MACDONALD & SMITH

March 8th, 2010 adminThe other week, in the space of a couple of days, I somewhat bizarrely happened across the siblings of two British photographers in two separate circumstances – the first during a lecture I was giving at the Cleveland College of Art & Design and the second during a visit to Martin Parr’s studio in London. Interestingly both the photographers in question were born in the north east of England within a year of each other and have spent most of their photographic careers documenting the community where they grew up and lived. They have both produced historically significant bodies of work and have, to varying degrees, shunned the spot light over the years.

The photographers in questions are Ian Macdonald (b.1946, UK) and Graham Smith (born 1947, UK).

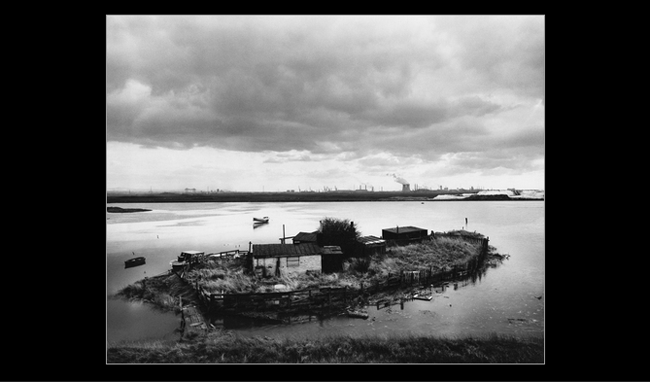

After labouring in a string of jobs in heavy industry, Ian Macdonald went on to forge a career in photography and has spent the last forty years photographing the hinterland of his native Cleveland. He has gained acclaim for his powerful studies of the industrial and post-industrial world he was born into, with its smoking chimneys, its dockyards and salt-of-the-earth people. His work examines the relationship between man and his environment, and has often focused upon the heavy industry based around the River Tees, particularly in the 1970s and 80s. His rich and extensive work includes ‘Greatham Creek’, ‘The Tees Estuary’ and, exploring the villages of the Esk Valley, ‘Quoits’ (photographs from which can be seen on the Side Gallery website here). In 1987, with the painter Len Tabner, he produced the book ‘Smith’s Dock – Shipbuilders’, exploring the later days of the construction of North Islands, the last ship to be built by this shipyard on the River Tees.

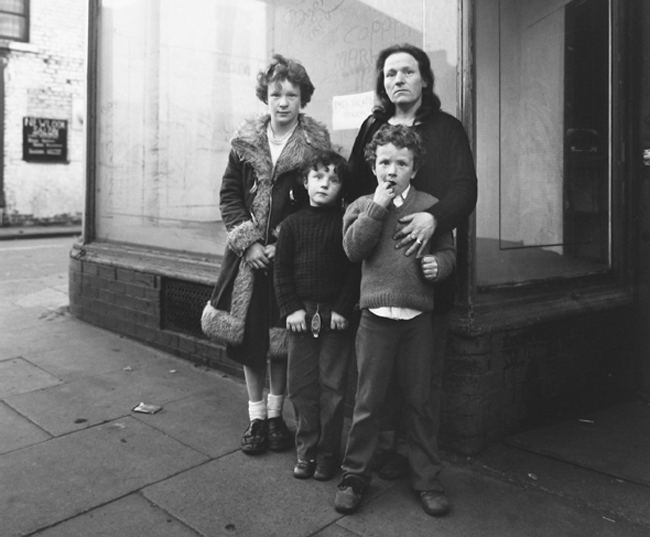

Greatham Creek © Ian Macdonald

Greatham Creek © Ian Macdonald

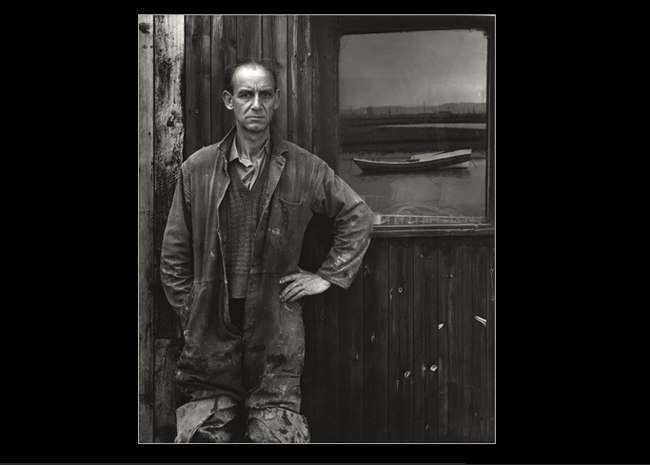

Ken Robinson © Ian Macdonald

I thought I’d let Macdonald talk about his work in his own words, with extracts taken from a speech he delivered at the Press Conference for the launch of ‘Art of Photography’ exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1989 (which is as poignant now, as it was then):

“Many of the images which photography spawns and which are common to us all are either to report an event or to sell a product. All the material we see is mechanically reproduced. We are fed it in dollops between dramatic headlines, advertisements, sport, fashion and a whole host of other things. This imagery varies in size from postage stamp to giant billboards, each designed for a particular purpose essentially to capture and hold our attention for some ulterior motive which in so many cases has little to do with the actual image. This bombardment gives the art of photography an indifferent name, the images are cropped, manipulated and mutilated which discredits the photograph. Such material, being so unavoidable, can only precondition the ways in which people look at and consider photographs.

Within sight and sound of the largest blast furnace in Europe © Ian Macdonald

Young John Allison © Ian Macdonald

“Two of the most obvious things about photographs intrigue me, their stillness and silence; these are for me also their major strengths. Photographs, being silent and still, preclude reality other than in that most superficial sense of the representation of an apparent likeness. In precluding reality they fall into the realm of myth, where everyone is free to invent by association as they see fit, for the meaning of each photograph is conditioned by those personal experiences the onlooker takes to viewing each image. This makes many types of photograph universally accessible. It follows that it is close to impossible even to contemplate the irrelevant notion, which is, are photographs Art? As Paul Strand so succinctly stated “All painting is not art”.

Largest blast furnace in Europe at Redcar, Teesmouth © Ian Macdonald

Largest blast furnace in Europe at Redcar, Teesmouth © Ian Macdonald

“It is the viewing of real photographs, which is singularly important. The actual photographic print, from the negative, as the artist made it is very particular. Each original print though made from one negative is, in fact, unique. The size, tone and surface of the print and not least the image, which is what it is all about, are all specific to the artist. To be of any real value it is better for the artist to have made the print. Considering photographs need to be given both time and space, and like any other “good” piece of artwork the “good” photograph will grow with viewing. It will develop, freeing the mind, as looking and reflecting will inevitably raise other notions, associations and feelings and so a process of enrichment goes on.” Read Macdonald’s full statement here.

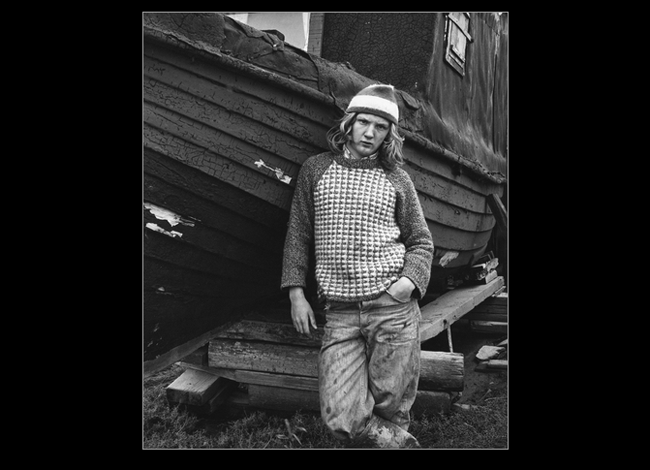

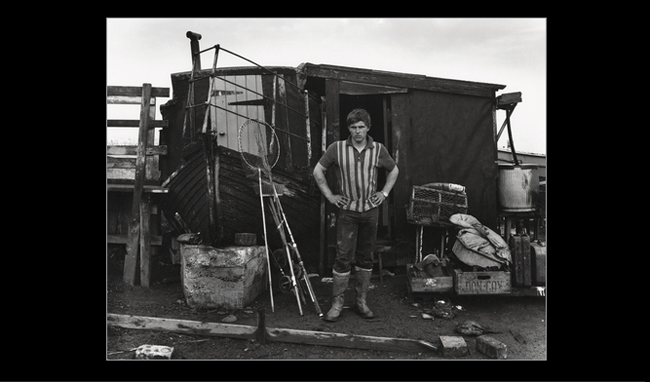

Young lad, houseboat side © Ian Macdonald

Young lad, houseboat side © Ian Macdonald

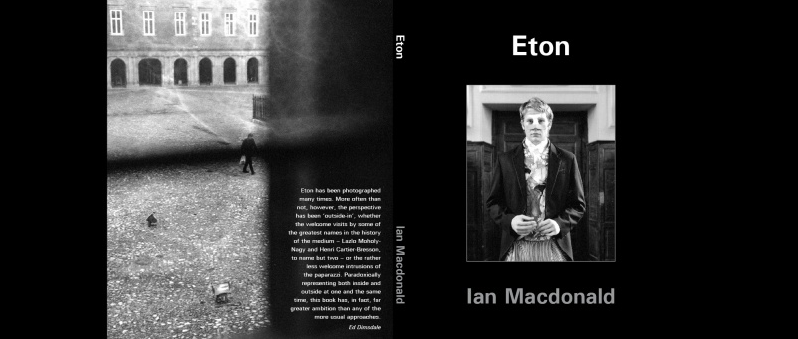

Macdonald has produced several books, most notably Eton (2007) – Between 2006-2007 he lived as part of the famous Eton College community as artist-in-residence, teaching and making a photographic response to that environment. He has also collaborated with painter Len Tabner on the publications Smith’s Dock Shipbuilders (1987) and Images of the Tees (1989). Macdonald has exhibited widely and his work features in many collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; the Arts Council of England; and the Danish Royal Library, Copenhagen.

Eton by Ian Macdonald

You can find out more about Macdonald’s work and purchase copies of his books here. Also, Macdonald’s son, Jamie, has made a film which looks at his father’s unique practices (he still process and prints his own work at home in the darkroom) and individual philosophy. As well as showing photographs from his archive, it captures the artist making new work. Martin Parr is quoted on the jacket sleeve saying “This charming film gives an insight into this process and working methods. We learn how he shoots and prints these spectacular images, using analogue technology and patience, which is so rare in our digital age.” You can purchase a copy of ‘Shooting Time’ by sending an email to mac.duncan@virgin.net.

A few days after meeting Jamie Macdonald in Darlington, I had the unexpected pleasure of meeting Graham Smith’s daughter in London. Like Macdonald, Smith photographed extensively in the north east of England and particularly in the city of Middlesbrough.

The Black Path, Middlesbrough © Graham Smith, 1986

The Black Path, Middlesbrough © Graham Smith, 1986

Smith was born into a family whose work, class and culture, on his father’s side, was rooted deeply in the heavy industry of iron making for at least four generations. His beginnings in photography came at Middlesbrough College of Art and later the Royal College of Art. From the start his subject was close to home and Smith spent more than a decade making photographs of his friends and relatives and the pubs they frequented around the South Bank area of Middlesbrough.

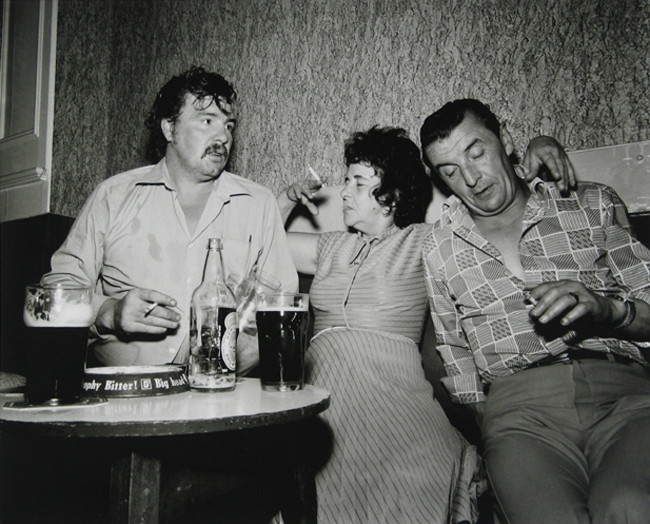

I Thought I Saw Liz Taylor and Bot Mitchum in the Back Room of the Commercial, Middlesbrough © Graham Smith, 1984

I Thought I Saw Liz Taylor and Bot Mitchum in the Back Room of the Commercial, Middlesbrough © Graham Smith, 1984

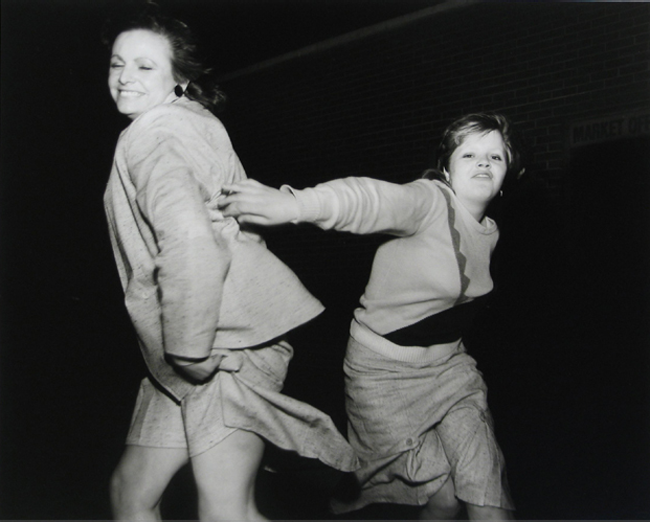

Dancing Girls, Middlesbrough © Graham Smith, 1985

In the 1970s Smith was among the photographers central to the Side Gallery in Newcastle, and created a series of photographs that showed working-class people in the north of England that were in a documentary style but were in fact montages. Work from the 1980s would show people within townscapes, and in the words of David Alan Mellor, were “atmospheric, steeped in popular (and personal) memory — dark, romantic places with all the melancholy attributed to Eugène Atget’s familiar locations”. Another Country, a joint exhibition with Chris Killip held in London at the Serpentine Gallery in 1985, was generally well reviewed but to some appeared passé in the light of the new “postmodern” work of Martin Parr and others (Killip’s work from the project became the foundation of his book, In Flagrante).

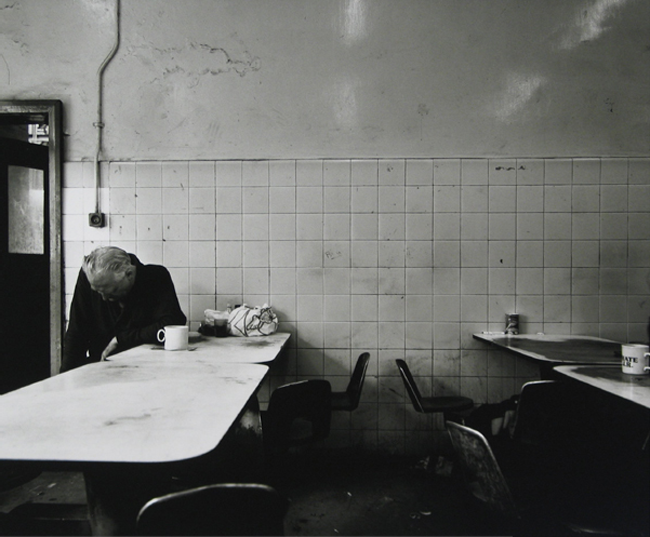

Thirty – Eight Bastard Years on the Furnace Front Mess Room for No. 4 and No. 5 Furnaces, Middlesbrough © Graham Smith, 1983

Thirty – Eight Bastard Years on the Furnace Front Mess Room for No. 4 and No. 5 Furnaces, Middlesbrough © Graham Smith, 1983

No Tickets Taken, Middlesbrough © Graham Smith, 1982

No Tickets Taken, Middlesbrough © Graham Smith, 1982

The inevitability of working for life in the iron and steelworks troubled him and disillusioned with photography, Smith stopped making photographs in 1990, when he became a professional frame maker. Although he has continued a life-long investigation of his working class roots through his research and writing. Recently his work could be seen in Granta 95: Loved Ones, published in 2006, where he wrote an essay called ‘Albert Smith’, about his father’s life:

“My dad, George Albert Newton Smith, was born into a family whose culture, work and class were rooted deep in the heavy industry of ironmaking. In hope of a better life, his great grandfather left the ironstone mines at Rosedale during the middle of the nineteenth century to look for work in the fast growing industrial town of Middlesbrough. He was the first of four generations to work for the powerful ironmasters who, with their vision of an iron and steel metropolis, built so many blast furnaces along the River Tees that it was said one man could not count them all in one day. There was a job for any man who had the strength to work and the will to give loyalty for life to the company. As a young boy older than his years my dad knew that when his days at school ended, by tradition he would follow his own dad into the Cargo Fleet Iron Company. Working together under the structure of three formidable blast furnaces, they repaired the large steam cranes used for moving ironstone and slag. His older brother Bill worked as a front man at the foot of one of those blast furnaces, but some years later was crushed to death when the ageing furnace, under too much pressure, exploded.” Graham Smith, 2006

Outside the Commercial, Middlesbrough © Graham Smith, 1982

Despite Smith’s work being held by several major collections including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, it has been almost impossible over the past twenty years to see his photographs. More recently he seems to have been coming (ever so slightly) out of the shadows with his prints now represented by Eric Franck Fine Art in London – there were some fabulous prints on show at last year’s Paris Photo – and Rose Gallery in LA.

A quote on Eric Frank’s website maybe best sums up Smith and his work – “People, pubs, stories, photographs, writing and ego have all been important to him and Smith’s photographs can be seen as an obsession to understand values, good and bad, of the culture he left behind.”

You can find out a bit more about Smith on wikipedia here.

Both Macdonald and Smith are from a generation of photographers who were driven to document the experiences of the places where they grew up and lived, charting the injustices of society but also the stoicism and richness of the characters they photographed. Neither were interested in awards and accolades, rather they wanted to tell the stories of those around them.

March 18th, 2010 at 9:49 pm

I’ve just received an email from Ian Macdonald with this little titbit of information-

“Graham and I go back a long way together having both started Teesside College of Art on the same course, Visual Communication, in 1968. He was a fanatical photographer virtually from the start, where as I was more interested in painting and drawing and went on to study painting at Sheffield in 1971 while Graham went to the RCA in London. We collaborated together with Chris Killip and Len Tabner forming a loose group called “Cleveland practicing artists” raising funding from Northern Arts and the local authority to fund our practice for three years. Graham and Chris went on to produce ‘Another Country’ while Len and I produced ‘Smith’s Dock’ and ‘Images of the Tees’. It was an interesting time to say the very least.”

June 21st, 2010 at 3:01 pm

Looking at one of the photos showing the back room of the Commercial I recognised one of the people in it the one on the left is Anthony Burges from Grangetown. I’m not certain weather the guy is still alive but he used to be a regular in the Commercial in South Bank Benit’s Corner not Middlesbrough.I used to live in Upper Jackson Street which was the next sreet down from the Commercial but it is all pulled down now as is a lot of South Bank. There are still a lot of good people in South Bank and I still go down there to see my family when I can and we go to the Peters Club on Normanby Road for any family get togethers and we all have a good time.

February 8th, 2014 at 3:08 pm

I would like to know the identity of the woman with closed eyes standing outside the commercial in 1982. If anyone has knows if they could drop me a line. Thanks.