Another photographer whose work has explored the notion of politicised landscapes is John Darwell in his book, Dark Days (Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2007), which documents the 2001 UK Foot and Mouth Epidemic in the Lake District.

Here Darwell explains the work:

“This work produced around my home on the north side of the English Lake District looks at the Foot and Mouth epidemic that swept through the UK in 2001 and became one of the most devastating and significant events to affect the British countryside within living memory, the aftershock of which will continue to shape the future of the countryside for decades to come. The images look to all affected areas from the Lake District fells closed to walkers to the measures farmers went to in order to keep people away from their farms for fear of infection, to the destruction of millions of farm animals and onto the now notorious pyres. The work then continues by recording the extraordinary efforts undertaken by farmers to eradicate the virus from their buildings; and finally the third part of the work looks at the aftermath of the disease and the gradual reopening of the countryside whilst asking questions about the future of the agricultural economy as more and more farms were put up for sale.”

And here are a selection of the photographs:

Dead lambs by roadside © John Darwell, 2001

Roadside pyre © John Darwell, 2001

Barricaded farm entrance, Southwaite © John Darwell, 2001

Farm gate protest sign reads ‘1 of Blairs Killing Fields’, Lorton © John Darwell, 2001

Disinfection bowl, Near Carlisle © John Darwell, 2001

Disinfection mat on the A6, Shap © John Darwell, 2001

Closed picnic site on M6, Carlisle © John Darwell, 2001

Smoke on road, Welton © John Darwell, 2001

Footpath sign closed, Carlisle © John Darwell, 2001

Bangladeshi schoolteachers disinfecting their feet © John Darwell, 2001

Explaining this last picture Darwell comments “this photograph was taken on the first day the fells were open after the lifting of some the access restrictions. I went up Kirkstone Pass to see what was happening. There were dozens of people prepared to go through disinfection to get onto the fells, mostly runners and keen walkers. Whilst I was watching a coach arrived and dozens of people got off, the ladies in saris and sandals the men in linen suits. They had just arrived from Bangladesh and were on their way to Ambleside to begin teaching at the college there. The coach driver being either a comedian or not quite on the ball suggested a nice walk on the hills to get a sense of the place, hence their first experience of Cumbria was having to place their feet in buckets of disinfectant before walking up a soggy hillside. I had a long chat with some of them and after some initial bemusement most seemed to find it quite funny and an experience to take away with them.”

You can see more images from Dark Days on Darwell’s website here.

A book of Dark Days containing 150 colour images plus text pieces by Liz Wells, Professor Roger Breeze, U.S. government advisor on animal epidemics and viral warfare and Alison Nordstrom, Curator of Photographs, George Eastman House, was published in March 2007 (Dewi Lewis Publishing). It is one of the most complete body of images produced during this period and stands as a testament to those ordinary people caught up in extraordinary events (and political incompetence!). It is a work that asks a number of searching questions, either explicitly or implicitly, about the future direction of food production and of the countryside we wish to visit.

Posted in LANDSCAPE, OTHER STUDIES | Comments Off on DARK DAYS

Following on from Friday’s post Contested Countryside, Cumbria-based photographer Stuart Parker got in touch regarding a project he worked on in response to the trial of Mohammed Hamid. Here he explains the reasons behind ‘Tomorrow We Enter Paradise’ along with a few of the photographs from the project.

“As a photographer Iiving in Cumbria I have an interest in social issues in a landscape context, particularly in the Lake District. The idea for this project stemmed from encountering a group of young Asian men on an early morning walk near Buttermere. It later transpired in the news that so called ‘Jihad training camps’ were being monitored in the Lake District by MI5, which reminded me of the group that I had seen.

I decided to explore the places at which the camps had allegedly been held including Wasdale, Buttermere, Grizedale Forest and the Langdale Valley, the latter being where the MI5 surveillance photographs were taken. The result was a series of photographs drawing on actual and metaphorical links between the Lake District, London and Afghanistan. ”

Buttermere © Stuart Parker

Elterwater © Stuart Parker

Buttermere Cone © Stuart Parker

Campfire © Stuart Parker

Langdale © Stuart Parker

Buttermere Church © Stuart Parker

Little Langdale © Stuart Parker

Limbs © Stuart Parker

Tunnel © Stuart Parker

Posted in LANDSCAPE, OTHER STUDIES | Comments Off on TOMORROW WE ENTER PARADISE

I notice that Jem Southam has an exhibition currently showing at The Lowry until the 22nd March 2009. Clouds Descending is the result of a two year commission where Southam made photographs along the Cumbrian coastline, recording the industrial landscape and harbour towns, which Lowry loved so much.

Southam will be giving an evening lecture at The Lowry on February 6th. There is also the opportunity to take part in an all-day Masterclass with him on Saturday 7th February – full application details are available from redeyesubmissions@googlemail.com

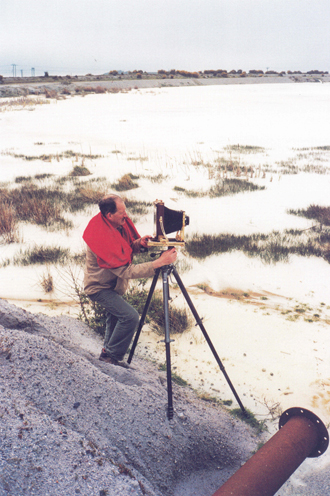

Southam has been a key figure in British photography for over twenty-five years. Working exclusively in the landscape genre, his prevailing thematic concerns are the changes, large and small, occurring within the British countryside. His photographs are the result of patient observation and contemplation over long periods of time. Often producing series, Southam layers and juxtaposes images that not only reveal cycles of nature, but the interactions of humans with their environment. He has said that he proposes “histories,†both social and natural.

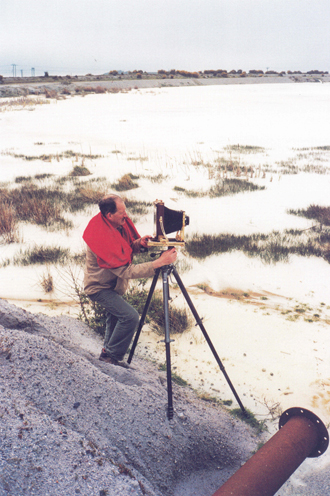

Brampford Speke, 1998 from the series Dew Ponds © Jem Southam

As David Evan’s writes in Source magazine, “For his epic theme, Southam adopts appropriate, time-consuming working methods. There is extensive preparatory research, including the study of weather forecasts. There is walking and waiting, frequently on difficult terrain. Bulky equipment is often being carried around, especially a Wista, a modern Japanese version of a Victorian plate camera. Southam only photographs on still grey days, sometimes producing just a few images in a year. The end results are crafted objects, recalling the work of 19th Century pioneers like Carleton Watkins who took along a wagon laboratory pulled by a dozen mules… Southam’s achievement is to create work informed by past and present that has conviction… [He is] the photographer of the slow rhythms of social time and the even slower rhythms of physical geography.â€

To find out more about Southam’s work, read an interview in SeeSaw Magazine here and watch a slideshow of his photographs here.

Southam is represented by Robert Mann Gallery and Charles Isaacs.

Posted in INSPIRATION, LANDSCAPE, OTHER STUDIES | 1 Comment »

Just before Christmas I attended a talk by Ingrid Pollard at Tate Britain as part of their Conversation Pieces series. It got me thing about my previous post talking about landscapes as contested places and I thought it would be interesting to touch upon the visual relationship between rural England, notions of Englishness and ethnicity.

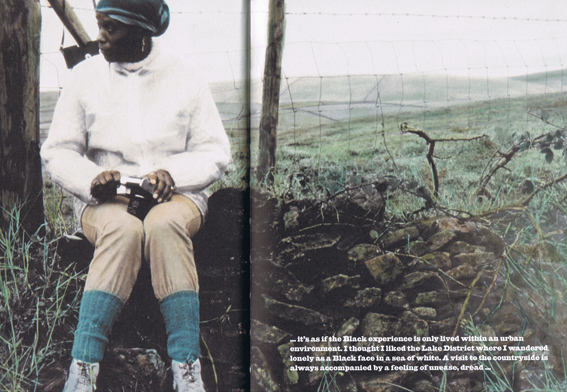

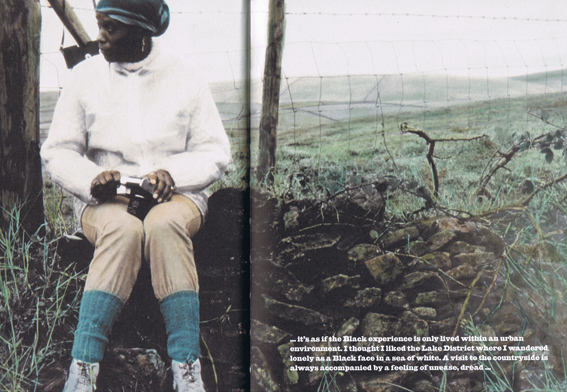

Pollard first came to public attention in 1987 with Pastoral Interlude, a series of photographs about Black people’s experience of the English countryside, particularly the Lake District. Steeped in the heritage of Wordsworth and the Romantic poets, her photographs explore the beauty of the English landscape and coastline, alongside the memories hidden within England’s history and its relationship to Africa and the Caribbean. Her interest in the layers of history is echoed in her use of 19th century photographic techniques.

As a Black woman, Pollard articulates in her Pastoral Interlude and Wordsworth Heritage series several levels of alienation and otherness. The landscape of the Lake District, which she sees as epitomizing the ‘authentic’ British countryside, confirms the status of the Black woman as an outsider. For instance, in Pastoral Interlude, Pollard captions a photograph of a lone black female figure in the landscape,

“…it’s as if the Black experience is only lived within an urban environment. I though I liked the Lake District where I wandered lonely as a Black face in a sea of white. A visit to the countryside is always accompanied by a feeling of unease, dread….â€

© Ingrid Pollard

The caption indicates what she takes to be the oppressive homogeneity of visitors to the region. Writing about Pastoral Interlude in her book Postcards Home (Chris Boot Ltd, 2004) Pollard says “There was an unconscious selection of the lone figure within the landscape. It became a way of working. The stylized posed figures, the use of historical details about a particular place. Nothing about the scene is really ‘natural’. It’s as manufactured and deliberate as the assumptions and stereotypes about Black people.â€

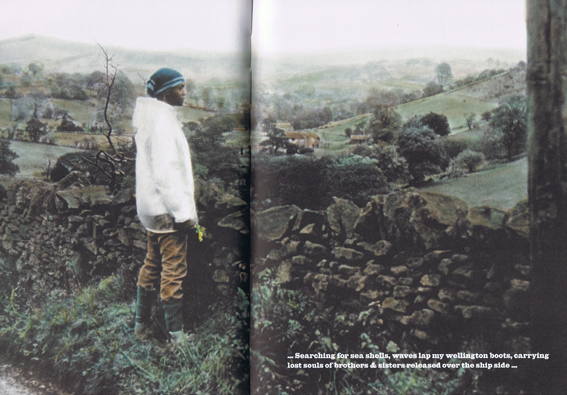

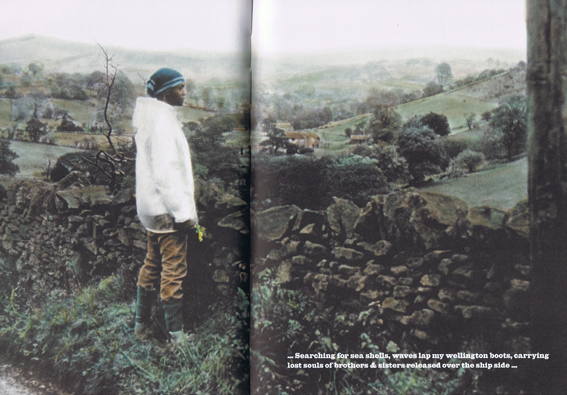

Pollard’s use of surprising, sometimes shocking captions subvert her images which otherwise show someone, who at first glance, looks like they seem to be enjoying themselves in the countryside and appear to be ‘at home’. For instance, another image of herself in the Lake District she captions

“…Searching for sea shells, waves lap my Wellington boots, carrying lost souls of brothers & sisters released over the ship side…â€

© Ingrid Pollard

As John Taylor writes in his book A Dream of England, “despite the commodification of the countryside as a haunt for well-equipped ramblers, following in the footsteps of the Romantics, for Pollard the landscape is disenchanting: the spell it casts as a commodity seeks to discount her as a customer. Her landscapes recall with irony the tradition of eighteenth century British landscape painting, which sought to establish the countryside as the natural domain of the British middle classes.â€

Twenty years after her Pastoral Interlude work was made, I wonder whether Pollard would still find the English countryside as insular and racist as she did then?

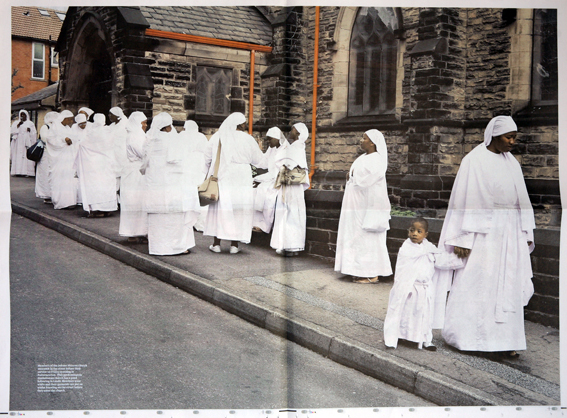

Another photographer, whose work has challenged our stereotypes and conventional readings of English rural landscapes would be John Kippin. Kippin’s work pays allegiance to the conventions and traditions of pictorial landscape whilst foregrounding issues within contemporary culture and politics. Note particularly his photograph ‘Prayer Meeting, Windemere’ taken from a body of work called Nostalgia for the Future.

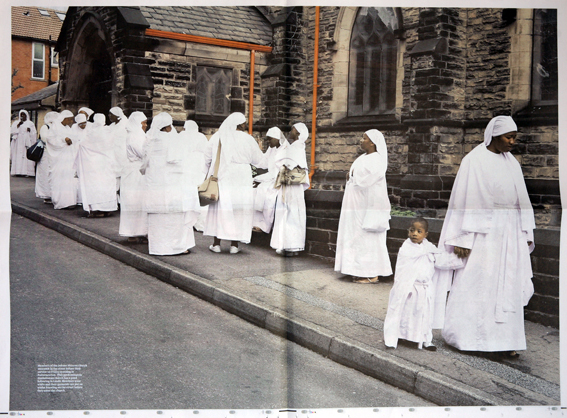

© John Kippin

Describing the scene in Creative Camera (quoted from A Dream of England), Paul Wombell writes that the party are “probably from Lancashire and came to work in the mills, and now they are tourists in this heritage England. It turns the idea of British landscape upside down; who goes there, what meanings can people get†(1992). As Taylor notes “although there is a spiritual tradition to English landscape, prayers in this fashion are quite unconnected to the pantheism or Romanticism which is usually associated with it.â€

This projection of a dominant culture in the countryside can be seen when we look at the preponderance of white, middle-class, middle-aged members of the National Trust (see this article in The Independent).

It was also recently highlighted in a study by the Commission for Racial Equality (2004), which showed that although ethnic minorities make up 8% of the UK population they represented just 1% of visitors to the countryside. The then chairman of the Commission, Trevor Phillips, suggested that a form of “passive apartheid” existed in the British countryside. His comments certainly sparked quite a debate. However, it was interesting to see how many ethnic minorities disagreed with his analysis (see replies posted on the BBC News Online here) and actually felt quite at home in the countryside.

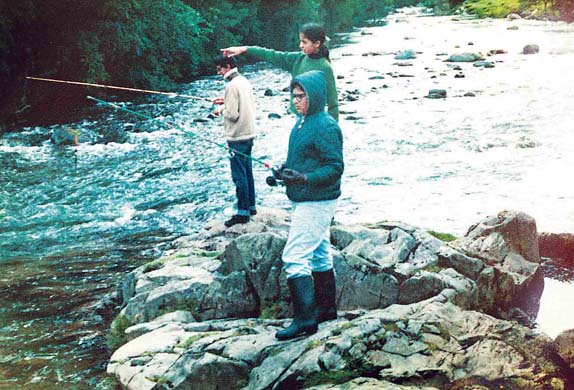

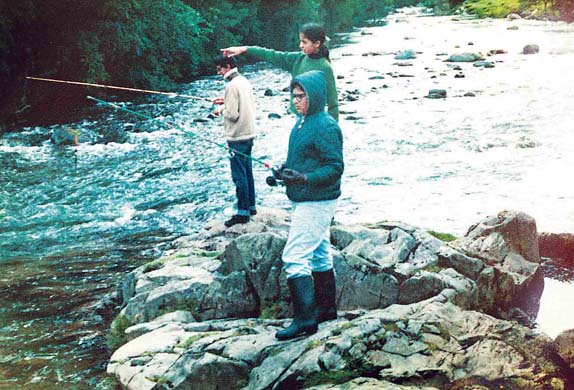

This summer there was an article in The Guardian where four journalists described their memories of holidays in the UK. British born writer Maya Jaggi described her experiences of childhood holidays in the Lake District in the 1970s.

Maya Jaggi, Lake District

“The ingredients of the ideal holiday were fixed for me as a child on a trip to Windermere. After a day on the lake, messing about in a rowing boat with my family, my aunt Madhur gave me a masterclass in boning fish.†She goes on to say “My parents had taken to borrowing a friend’s cottage in the village of Ulpha near Coniston Water. My mother (Madhur’s eldest sister) was head of English in a London school, and was drawn to the Lake poet associations. She would marshal my two older brothers and me to Dove Cottage and Rydal Mount, pointing out the spot where the Ullswater daffodils sprouted. My brothers learned to fish for brown trout in the River Duddon, the inspiration for 34 Wordsworth sonnets (I was keener then on Swallows and Amazons). The riverbanks near Ulpha bridge are now a popular site for picnickers, but we had them much to ourselves.â€

Jaggi makes no reference to her or her family feeling marginalised in the landscape. They seem very much at home. In fact, she goes on to make a connection between the landscape of the Lake District and that of her father’s birthplace of the Punjab-

“For my displaced, cash-strapped parents the Lake District may have been a landscape in which to recreate for us aspects of their own childhoods. My father, whose family lost land in Punjab during Partition, would roll up his trousers and wade gamely into the becks, much to my adolescent embarrassment, while packed lunches on the fells could conceivably stand in for the lavish picnics at Himalayan hill stations that were a mythic part of my mother’s Old Delhi family. After the sisters studied at Delhi University (where my parents met), my mother left for London on her honeymoon, while Madhur, after Rada, settled in Greenwich Village. The English Lakes became a place where a family dispersed across three continents could reassemble.â€

Family pose for a photograph, Bowness-on-Windermere, Lake District © Simon Roberts

In relation to my own journey around England for this project, while I found that much of rural areas in the West Country and Northumbria to be very white, in the Peak District, Yorkshire Dales, North Yorkshire Moors and Lake District I was surprised to witness relatively large numbers of ethnic minorities engaging with the countryside (as Wombell alluded to, this would make sense given the proximity of these rural retreats to large towns and cities with substantial ethnic minority populations, like Burnley, Bradford, Leeds and Blackburn), and seemingly not alienated by the environment.

Climbing the waterfall at Gordale Scar, North Yorkshire © Simon Roberts

Take for example my photograph below of rock climbers on Stanage Edge in the Peak District. In the foreground a Muslim couple wearing distinct grey robes walk on a footpath through the landscape. Our tendency to ‘read’ this view in terms of traditional English activities is hard to resist and the couple therefore seem to be ‘out of place’. On speaking to them I learned that they were from Leicester on a weeks walking holiday, staying at a B&B in the nearby village of Hathersage. They spoke of feeling completely at ease in the area and described how they often spent their holidays exploring the English countryside.

Stanage Edge, Peak District © Simon Roberts

One organization that is trying to engage more ethnic minority groups with rural England is the Mosaic Partnership. Mosaic is an organization forging links between black and minority ethnic community groups across England and Wales with four National Park Authorities (the Peak District, Yorkshire Dales, Brecon Beacons & North York Moors), the Youth Hostels Association (YHA), and the Campaign for National Parks (CNP; formerly the Council for National Parks). They are attempting to promote National Parks as part of our shared cultural heritage, as well as places offering opportunities for physical recreation and spiritual renewal.

You can read accounts written by several ethnic groups who have taken tours in National Parks on Mosaic’s website here.

It’s worth mentioning that there is also a political dimension to landscapes of rural England. Take for example the reporting and politicised nature of the foot-and-mouth outbreak or the trail of Mohammed Hamid, who was jailed in February 2008 for organising al-Qaida style training camps across Britain (read article in The Guardian here). In relation to ethnicity, this latter event is of interest.

Photographs taken by two surveillance officers from Scotland Yard (above) showed Hamid, and several other Muslim men in a group of 23 others, on exercises at a farm in the Elterwater area of the Lake District. In the trial Hamid claimed these were bonding sessions to bring together Muslim men who felt vulnerable after 9/11. But police said he was trying to recruit and train young men for violent jihad. Hamid organised two more camps in the Lakes. The last on 17 August 2004 included 21/7 ringleader Muktar Ibrahim. MI5 officers covertly filmed this gathering. Hamid later organized excercises in secluded sites in the New Forest and paintballing centres in south-east England.

The widespread reporting and publication of these photographs provoked headlines around the world linking rural England with terrorism-

“Training camps for terrorists in UK parks†The Guardian, 14th August 2006

“Holiday trip, or a ‘bomber’ training camp?†Daily Telegraph, 19th January 2007

“Al Qaeda terrorist who took part in Lake District training camp sentenced to six years in prison†Daily Mail, 22nd November 2007

“Network of terrorist camps in rural England – Convictions of 7 militants revealed terror activities in idyllic rural settings†MSNBC, 26th February 2008

“Trial exposes network of UK terror camps” Zee News, 27th February 2008

to be continued….

Posted in OTHER STUDIES, REPRESENTATION, RESEARCH | 5 Comments »

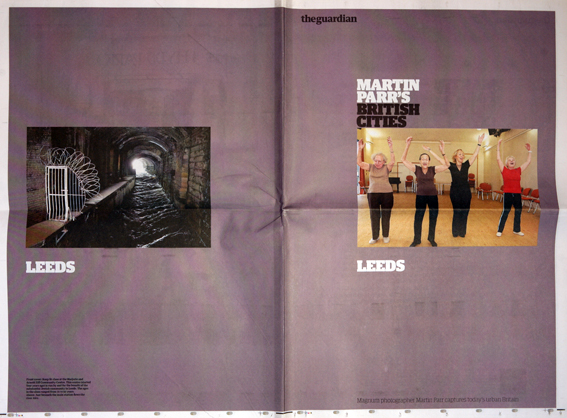

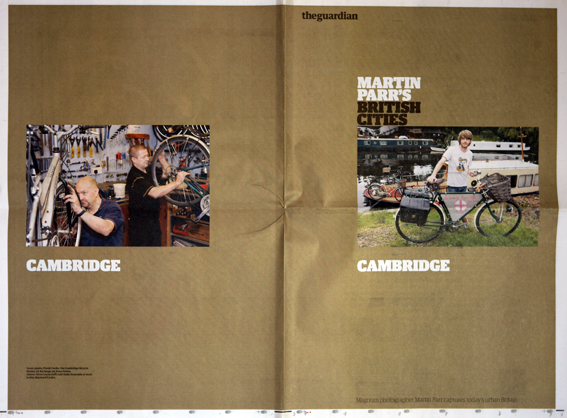

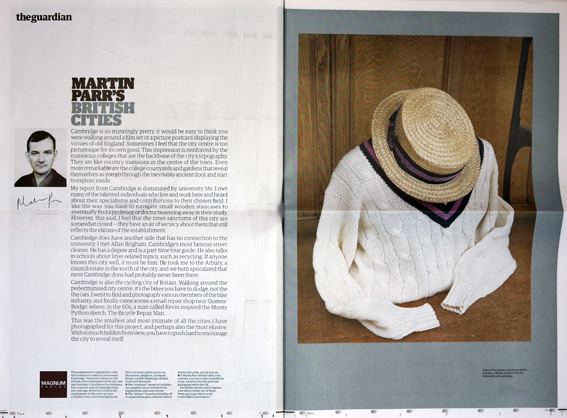

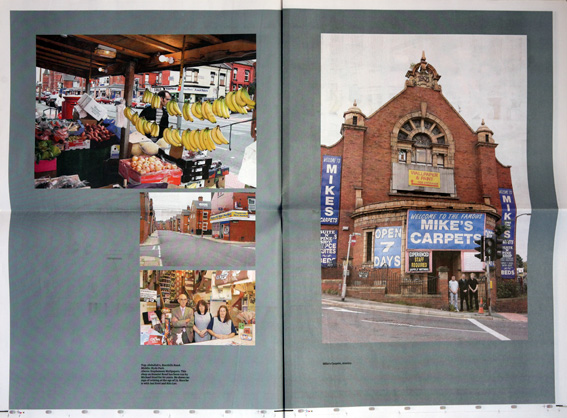

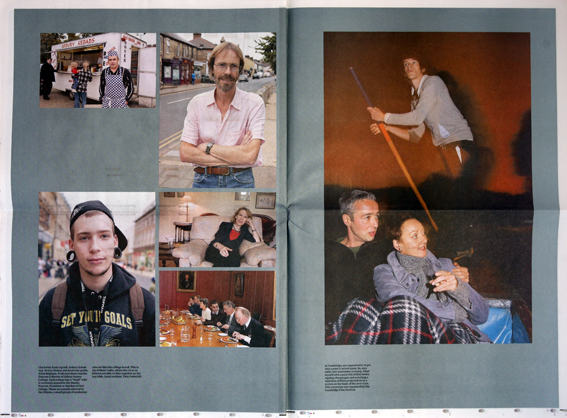

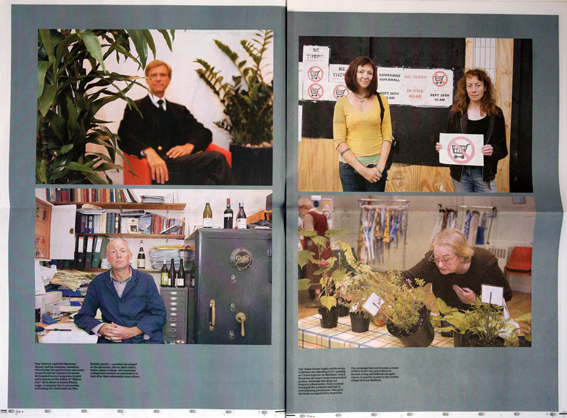

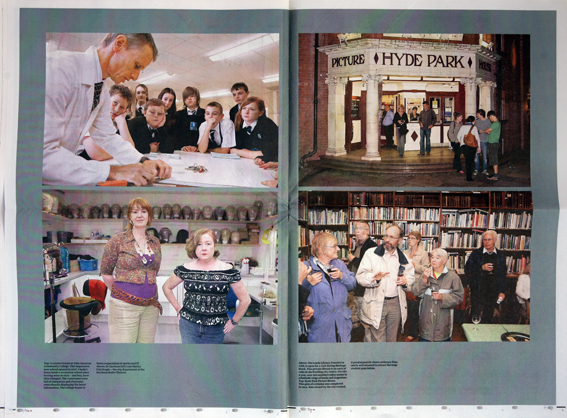

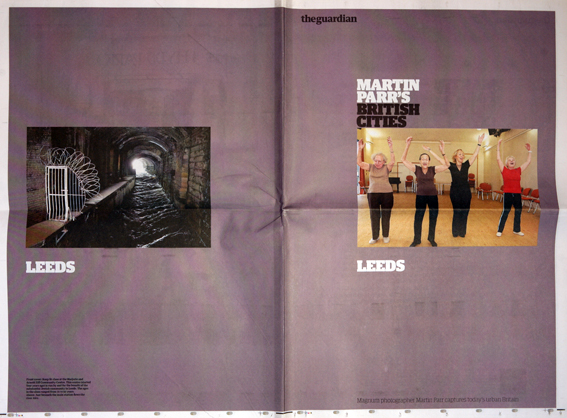

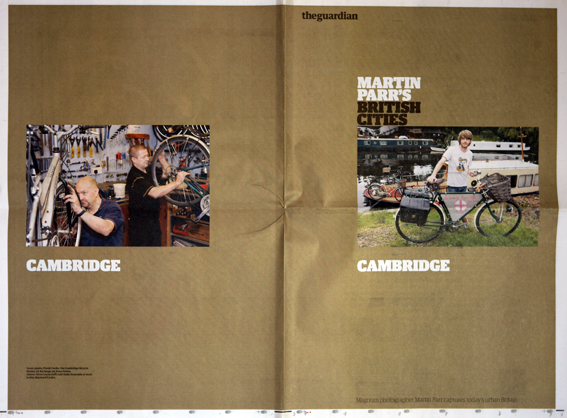

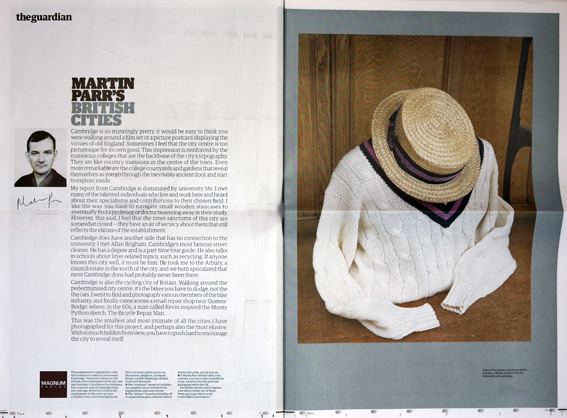

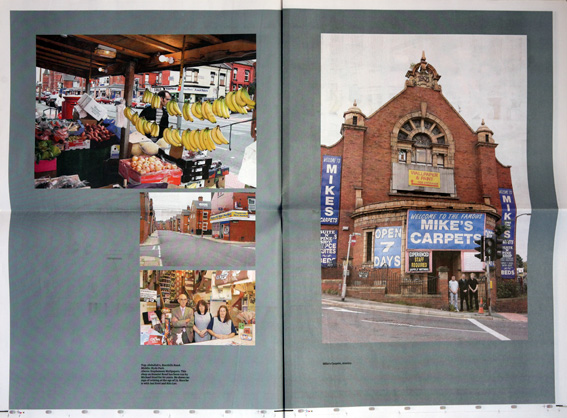

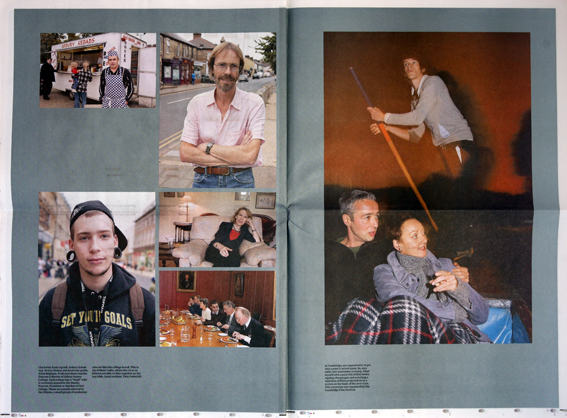

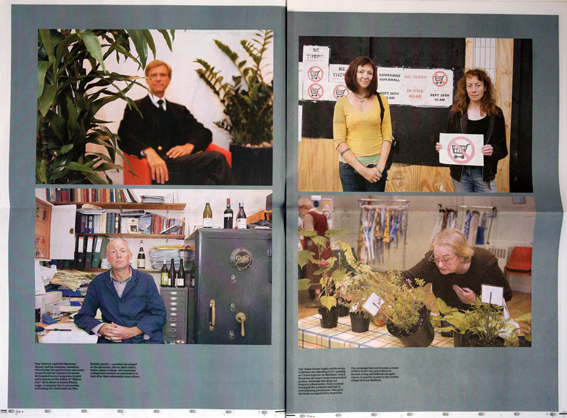

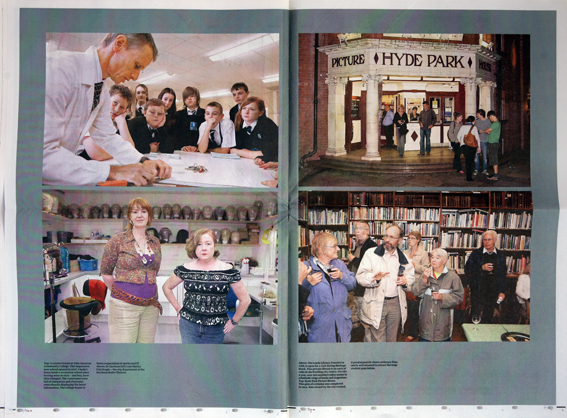

Martin Parr got in touch after my post commenting on photographs from his British cities project (Underwhelmed by Parr), which published in The Guardian’s Weekend Magazine. Martin was kind enough to send me a couple of samples of the individual supplements, so I thought I’d post up some layouts along with quotes from him talking about the work. (Quotes were taken from an interview Martin did with David Land in the RPS Journal, October 2008 issue, and on the Martin Parr We Love U/Discuss? Flickr page).

As readers will know from my post, I was quite critical about the photographs that featured in The Guardian. Martin replied-

“Do remember Simon has only seen the spread in the Weekend magazine, which I did not think was the best edit. Had this been the only thing someone had seen I would have sympathy with his comments. I did relinquish control for the Weekend spread, but was given the chance to sign off and indeed steer the individual supplements in the direction I wanted. Any criticism should be based on the original edit, that I signed off. There have been many comments on this project, some negative and some critical. However if you look at all 160 pages of my depiction of contemporary Britain, it does make sense.â€

“The motivation for the Guardian was very simple, they wanted to find a project that helped to boost circulation (or at least on the day of publication) in their key cities for readership (London being the exception). This is why Cambridge had a supplement, and Birmingham did not. They also wanted to demonstrate that they are interested in the key regional cities in the UK.”

The cities and publication dates for the supplements were-

Cardiff (July 26th 2008)

Bristol (Aug 2nd 2008)

Edinburgh (Aug 23rd 2008)

Belfast (Sept 27th 2008)

Newcastle and Cambridge (Oct 25th 2008)

Leeds (Nov 22nd2008)

“That said I believe the boldness of this project has to be applauded as they have shown real commitment to photography by commissioning this. All the images from this project will potentially go towards a new book I am planning about the UK in a few years time. The Guardian were keen to make a book, and I steered them away from this, as I thought the idea of a box of the original newspaper supplements was a lot better. I still do, as this project has an identity that is unique.â€

“It’s been fantastic doing this project on British cities, because its given me a chance to go round and meet remarkable individuals, shops that are hanging on, fighting against the big chains, I do of course go into the supermarkets, but I try and find shops that have real character, where the individual owner or managers is flourishing, so I can show both sides of what’s happening. The great thing about doing this project is that it give me a chance to plug and talk positively about these small retailers. Even in a city that you think you know, you might not know about them, so it’s a small contribution to trying to make people aware of some of the pleasures and joys that the city may contain.â€

“Many people have criticised my portraits as they did not fit into their agenda. I remind people that when one is a photographer, you have the right to have an agenda, and thank God that is the case. Without them any documentary work becomes very tedious. Why would I expect this to overlap with mine?â€

“I had no agenda apart from looking round, finding photogenic situations and I believe that I am entitled to shoot what i like.”

“My palette and my work is changing and shifting constantly. It would be too easy to repeat the language that I used in the 1980s in The Last Resort. Now I’m shooting predominantly digital, so it immediately gives me a different palette. Whereas in the past I shot on highly saturated amateur film emulsions, as part of the language I’d built up, now I shoot on a Canon EOS 5D with a ring flash, although the thing I really swear by is my Gary Fong diffuser.â€

David Land sums up his interview in the RPS Journal: “You might not immediately recognize Parr’s recent work as being shot by him. Over the years, he’s built a strong characteristic style, involving bright, garish colour and people capture unawares, often in surreal or humorous situations. His latest work however, is contemplative, consensual, subdued, and quite beautiful.â€

I’m not sure I totally agree with David, however, as with most of Martin’s work, it certainly has caused plenty of debate. Which I can’t fault.

Posted in OTHER STUDIES | Comments Off on PARR REPLIES

I’m currently reading an interesting book by Michael Billing called Banal Nationalism (Sage Publications, 1995). The thesis of banal nationalism suggests that nationhood is near the surface of contemporary life and makes a claim that nationalism is all too easily bracketed off as something extreme and irrational. Banal nationalism refers to the everyday representations of the nation which build an imagined sense of national solidarity and belonging amongst humans.

Billig suggests that nationalism is more than just a set of ideas expressed of separatists. Instead, nationalism is omnipresent – often unexpressed, but always ready to be mobilized in the wake of catalytic events. He writes: “A nation is more than an imagined community of people, for a place – -a homeland – also has to be imagined….The imagining of a ‘country’ involves the imagining of a bounded totality beyond immediate experience of place. The imaginery of the national place is similar to the imagining of the national community. As Benedict Anderson stressed, the community has to be imagined because it is conceived to stretch beyond immediate experience; it embraces far more people than those with which citizens are personally acquainted. The citizens of the nation state might themselves have only visited a small part of the national territory. They can even be tourists in parts of ‘their’ own land; yet it is still ‘their land’. The unity of the national territory has to be imagined rather than directly apprehended.â€

He cites examples of banal nationalism as the use of flags in everyday contexts, sporting events, national songs, symbols on money, popular expressions and turns of phrase, patriotic clubs, the use of implied togetherness in the national press, for example, the use of terms such as the prime minister, ur team, and divisions into “domestic” and “international” news, and even the weather. Many of these symbols are most effective because of their constant repetition, and almost subliminal nature.

Billig argues that the academic and journalistic focus on extreme nationalists, separatist movements, and xenophobes in the 1980s and 90s obscured the modern strength of nationalism, by implying that it was a fringe ideology. He notes the almost unspoken assumption of the utmost importance of the nation in political discourse of the time, for example in the calls to protect Kuwait during the 1991 Gulf War, or the Falkland Islands in 1982. He argues that the “hidden” nature of modern nationalism makes it a very powerful ideology, partially because it remains largely unexamined and unchallenged, yet remains the basis for powerful political movements, and most political violence in the world today. However, in earlier times calls to the “nation” were not as important, when religion, loyalty, or family might have been invoked more successfully to mobilize action.

To find out more about various academic studies on the topic of nationalism, visit the The Nationalism Project website here.

Posted in RESEARCH | Comments Off on BANAL NATIONALISM