhibition commission called Durham Coalfield, which was first shown at Side Gallery in Newcastle, 1983.

Allotments, Easington Colliery, County Durham © John Davies, 1983

Easington Colliery began when the pit was sunk in 1899, near the coast. Thousands of workers came to the area from all parts of Britain and with the new community came new shops, pubs, clubs, and rows of terraced colliery houses for the mine workers and their families. The town is known for a mining accident which occurred, on 29 May 1951 when an explosion in the mine resulted in the deaths of 83 men.

The Durham Coalfield exhibition focused on one industry’s effect on the landscape – coal production. Davies concentrated on the comparatively few places in the area (about 70 pits were closed during the 1960s) that were still producing coal – mainly 13 working collieries, the major opencast mines, and to a lesser extent the drift mines and sea-coal gatherers. His photographs, with their combination of general view and finely noted detail, make powerful and visually sensitive documents of the effect on the Durham landscape of two centuries of coal mining.

The allotments had changed little since Davies’ photograph was taken, with the old wooden doors still standing proud. However, the town has changed significantly with the closure of the mine in 1993 and the loss of 1,400 jobs. This caused a massive decline in the local economy; Easington Colliery is currently the 4th most economically deprived place in England.

You can see all his photographs from the commission here.

With reference to We English and my interest in leisure, here are two more of Davies’ photographs, including the iconic image ‘Agecroft Power Station, England, 1982’ which features on the cover of The British Landscape:

and ‘Bowling Greens, Stockport, England, 1988’:

You can read a review of The British Landscape on the blog Photography & Books here.

You can see more of John Davies work on his website here.

Davies’ is represented by Michael Hoppen Gallery in London, and you can read his biography here.

Posted in OTHER STUDIES, PLACES | Comments Off on JOHN DAVIES & EASINGTON COLLIERY

I spent last Friday enjoying a crash course in the sport of pigeon fancying, with the very amiable Billy Marr as my tutor. While thirty of his pigeons were enjoying their daily fly, Billy ran me through his techniques for breeding, training and racing pigeons. Like most pigeon fanciers, Billy was born into the sport. Along with his two brothers he has been breeding and flying pigeons for over 30 years from his loft in the North Allotment in the town of Easington. (A town based around the local colliery, which closed in 1993. It was also where most of Stephen Daldry’s film Billy Elliot was shot).

During a race, all the pigeons start from a transport truck which can be parked up to 200 miles away, but the finish line is each pigeon’s home loft. Each race has a distance, but not all the pigeon’s fly the same distance. The first pigeon to reach its loft isn’t necessarily the winner. The fastest flyer, calculated in yards per minute, wins the race.

Each member has a clock synchronized with the club’s master clock. The distance from each owner’s loft to the start of the race has been surveyed and calculated. Each pigeon wears a registration band on one leg and a rubber band on the other. In the Easington Working Men’s Club that night I watched Billy and his fellow members of the South East Durham Federation synchronize their clocks for tomorrow’s race.Â

The pigeon’s rubber band is the ‘message’ it’s carrying. That message goes into the clock, and the clock marks the time the pigeon returns. The pigeon’s time of return is used to figure the speed of the bird and crown a race winner.

I found it fascinating to witness Billy’s devotion to his pigeons – a species Ken Livingstone famously described as “flying rats”. In the north-east of England, where pigeon racing is still popular enough to support hundreds of local clubs, a handful of wonderfully named federations such as the Up North Combine (which Billy is a member of) and the West Durham Amalgamation and weekly races contested by tens of thousands of pigeons, the tradition and the passion are deeply ingrained.

The sport requires a huge time commitment and for those who want to win, and it is no longer a particularly cheap hobby. Billy feeds them corn that costs over £10 a bag and every bird receives an annual vaccination against paramyxovirus to keep it in peak condition. It costs between 50p and £1 to enter a pigeon in a race, which may be contested by up to 6,000 birds, but the prize money is modest (the winners at a recent national event shared a £4,000 pot). Buying birds for breeding can be expensive, however – the record is £110,000 for a single pigeon  (Invisible Spirit bought byÂ

Young people are not exactly flocking to pigeon racing, and everyone concedes that the sport has been in decline since the glory days of the 1950s. Peter Bryant, general manager of the Royal Pigeon Racing Association, says it loses about 2,000 members a year. “We call it the Sony PlayStation and David Beckham syndrome,” he says. “It’s very difficult to get youngsters into the sport. The old racers are dying and the youngsters aren’t coming through.”

For a comprehensive background to the sport in the UK go to this link.

Â

Posted in EVENTS & PASTIMES | 2 Comments »

My ebony camera proved to be of great interest to a group of (bored and drunk) teenagers I came across on the site of the old colliery in Horden.

Horden Colliery had been one of the biggest mines in the country. From the beginning of construction in 1900 to nationalisation in 1947 it was owned and operated by Horden Collieries Ltd and was operated mainly for the purpose of working undersea coal.

At the height of operating in the 1930s it employed over 4000 men and produced over 1.5million tonnes of coal a year. The colliery thrived until the early 1970’s when water and geological problems occurred.  It finally closed in 1986.

Â

Posted in PLACES | 1 Comment »

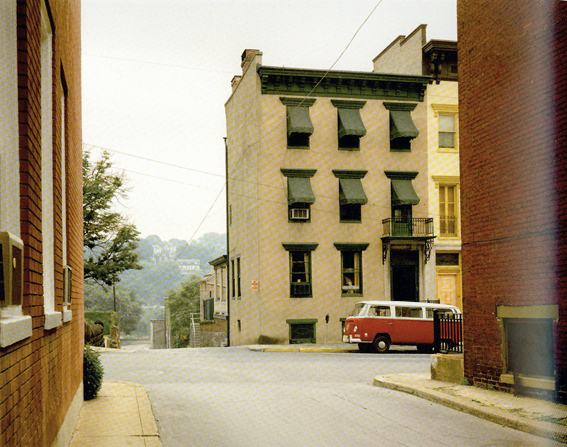

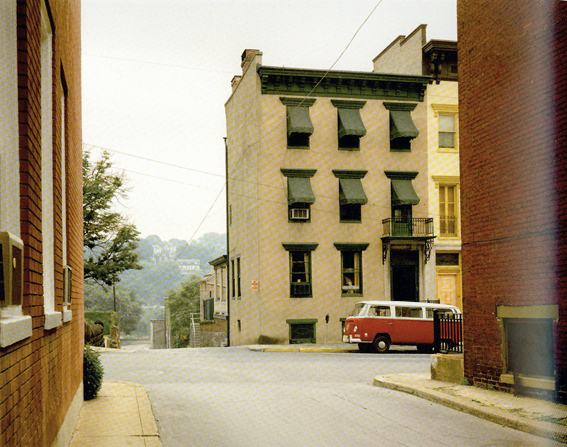

I’ve just come across this interview with Stephen Shore on Darius Himes’ blog while researching another post. It’s very enlightening on Shore’s work (of which much has been written). The answer to the following question particularly resonates and, dare I say it, partly explains what I’m trying to do with the 5×4 in We English!

Darius Himes- Gerry Badger has described your work as an “heroic articulation of the real.†Which to me carries connotations of the work as a support for contemplation. What do you think he means by this?

Stephen Shore- For me it has to do with the view camera. In the original Uncommon Places, there’s a picture of Eason, PA, with a red and white Volkswagen van in it.

I made that photograph on the first day that I used the 8×10; all the work in A Road Trip Journal is made with a 4×5 and then I took one short trip in ‘74 with the 4×5 before borrowing a friends’ 8×10. As you’re looking at the photograph, you realize that there is a boy sitting in the window and that you can even see his breath on the glass. It was this photograph that made me realize that with this camera I don’t have to walk across the street and photograph him. I can let him be a tiny little thing to be discovered in the picture. This was a very different technical approach from American Surfaces, for instance. So that changes the relationship of the viewer to the picture and the function of the picture. It’s not just a window directing your attention–â€here look at thisâ€â€” but is something itself to be the object of attention and to be explored. I think that’s similar to what Badger is saying.

Â

Posted in INSPIRATION | Comments Off on HEROIC ARTICULATION OF THE REAL

There’s an article in today’s Guardian G2 section where four writers have been sent back to the corner of Britain that once gave them so much enjoyment.

Hannah Pool, north Cornwall

Memories-on-Sea features Blake Morrison re-visiting the North Wales coast, Hannah Pool in Cornwall, Stuart Jeffries on the Isle of Wight and Maya Jaggi visiting the Lake District.

Posted in RESEARCH | Comments Off on MEMORIES ON SEA

I’ve just been looking at Nick Rowling’s book The Art Handbook (which seems to be out of print) in which there’s an interesting chapter on the theme of leisure in art.

Here’s his introduction-

“Play and recreation are common to all societies, though the degree to which people can relax and enjoy their leisure various enormously. Sex, class, cultural and age differences also influence the ways in which pleasures can be channeled and permitted in all societies, with the tacit acknowledgement that while the rich have both more time and money to indulge their tastes, the poor are expected to work, and only enjoy themselves in limited ways. The rituals of popular entertainment and the provision of the simplest of toys could nevertheless result in innumerable pleasures as Bruegel’s great painting shows. Furthermore, one person’s leisure is often dependent upon another’s labour, as many of these circus, theatre, marriage and inn scenes make explicit.

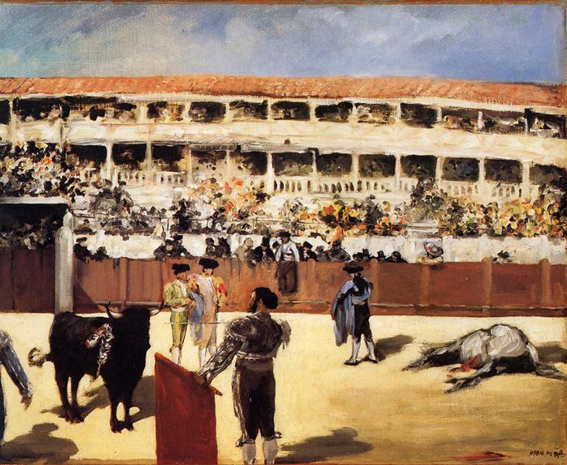

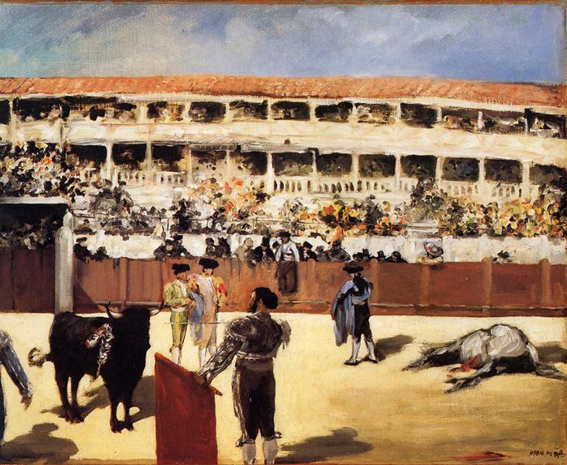

Religious festivals throughout Christian Europe became the focus of communal recreation, as well as being occasions for markets, street entertainments, drinking and love-making. That some of those festivals hark back to the rituals and beliefs of pre-Christian cults is evident from paintings like Goya’s Burial of the Sardine and Manet’s Bullfight. Such festivals were invariably associates with feasting and drinking, and in Flemish and Dutch painting in particular, a moralizing message against drunkenness, lechery and gluttony were clearly intended. Gambling scenes also attracted Flemish and Dutch artists who liked to stress the avarice of crooked gamblers and gullibility of simple-minded punters, and satirists like Rowlandson in the Hazard Room saw gambling in eighteenth-century England as a metaphor of greed itself.

The Burial of the Sardine, Francisco de Goya, 1812-1819, Real Academia De Bellas Artes, Madrid

The Bullfight, Edouard Manet c.1865-67, The Art Institute of Chicago

Naturally, leisure has a context. The different worlds of men and women in bourgeois Europe is particularly marked in painting where women are often depicted alone in their homes, reading, writing, dressing and decorating themselves or perhaps waiting for lovers. The subject of fetes champétre or picnics was popular, not simply because of the possibility it offered of linking a contemporary scene of the delights of landscape, though when Manet, in Déjenuer sur l’herbe, produced a modern version of Giorgione-Titian’s painting, the explicit eroticim of the scene outraged contemporary morality.

Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, Edouard Manet 1863, Musée d’Orsay

Sport too has been popular theme for artists since ancient times: wrestlers, boxers and charioteers decorate innumerable Greek vases, as do hunting scenes and bullfights. Hunting became a courtly pleasure both in medieval Europe and in Mughal India where particular animals were reserved for the dangerous and gubious pleasures of the nobility and where artists were commissioned to record the heroic and bloody exploit of their masters.”

I was interested in his reference to one man’s leisure being another man’s work. This was particularly true of the grouse shooting which I attended last week, where there were as many staff working (game keepers, dog handlers, drivers etc) as there were members of the shooting party.

The head gamekeeper on the shoot (seen in the centre of the photograph) was George Thompson, 52, of Pickering. Mr Thompson has spent the last 17 years nurturing the heather moorland of the 7,000 acre Spaunton Estate (owned by George Wynn-Darley) on the North Yorkshire Moors. After years of working as a scaffolder, he became a gamekeeper in 1991, and was promoted to head moorland keeper at Spaunton in 1999. This year he has been named Gamekeeper of the Year, organised by Farmers Weekly and the Country Landowners Association Game Fair.

Posted in EVENTS & PASTIMES, RESEARCH | Comments Off on ONE MAN’S LEISURE, ANOTHER MAN’S WORK

Continuing my weekly dispatch in The Times, week 12 was taken in Hutton-Le-Hole, North Yorkshire Moors (although, thanks to extended coverage of the Olympics, the picture won’t actually be appearing in the newspaper this week. Back to normal next week).

Hutton-Le-Hole, North Yorkshire Moors, 14th August 2008

A Gun stands in the purple heather on the North Yorkshire Moors during a grouse shoot. August 12 marks the start of the grouse shooting season. From then, until December 10th when the season ends, shooters from all over the world head for the moors of northern England. This party, who were from Dorset, were shooting in the traditional method by walking up grouse over pointers.

This week I’m in Tyneside and Cumbria.

Â

Posted in POSTCARDS | Comments Off on POSTCARD IN THE TIMES- WEEK 12

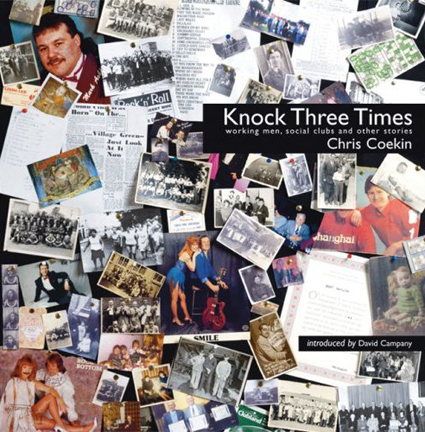

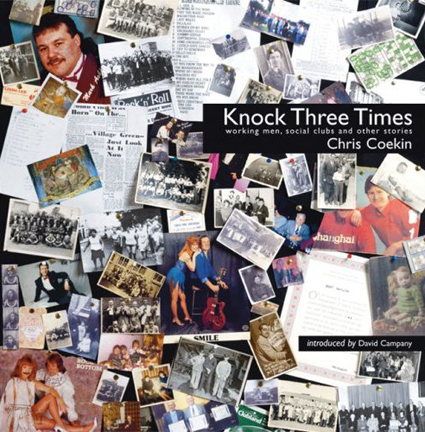

After spending Friday night drinking in the Easington Working Men’s Club I was reminded of Chris Coekin’s fabulous body of work Knock Three Times: Working Men, Social Clubs and Other Stories.Â

Chris’s family has a long tradition of socialising in Working Men’s Clubs. As a child Chris was taken to many clubs in his hometown of Leicester and during family holidays around England. Many of these clubs have long since disappeared. Working Men’s Clubs were originally set up for the support and education of the working man. Knock Three Times is set in the Acomb WMC York where Chris first photographed in 1996. The club, and its members, symbolise the working class community at large.Â

“Using metaphorically driven images and archive ephemera, Chris explores his cultural roots and identity. The vivid, ambiguous, and often autobiographical images reflect his recollections of visiting WMCs as a child. They interrogate the complexities associated with growing up within a working class culture, ideas of masculinity, relationships and its work ethic. The notion of ‘common sense’ provides the foundation for a narrative that looks beyond the surface appearance of WMCs.” As quoted on Chris’ profile page of the University College for the Creative Arts in Rochester, where he lectures.

You can see a slideshow of the work see showcase of the work here and read a review on Jörg Colberg’s weblog here.

Â

Posted in MISCELLANEOUS | Comments Off on KNOCK THREE TIMES

During a visit to Middlesbrough last week I came across six pubs in one day that were either boarded up or had ‘for sale’/ ‘pub to let’ signs up outside, such as the Brambles Farm on Cargo Fleet Lane.

While there are approximately 57,500 public houses in the UK with one in almost every city, town and village, statistics compiled by the British Beer and Pubs Association found that 27 pubs a week closed in 2007 – seven times faster than the previous year and 14 times faster than 2005. This means that four a day are closing in a country where the pub has been an integral part – some might say essential part – of social, cultural and business life for centuries. (Follow this link for a short history of the pub).

In many places, especially in villages, a pub can be the focal point of the community, playing a complementary role to the local church in this respect. The writings of Samuel Pepys describe the pub as the heart of England and the church as its soul.

So why are pubs in trouble? Publicans and landlords talk about rising rent, rates, fuel, property, taxation, lower disposable income (thanks to higher household bills and mortgages), the smoking ban, the trend towards wine drinking, and fierce competition from off-licences, newsagents and supermarkets. Pubs have also suffered from the abundance of alternative leisure pursuits available these days – fifty years ago the choice would have been the cinema, dance hall or a few sporting events. However, somewhat surprisingly given the almost daily headlines of the British binge drinking culture, as a nation we’re actually drinking less. According to the BBPA, average consumption is down 15 per cent on 2000.

One place where I didn’t find much evidence of a slow-down in drinking was Easington Working Men’s Club in Easington Colliery, County Durham, where we enjoyed a pint on Friday night. The place was packed with a full house for bingo and quiz night.

Â

Posted in MISCELLANEOUS | Comments Off on LAST ORDERS