September 14th, 2008 admin

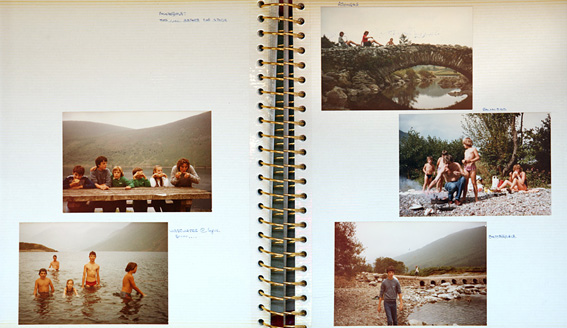

After lunch yesterday, Mum pulled out some old photo albums from bygone holiday’s in the Lake District. Nothing like family nostalgia on a Sunday afternoon.

Â

On the subject of lunch, I was surprised by how many of our family photographs seemed to be centred around food. Such us eating ‘Roonies’ meat pies by Lake Ennerdale (the best pies in England reckons Mum) –

Â

Snacking on the summit of Anglers Crag-

Â

Or barbequing on the shore of Crummock Water –

Â

My Dad was a keen amateur photographer and this is one of my favourite shots from the album, captioned:

“Wastwater at 6pm, Brrrrr”

Posted in INSPIRATION | Comments Off on PICTURES FROM THE FAMILY ALBUM

September 13th, 2008 admin

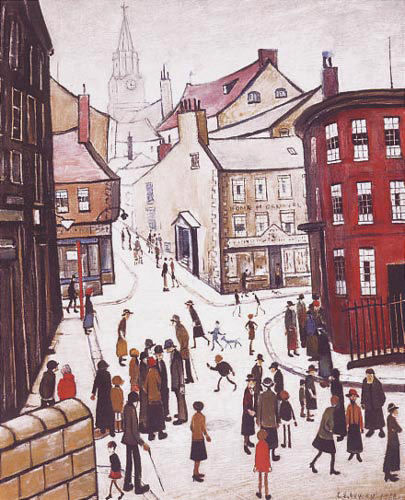

We visited Berwick-upon-Tweed last week, a town where L.S.Lowry spent a significant amount of time over the course of four decades. He visited the town many times from the mid-1930’s, often on holiday with his family, until the summer before he died. This gives me a good excuse to post up some of my favourite Lowry paintings, as part of my series on the Art of Leisure.

Laurence Stephen Lowry (born Stretford, 1887; died Glossop, 1976) was the only child of Robert and Elizabeth Lowry. He started drawing at the age of eight and in 1903, he began private painting classes which marked the start of a part-time education in art that was to continue for twenty years. In 1904, aged 16, Lowry left school and secured a job as a clerk in a chartered accountants firm, he remained in full time employment until his retirement at the age of 65. His desire to be considered a serious artist led Lowry to keep his professional and artistic life completely separate and it was not disclosed until after his death that he had worked for most of his life. He initially studied evening classes at The Manchester College of Art under Pierre Adolphe Valette a French impressionist painter one of whose specialities was urban scenes of Manchester. Later he learned the art of portraiture from the American painter William Fitz. It was from these artists that Lowry developed his trademark of stylised figures upon an industrial background.

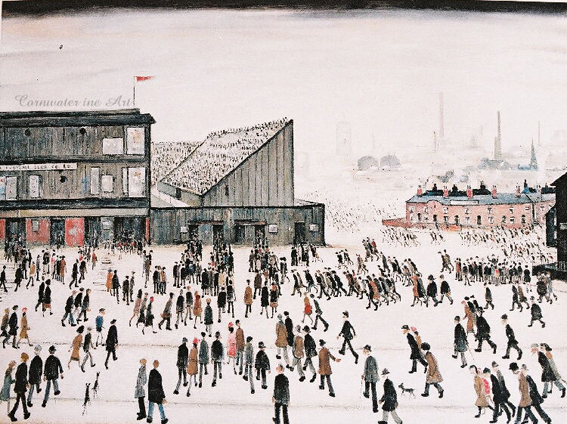

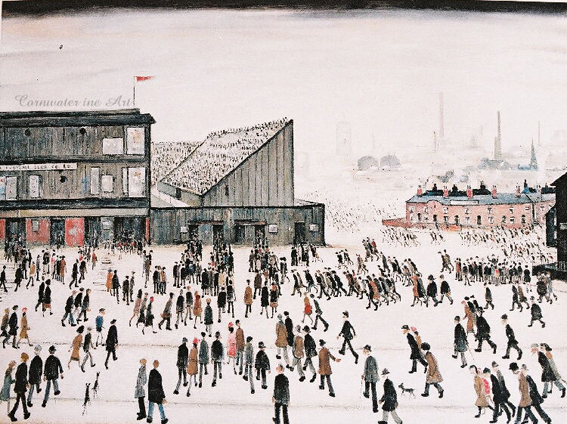

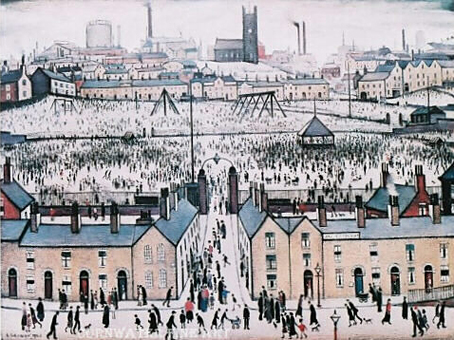

“Going to the Match” 1928, a painting which clearly depicts St. Michael’s Flags and Angel Meadow Park, Manchester.

In 1909, when in his twenties, Lowry moved to Pendlebury, where he spent much of rest of his life and drew inspiration from the mills and factories. In 1916, whilst waiting for a train, Lowry became fascinated by the workers leaving the Acme Spinning Company Mill; the combination of the people and the surroundings were a revelation to him and marked the turning point in his artistic career. Lowry now began to explore the industrial areas of South Lancashire and discovered a wealth of inspiration, remarking ‘My subjects were all around me … in those days there were mills and collieries all around Pendlebury. The people who work there were passing morning and night. All my material was on my doorstep.

“Peel Park” 1927

Typical of Lowry’s urban landscapes, this is a vivid record of life in industrial northern England. His use of spindly figures, often termed ‘matchstick men’, have become the best-known feature of his work. In early paintings, each ‘matchstick’ figure was carefully and individually depicted. From about 1930, they became less distinctive – anonymous members of the crowd. Although he often depicted industrial cityscapes with some affection, Lowry also conveyed a sense of their bleakness. He invariably used drab colours to portray grimy urban buildings and overcast skies, dominated by ever present smoking factory chimneys.

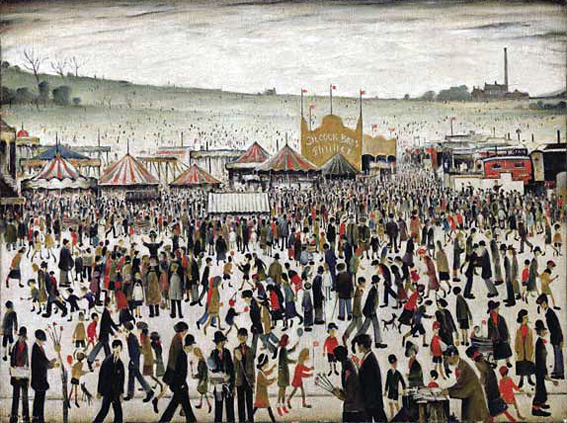

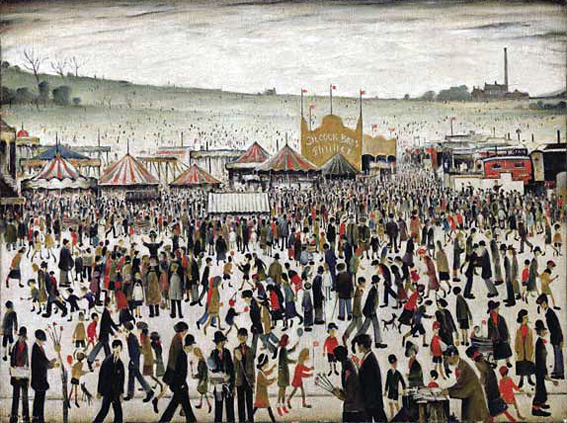

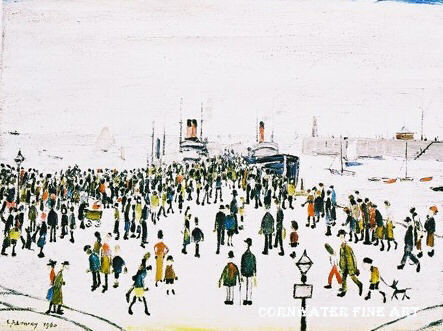

“Good Friday, Daisy Nook” 1946

This painting portrays the Lancashire town of Daisy Nook in festival mood. Traditionally, mill workers were confined to only two statutory days of holiday every year; Good Friday and Christmas Day. Every year on Good Friday, the town of Daisy Nook would stage a fair and provide entertainment to the local crowds. Managed by the Silcock family, whose name appears in the background of the painting, the fair regularly attracted huge numbers of people and still takes place to this day. The present painting depicts this annual fair in 1946, the year after the end of the hostilities of the Second World War. The Ashton Reporter stated at the time that there were ‘Record crowds at Daisy Nook’, as people celebrated a return to the fair and a return to normal life. The painting reflects post-war cheer and relief and depicts crowds of energetic, colourful characters, many holding whirligigs and flags.

On 8th June 2007 Daisy Nook was sold for £3,772,000, the highest price paid for one of his paintings at auction.

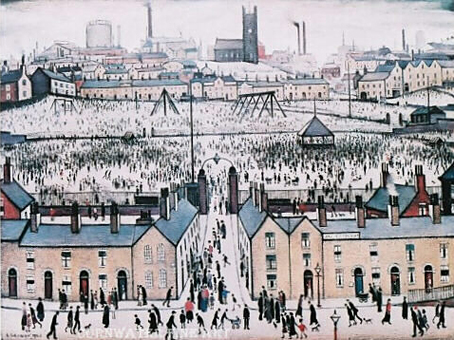

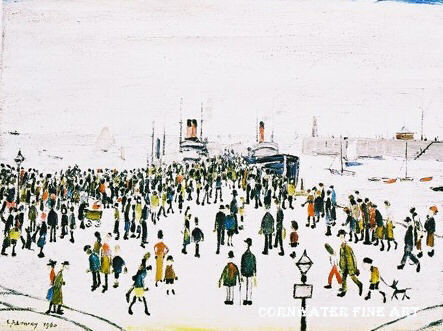

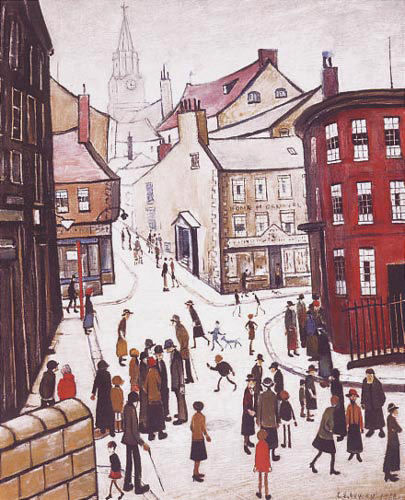

“Britain at Play” 1943

Lowry’s street scenes, peopled with workers, housewives and children set against a backdrop of industrial buildings and terraced houses had become central to his highly personal style. From now on he painted entirely from experience and believed that you should ‘paint the place you know’. Lowry’s leisure time was spent walking the streets of Manchester and Salford making pencil sketches on scraps of paper and the backs of used envelopes recording anything that could be used in his work.

“Ferry Boats” 1960

From his first exhibitions in the 1920s, he built a reputation gradually, only achieving popular success when he was in his sixities, and continued to live a simple and private life. A humble man, Lowry holds the record for turning down the most honours including an OBE. In total he turned down five honour awards and declined the CH in 1972 and 1976.

“Berwick Upon Tweed”

To read more about Lowry it’s worth looking at The Lowry Museum’s website here.

There’s an interesting article on the Guardian website by Jonathan Jones written in 2000 when the museum first opened. I’ve quoted a couple of paragraphs from the article here-

“The Lowry paintings worth looking at are the ones everyone knows. There’s no point trying to turn him into a well-rounded artist because he wasn’t one. He was a melancholy compulsive who painted the industrial north of England through deeply disturbed eyes, and caught aspects of it no one else was prepared to look at….Lowry painted the social world of Salford and Pendlebury systematically, illustrating how the factories produced people deprived of identity. His most disturbing images of the working-class crowd depict moments of supposed freedom and leisure: a drawing from 1925 of the bandstand in Peel Park shows people gathering like maggots around a piece of food, while above them the chimneys tower. Again and again he paints the crowd’s attempts at leisure as feeble reproductions of the discipline of the factory. Going to the Match (1953) makes supporting the local football team seem a desperate ritual. One of his scathing images of a crowd trying to forget the factory is called Britain at Play (1943).”

And here’s an article in The Observer by Vanessa Thorpe (March 2007) called ‘Lowry’s dark imagination comes to light’. It explores a much darker, sadder group of Lowry work rarely seen by the public, bleak sketches and paintings that include a series of disturbing and sexually deviant drawings. All had remained hidden until after the artist’s death in 1976. Lowry enthusiast Howard Jacobson argues that ignoring the bleak side of the artist’s imagination has led to him being under-rated and misunderstood by many art critics.

Posted in ART & LEISURE, INSPIRATION | Comments Off on L.S.LOWRY & LEISURE

September 7th, 2008 admin

We’re heading home!Â

Having made it to the England-Scotland border just north of Berwick-upon-Tweed we’re now going to spend the next seven days driving down the historic A1 to London then on to Brighton. Up until now we’ve made very few journey’s via motorways, preferring to take more minor (and therefore slower) roads, but it seems apt to finish the trip following the route of the Great North Road – which the modern A1 mainly follows.

The Great North Road was a major coaching route in Britain and was used by the mail coaches between London, York and Edinburgh. It is often mentioned in English literature, for example Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens. The modern course of the A1 diverges somewhat from the Great North Road, particularly where it passed through a town or village that has subsequently been bypassed, or where new motorway standard road has been constructed on a more direct route.Â

The A1 is the longest numbered road in the UK at 409 miles (658km) long and connects the capital of England (London) with the capital of Scotland (Edinburgh). It was once the busiest motorway in the country with an active roadside economy of shops, cafes, hotels. In the 1950s it was supplanted by the newly constructed M1 a speedier and smoother motorway for an England moving slickly into a modernity of effeciency and consumerism.Â

Â

Â

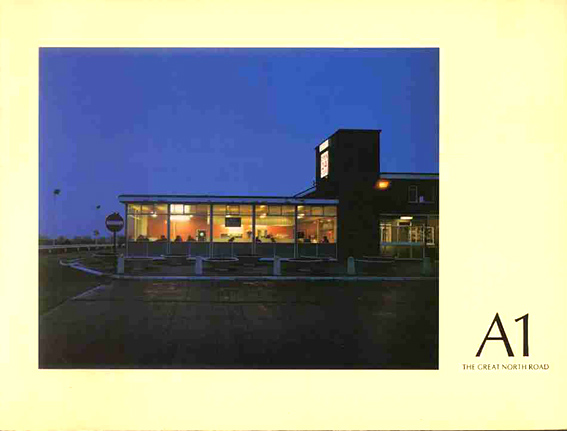

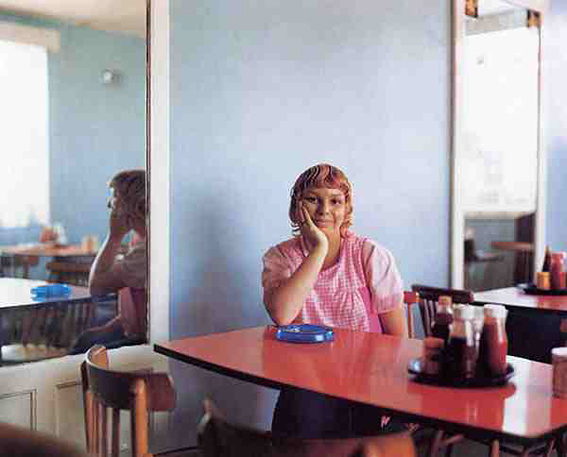

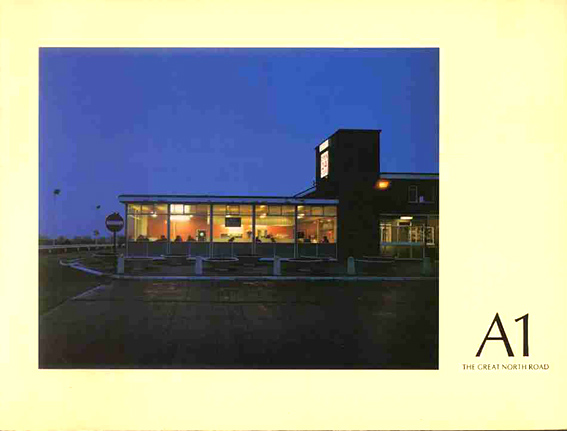

Photographically, the A1 is most readily associated with the work of British photographer Paul Graham. Graham spent two years photographing along the route of the A1 with a large format camera. The work was eventually published in 1983. A1 —The Great North Road was Graham’s first book and contained 41 color reproductions.

Â

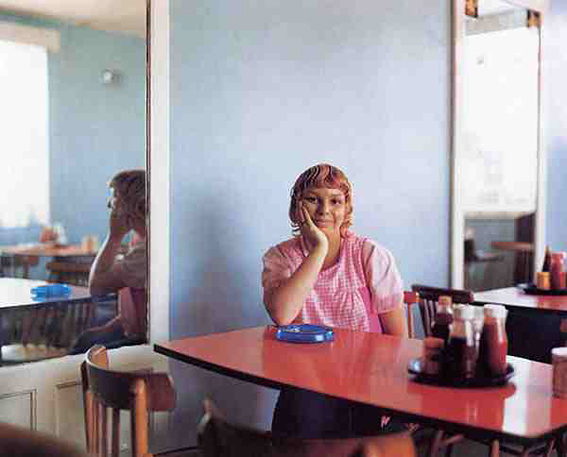

© Paul Graham, 1983

The photographs are a mournful document of a grey nowhere land in a country moving too fast to stop for a cup of tea. The book is now a valuable collectors item, valued at over £250, not bad for a self-published paper back! I’ve posted up a couple of the pictures from the book here, but you can see more on Graham’s website.

Â

© Paul Graham, 1983

According to many commentators, Graham’s A1 photographs had a transformative effect on the black and white tradition that had dominated British art photography till that point. This work, along with Graham’s later photographs of the 1980s – the colour images of unemployment offices in Beyond Caring (1984-85), and the sectarian marked landscape of Northern Ireland Troubled Land (1984-86) – were pivotal in reinvigorating and expanding this area of photography, by both broadening it’s visual language, and questioning our notions of what such photography could say, be, or look like.   Photographers like Martin Parr made the switch to colour soon after, and a new school of British Photography evolved with the subsequent colour work of Richard Billingham, Tom Wood, Paul Seawright, Anna Fox, among others.

Â

Posted in INSPIRATION, PLACES, TRIP LOGISTICS | 5 Comments »

September 6th, 2008 admin

Now that my journey across England is nearing an end, I wanted to look at the notion of the road trip in photography. While I’ve already touched on the timeline of British photographers who have used the road trip as a vehicle for documenting England/Britain, I want to now turn my attention to the work of American photographers. I’ll do this over several blog entries (I will look at European photographers in a future post).

Highway culture has long been a quintessential part of American identity and is also reflected in the canon of contemporary American photography who have worked within the tradition of the road trip across America. Names such as Jeff Brouws, Tim Davis, William Eggleston, Mitch Epstein, Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Todd Hido, Dorothea Lange, Ed Ruscha, Lise Sarfati, Stephen Shore, Rosalind Solomon, Alec Soth, Mark Steinmetz, Joel Sternfeld, and Garry Winogrand and others, have all embraced the genre. Several of whom have been major influences in my own work (particularly in Motherland), notably the work of Stephen Shore and Joel Sternfeld.

By way of an introduction to the genres I’m posting up details of an exhibition that was held at the Yancey Richardson Gallery last summer called Easy Rider: Road Trips Through America, which focussed on the road trip in American photography.

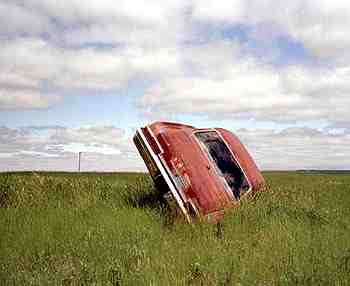

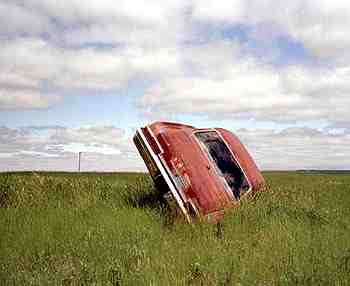

Jeff Brouws, Route 248, Four Buttes, Montana, 2004

The following text is taken from the Easy Rider exhibition press release-

“Easy Rider explores the common themes of social commentary, cultural geography and photographic biography produced by the marriage between the road and photography. Included are photographs and videos dating from 1935 to 2006.

The road allowed Farm Security Administration photographers Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans to document the plight of Americans suffering floods and dustbowls during the Great Depression. Similarly bleak, Robert Frank’s mid 1950s road trips yielded a portrait of the nation at odds with the projected optimism of the era and culminated in The Americans, a landmark publication, which influenced generations of later photographers.

The open road as a symbol of freedom is exemplified in Allen Ginsberg’s 1964 shot of Neal Cassady at the wheel of Ken Kesey’s Merry Prankster bus; Cassady’s incessant cross-country journeys were a primary inspiration for Jack Kerouac’s definitive Beat generation novel On the Road. Having spent four years riding with the motorcycle gang the Outlaws, Danny Lyons produced the book The Bikeriders, which emblazoned motorcycle counterculture onto the American psyche and inspired the film Easy Rider.

Subsequent generations of photographers continued to take to the road in order to explore the cultural landscape. Traveling on a 1969 Guggenheim to study the effect of the media on public events, Garry Winogrand recorded America’s restlessness through its political rallies, peace demonstrations and space shuttle launches. In the 1970s Mitch Epstein looked at recreation across America while Joel Sternfeld’s wryly-funny photographs often showed man at odds with nature. Alec Soth followed the watery artery of the Mississippi River to make pictures of the dreams; both lost and fiercely held, of those he encountered. More recently, Tim Davis traveled the country to seek out the presence of politics in today’s life; in St. Louis he found a wall mural of the United States depicted as one grotesquely stretched red state.

Several photographers have looked closely at the details and detritus of American culture for clues to its soul. William Eggleston’s photograph of an elegantly wallpapered restaurant wall plastered over with the business cards of its patrons shows commercial aspirations trumping style. On the bare chipboard walls of Reverend and Margaret’s Bedroom, Soth memorializes a moving display of family photographs while Lisa Kereszi’s discovery of a biker bar’s photographic collage of women flashing their breasts reveals the misogynist underbelly of road-worshipping motorcycle culture.

Many photographers have constructed a kind of biography of roads traveled, places visited and people encountered, often including themselves and family m embers. In 1962, Ed Ruscha photographed isolated gas stations along Route 66 filling half the picture frame with the street at his feet. Lee Friedlander frequently incorporated himself into his car images, staring into the camera through the windshield or via the side view mirror. In his witty series America and Me, recent Bard graduate William Lamson photographed himself interacting with elements of the roadside landscape, always hiding his face but freely revealing the shutter release. Poolside at a roadside inn, Stephen Shore incorporated his young wife Ginger into a minimalist composition of color and light. Accustomed to working on the road, Justine Kurland adjusted to motherhood by photographing her young son living with her in a camper van on an extended road trip.

Jeff Brouws has made a career of photographing along highways, evolving from cataloguing the relics of small town roadside architecture to documenting the negative impact of thruways in the 21st century. His 2004 image of a rusting red car upended in a field presents a pessimistic view of contemporary road culture: the car as a dinosaur on the road to nowhere.”

My subsequent posts will look at the work of individual photographers.

Posted in EASY RIDER, INSPIRATION | Comments Off on EASY RIDER – TRAVELS THROUGH AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHY PART 1

Although some marketing body has come up with the superficial branding of the Lake District as Wordsworth Country, and hordes of tourists flock to Dove Cottage every year, please permit me to post an extract from William Wordsworth’s poem The Prelude (Book 1).Â

As Sister Wendy Beckett writes in her collection of poetry Speaking to the Heart, this is Wordsworth at his most true and responsive to the numinous of his beloved Lake District. “Anyone who has stood alone and in silence, above all in the early morning or at night, knows the mysterious power of hills and water. Wordsworth stands alone in finding a voice for these almost indescribable feelings” writes Beckett in the introduction to the poem.

Â

An extract from The Prelude (Book 1) by William Wordsworth

A rocky Steep uprose

Above the Cavern of the Willow tree,

And now, as suited one who proudly rowed

With his best skill, I fixed a steady view

Upon the top of that same craggy ridge,

The bound of the horizon – for behind

Was nothing but the stars and the grey sky.

She was an elfin Pinnace; lustily

I dipp’d my oars into the silent Lake,

And, as I rose upon the stroke, my Boat

Went heaving through the water, like a Swan –

Â

When, from behind that craggy Steep (till then

The bound of the horizon) a huge Cliff,

As if with voluntary power instinct,

Uprear’d its head. I struck, and struck again

And, growing still in stature, the huge Cliff

Rose up between me and the stars, and still,

With measur’d motion, like a living thing,

Strode after me. With trembling hands I turn’d,

And through the silent water stole my way

Back to the Cavern of the Willow tree.

There, in her mooring-place, I left my Bark,

And, through the meadows homeward went, with grave

And serious thoughts; and after I had seen

That spectacle, for many days, my brain

Work’d with a dim and undetermined sense

Of unknown modes of being; in my thoughts

There was a darkness, call it solitude,

Or blank desertion, no familiar shapes

Of hourly objects, images of trees,

Of sea or sky, no colours of green fields;

But huge and mighty Forms that do not live

Like living men mov’d slowly through the mind

By day and were the trouble of my dreams.

Â

You can read the entire poem here.

Â

Posted in INSPIRATION | Comments Off on A POEM FROM WORDSWORTH COUNTRY

I’ve just come across this interview with Stephen Shore on Darius Himes’ blog while researching another post. It’s very enlightening on Shore’s work (of which much has been written). The answer to the following question particularly resonates and, dare I say it, partly explains what I’m trying to do with the 5×4 in We English!

Darius Himes- Gerry Badger has described your work as an “heroic articulation of the real.†Which to me carries connotations of the work as a support for contemplation. What do you think he means by this?

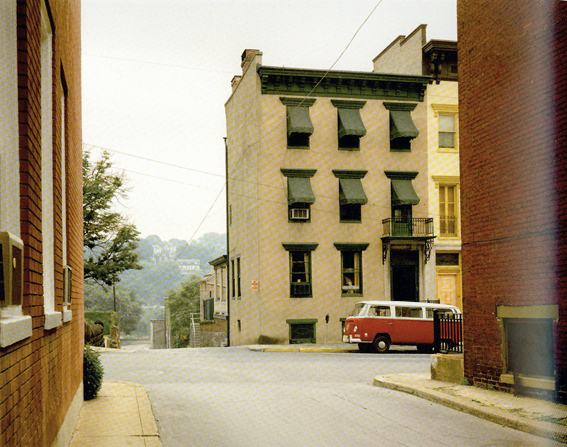

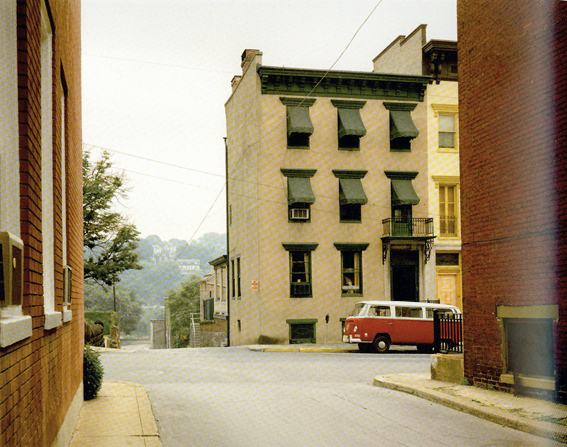

Stephen Shore- For me it has to do with the view camera. In the original Uncommon Places, there’s a picture of Eason, PA, with a red and white Volkswagen van in it.

I made that photograph on the first day that I used the 8×10; all the work in A Road Trip Journal is made with a 4×5 and then I took one short trip in ‘74 with the 4×5 before borrowing a friends’ 8×10. As you’re looking at the photograph, you realize that there is a boy sitting in the window and that you can even see his breath on the glass. It was this photograph that made me realize that with this camera I don’t have to walk across the street and photograph him. I can let him be a tiny little thing to be discovered in the picture. This was a very different technical approach from American Surfaces, for instance. So that changes the relationship of the viewer to the picture and the function of the picture. It’s not just a window directing your attention–â€here look at thisâ€â€” but is something itself to be the object of attention and to be explored. I think that’s similar to what Badger is saying.

Â

Posted in INSPIRATION | Comments Off on HEROIC ARTICULATION OF THE REAL

I came across Chris Wood when hearing him interviewed on Radio 4 about his most recent album Trespasser. Wood has been established on the English folk scene for many years and he is known for his songs of English life and his uncompromising lyrical approach. I’ve been listening to the album now for a few weeks and it is contemporary and thought-provoking. As the title implies, the theme of the album is enclosure, ownership and exclusion.Â

My favourite song is undoubtedly ‘The Cottager’s Reply’ where an elderly Cotswold cottage owner talks to the rich young couple who want to pay him half a million pounds for his home.  It’s a quiet, beautiful but at the same time, angry song.Â

Â

Wood’s music reveals his love for the un-official history of the English speaking people. As quoted on his website–

“The people of England have been unravelling the universe through their songs, stories, poetry, jokes and dances for millennia and it is this vibrant body of work which becomes the freely given treasure trove for the next generation. The simple lesson we have learnt from our ancestors is to tell nothing more or less than our own story and that the gold we are all searching for is in our own backyard.â€â€¨

There is an interesting essay in the sleeve notes to Trespasser about what he sees as the ongoing effects of the enclosure of common land in England to the present day.

You can read a review of the album here.

28th July Update-Â Check out this article written by Chris in today’s The Times, where this quote was taken:

“What I do believe is that, like it or not, the folk song of England is a living repository of our unofficial history and is possibly the single richest cultural resource we have. It is nothing less than the collective “common sense†of our ancestors and it grants us a perspective on how we have become the people we are in a way that no other “document†can.

If that is too much of an imaginative leap, try looking across the ocean. English folk song is at the heart of the music of white America, from where it evolved to tell a large part of that nation’s story. For all that time back home in England it has been ceaselessly churning, growing and evolving.

In a media-dominated culture, where style is placed over substance, it is understandable that people just don’t get it, but as the indigenous population of this country is increasingly called upon to lay its cultural cards on the table most of us agree that “Land of Hope and Glory†and “She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah,†don’t quite tell the whole story.”

Posted in INSPIRATION, RESEARCH | Comments Off on CHRIS WOOD- TRESPASSER

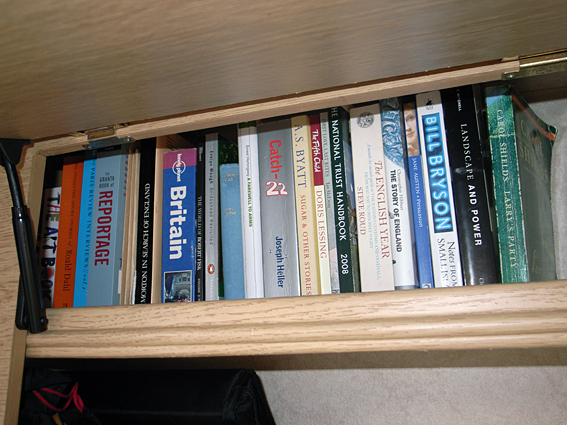

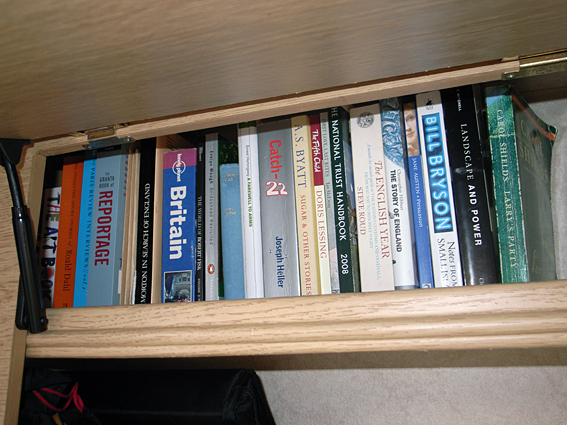

One of the interesting dilemmas before starting a journey, especially one of this length, is what reading material to pack. Space is at a premium in a motorhome so you have to choose carefully.

I’ve finally finished reading H.V.Morton’s In Search of England and debating what to start next. Although, to be honest, I’m not getting much downtime to read, hence the length of time it took me to get through Morton! It’s amazing what little opportunity I have after a daily routine of photographing, traveling, finding places to camp for the night, servicing the motorhome (filling with water, emptying sewage, putting up/taking down beds etc), checking posts on the website, researching future destinations and events, updating the blog, loading and unloading film (in a portable dark bag), eating, helping to entertain Jemima and finally Sarah and I trying to get some personal time together!

So here’s a list of what I have to choose from on our cupboard shelf-

A Dream of England, John Taylor

A Farewell to Arms, Ernest Hemingway (Sarah’s recommendation)

Brideshead Revisited, Evelyn Waugh (Sarah’s recommendation)

Catch 22, Jospeh Heller

Ed Ruscha and Photography, Sylvia Wolf

Landscape and Power, Edited by W.J.T.Mitchell

Larry’s Party, Carol Shields (Sarah’s)

Lonely Planet Guide to Britain

Notes From A Small Island, Bill Bryson

On Photography, Susan Sontag

Persuasion, Jane Austen (Sarah’s)

Sugar and Other Stories, A.S.Byatt (Sarah’s)

The Art Book, Phaidon

The English Year, Steve Roud

The Fifth Child, Doris Lessing (Sarah’s)

The Granta Book of Reportage

The Paris Review Interviews, Volume 2 (Sarah’s)

The Photo Book, Phaidon

The Story of England, Christopher Hibbert

The World of Robert Fisk

If you have any recommendations on good books for a journey around England, please post them below.

Â

Posted in INSPIRATION, ON THE JOB, RESEARCH | 3 Comments »

I’m off to the Epsom Derby tomorrow, so this seems like a good opportunity to post up the wonderfully satirical painting The Derby Day by William Powell Frith.

Â

William Powell Frith, The Derby Day (1856-8). Oil on canvas.

Â

The painting presents a panorama of modern Victorian life and when it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1858, it proved so popular that a rail had to be put up to keep back the crowds. There are three main incidents. On the far left a group of men in top hats focus on the ‘thimble-rigger‘ with his table. In the centre is an acrobat and his son, who looks longingly at a sumptuous picnic being laid out by a footman. Behind them are carriages filled with racegoers, including, on the far right, the mistress of a man leaning against the carriage.

It’s a captivating painting, which naturally, needs to be seen in the flesh. It’s on display in Room 13 of Tate Britain along with a selection of paintings under the heading ‘The Art of Leisure’ (devised by curator Christine Riding). I visited the museum for some last minute inspiration before embarking on this trip, and was lucky enough to have Tony Godfrey from Sotheby’s Institute of Art as my guide. This room felt particularly relevant.

Â

The introductory panel to ‘The Art of Leisure’ reads-

“Queen Victoria died in 1901. During her long reign the enjoyment of leisure time had spread beyond the wealthy upper classes to a wider range of people living in British cities. The lives of working people were hard, but they had greater spending power, shorter working hours and more holidays: more opportunities to enjoy themselves.

A great variety of new activities were on offer: music halls, railway excursions, fairgrounds, commercial exhibitions and sporting events; or just listening to the band in one of the new public parks. The growth of the railways enabled city people to head for the country or seaside for picnics, rambles, swimming and boating. By 1911, just over half of the population of England and Wales made at least one seaside trip every year.

Artists were fascinated with the new leisure activities, but some critics argued that everyday life was not a suitable subject for a painting unless it had a clear moral purpose. The earliest works in this display use narrative and satire to comment on contemporary morality and behaviour. But the guidance offered by later painters, such as James Tissot, is much less clear. In the decades after Victoria’s death, new styles of painting emphasised the light and atmosphere of outdoor leisure activities, rather than the lessons to be drawn for them.”Â

Â

Here are some of the other paintings on display-

Â

Joseph Mallord William Turner Sketch for `East Cowes Castle, the Regatta Beating to Windward’ No. 3  (1827). Oil on canvas.

Â

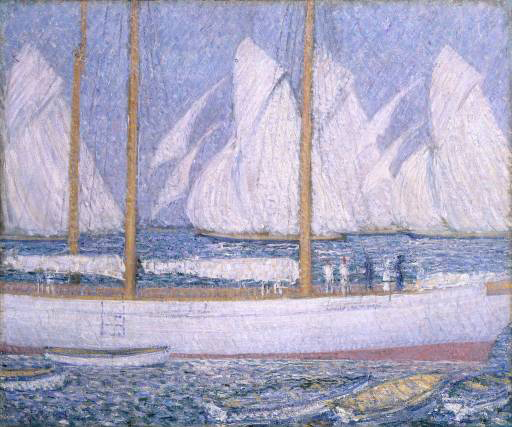

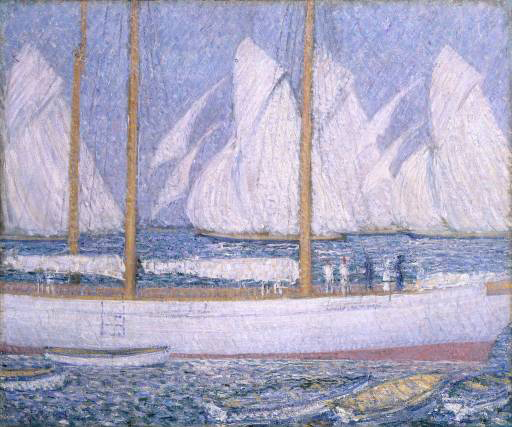

Philip Wilson Steer A Procession of Yachts (1892-3). Oil on canvas.

Â

Sir John Lavery The Golf Course, North Berwick (1922). Oil on canvas.

Â

James Tissot Holyday (circa 1876). Oil on canvas.

Â

Walter Richard Sickert The Front at Hove (1930). Oil on canvas.

Â

Charles Cundall Bank Holiday, Brighton (1933). Oil on canvas.

Â

Philip Wilson Steer The Beach at Walberswick (circa 1889). Oil on wood.

Â

Charles Conder By the Sea: Swanage (circa 1901). Oil on canvas.

Â

Sir Stanley Spencer The Roundabout (1923). Oil on canvas.

Â

Posted in ART & LEISURE, INSPIRATION, RESEARCH | Comments Off on THE ART OF LEISURE

We were at the Wychwood Festival this weekend, held at Cheltenham Race Course. An intimate event started four years ago, which has quickly established itself as the first major festival of the summer season.

The highlight was The Imagined Village who performed on Sunday night.Â

The Imagined Village is an ambitious project bringing together folk musicians including Eliza and Martin Carthy with established pop and rock acts – Paul Weller, Billy Bragg – and a flavour of multicultural England from Transglobal Underground, the British-Asian singer Sheila Chandra and the poet Benjamin Zephaniah.

The project has been masterminded by Simon Emmerson, a DJ and producer best known for his work with the Afro-Celt Sound System and with African acts such as Baaba Maal and Manu Dibango. Emmerson was determined for traditional English music to assume its rightful place on the “world music” scene.Â

The aims of the project, as stated on their website, are:

“We started this project back in 2004 as a way of exploring our musical roots and identity as English musicians and music makers. There is a lot of discussion in the media at present about what constitutes the English identity, we hope to use this web site and our first record as a contribution to this discussion. We are not trying to re-invent the wheel or for that matter re-invent the English folk tradition. What we are interested in is building an inclusive, creative community were we can engage in the debate passed down to us by the late Victorian collectors of English song, dance and stories spearheaded by Cecil Sharpe and his contemporaries.

We all walk in the footsteps of our Victorian song collecting ancestors but feel it is more relevant now than ever to question who decides what it is to be authentic and English and more importantly what it is that makes us proud to be English musicians. We are not providing a manifesto or for that matter any easy answers.”

Read more about the project in an article which featured recently in the New Statesman.

Or find out more about the individual artists-

Benjamin Zephaniah

Billy Bragg

Chris Wood

Eliza Carthy

Johnny Kalsi

Martin Carthy

Paul Weller

Sheila Chandra

Simon Emmerson

The Copper Family

The Gloworms

Tiger Moth

Trans-Global Underground

Tunng

Â

Posted in EVENTS & PASTIMES, INSPIRATION | Comments Off on THE IMAGINED VILLAGE