November 20th, 2008 admin

I’ve recently come across the photography blog American Suburb X, which features reviews of work of well known (and not so well known) photographers alongside lively prose by author dR. It’s definitely worth looking at.

Oh, and the current issue has a rather flattering review of Motherland which you can read here!

Posted in MISCELLANEOUS | Comments Off on IN THE SUBURB

November 11th, 2008 admin

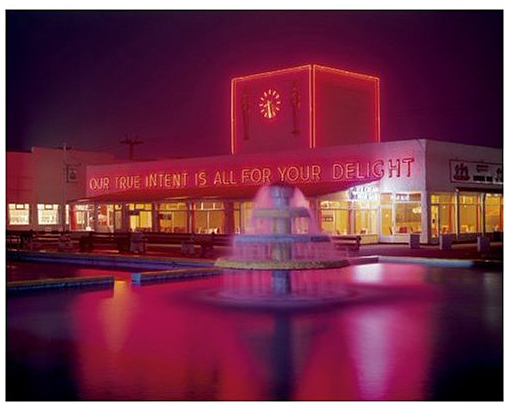

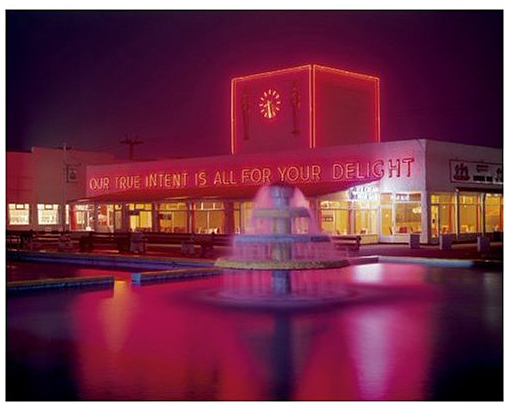

I’m knee deep in nappies and won’t be back on the blog this week. So in the meantime I thought I’d run a small competition and giveaway a copy of the wonderful book Our True Intent Is All For Your Delight: The John Hinde Butlin’s Photographs to one reader.

As you know, I’ve recently been looking the work of photographers who have made significant documentaries exploring their homeland, which was somewhat inspired by a comment Joel Sternfeld recently made in an interview in PLUK magazine (Summer 2008), where he said “I thought about ‘home’ and its power, and about an idea I have that many of the great practitioners photograph their ‘home’ landscapes.â€

While I’ve concentrated my efforts on looking at the work of British photographers and in my Easy Rider series, the work of American and German photographers, now I’d like to hear your suggestions. Please post or email me your ideas of work by photographers (which could be you) that have explored their own ‘homeland’ with a short explanation of why you think their work is important. By homeland, I mean the country where one was born or now considers their home.

I’m particularly interested in countries other than those I’ve already looked at.

One reader will receive a copy of Our True Intent and a signed copy of Motherland.

Posted in EASY RIDER | 15 Comments »

Our second daughter, Florence, was born this morning.

Oh, and that bloke Obama was elected President of the United States!

Posted in MISCELLANEOUS | 6 Comments »

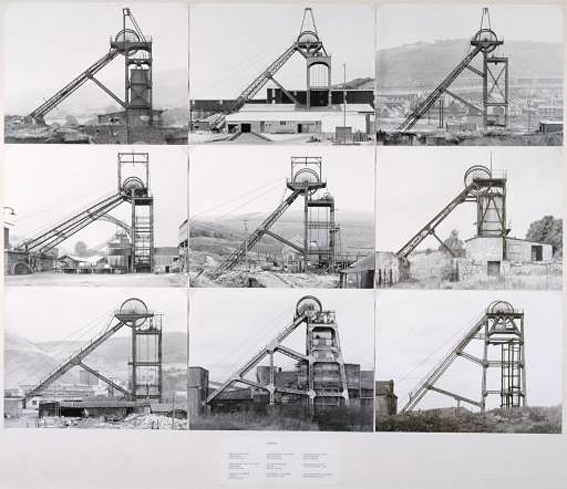

It’s probably worth making a quick nod to the photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher given, not just their significant influence on contemporary German photography, but also their method of working.

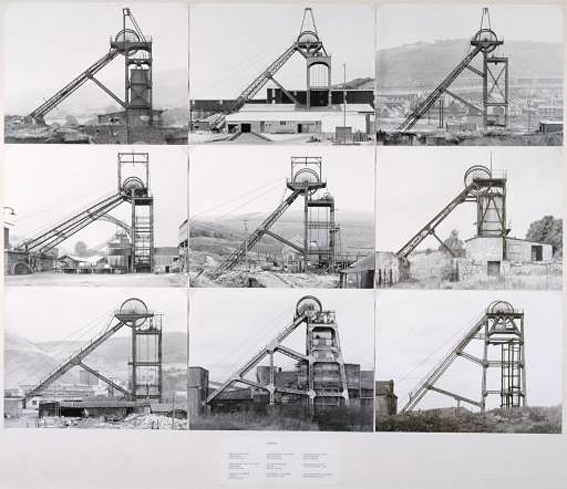

From the beginning, the Bechers worked systematically at their task. They undertook countless journeys in their Volkswagen van, which also served as a bedroom, improvised darkroom, and mobile nursery for their son, Max, who was born in 1964. The routes they staked out in their Düsseldorf studio took them to the far corners of western Europe and north America, through Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France and Luxembourg. In 1966, they undertook a six-month journey through England and south Wales, taking hundreds of photographs of the coal industry around Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, Nottingham and the Rhondda Valley.

Pitheads, 1974 © The Bechers. All taken at collieries in Britain. From the Tate Collection.

Bernd Becher was born August 20, 1931, in Siegen, Germany. He studied painting and lithography at the Staatliche Kunstakademie Stuttgart from 1953 to 1956 and studied typography at the Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf from 1957 to 1961. Hilla Becher was born Hilla Wobeser on September 2, 1934, in Potsdam, Germany. She studied painting at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where she met Bernd Becher. The two artists first collaborated in 1959 and were married in 1961. They began working as freelance photographers, concentrating on industrial photography.

From their first series of photographs of water towers, the artists have not veered from architectural portraiture subjects, using both industrial and domestic structures such as gas tanks, silos, framework houses, and the like. They were given their first gallery show in 1963 at the Galerie Ruth Nohl in Siegen and by 1968 were exhibiting in the United States as well as in European cities outside Germany.

You can see a portfolio of their images here.

Bernd Becher died in 2007, and you can read an obituary on The Guardian here.

And, of course, you can read an interview with Hilla Becher entitled ‘Of course we were freaks’ by Tobias Haberl and Dominik Wichmann on the Joerg’s Conscientious blog here.

Posted in EASY RIDER | Comments Off on EASY RIDER, Part 7 – THE BECHERS

Photographer Owen Richards has just emailed me and suggested I take a look at this film by Christopher Petit.

RADIO ON (1979) is described as a post-punk journey through 70s England. It’s become a cult film since its initial release and some claim it’s one of the most striking feature debuts in British cinema. Co-produced by Wim Wenders and featuring Sting’s first film performance, RADIO ON is austere in narrative and captures the lurking disenchantment of the British youth movements of the time.

RADIO ON was photographed in monochrome by Martin Schaefer (Wenders’ cinematographer), and its soundtrack featured tracks by Bowie, Kraftwerk, Lene Lovich, Ian Dury and Wreckless Eric. Petit’s anti-road movie follows a London DJ (David Bearnes) as he travels to Bristol to investigate the mysterious death of his brother, and offers a unique, compelling and even mythic vision of a late 1970s England.

It’s been described as “a subtle, masterfully understated meditation on late 1970s Britain. Its loose, barely-existent narrative is told through a rich monochrome print of ghostly whites and glossy blacks: presenting fractured, dehumanising Ballardian urban backdrops alongside gloomy, ethereal rural landscapes. Resonating panning shots of cityscapes, saturated with the detritus of defunct nineteenth century industry, alongside boarded-up, dilapidated buildings, abandoned petrol stations and empty hotels all contribute to a profound and poignant sense of simultaneous wonder and dread. Beautifully crafted static shots emphasise the empty meaning of modern existence through images of blank, static television screens, monotonous flickering marquees and lurching fuel-pump dials.”

You can watch a trailer here.

I’m going to add it to my viewing list!

Posted in MISCELLANEOUS, OTHER STUDIES | Comments Off on RADIO ON

Continuing my Easy Rider series, I’m now going to turn to the work of two German photographers who have produced studies of their homeland and whose work I’ve found particularly inspiring. They are Joachim Brohm with his book Ruhr (Steidl, May 2007) and Peter Bialobrzeski with his book Heimat (Hatje Cantz, out of print).

In this post, I’m going to look at the book Ruhr.

I was introduced to the work of Joachim Brohm by Marcus Schaden in Arles last year. Marcus was very excited about Brohm’s recently published photographic series, which documented the German Ruhr area during its industrial decline from the late 1970s to the mid-80s. And I could see why, it’s a superb book. The photographs have a freshness to them, while retaining a clear and focused aesthetic. There are 50 pictures in total, the earliest going back to his photographic training at the Essen Folkwang School from 1977, and an insightful introductory essay (Topographies of Anonymity) by Heinz Liesbrock.

One of the most interesting aspects of this work is the fact that Brohm became one of the first to engage with the issues raised by American photography – the landscape photography of the nineteenth century and the topographical photography from 1970 onwards – and transport them into a European context. As a result, Ruhr is an integral link between USA and European photography (or as Liesbrock describes it “a cross fertilisationâ€) and its special significance is revealed with this first complete monograph.

Bochum, 1983 © Joachim Brohm

Liesbrock sees the work of Brohm, along with Michael Schmidt and Heinrich Riebesehl, as among the first European photographers to engage intensively with the aesthetics of American photographers like Robert Adams, William Eggleston and Stephen Shore. He writes: “All of them understood the gaze of the American photographers as a framework in which they can deal with questions from their own German cultural context, and this is why it is not by chance that they all begin their engagement with the Americans in the familiar context of their immediate home environment.†For Schmidt this is Berlin, for Riebesehl the agrarian landscape of Lower Saxony, for Brohm it is the Ruhr. This engagement with American photography, which today is recognized as classical, was at that time a matter for a select few.

In describing Brohm’s aesthetic, Liesbrock writes: “At first sight there are two aspects in particular that catch our attention. First the directness of the photographic gaze with which he addresses the visible and the unpretentious way in which he translates it into a restrained compositional structure….The pictorial aesthetics developed by Brohm are intentionally kept close to amateur photography. A second important aspect of his conception of the image is his use of colour. For a photographer with artistic ambitions to use colour as a medium was still the exception in Europe around 1980….Brohm’s Ruhr, as we encounter it in his pictures, is also characterize by this wish to expose specific pictorial energies in the banal, the seemingly expressionless.†Later on in his essay Liesbrock describes Brohm’s use of colour as a “restrained colouration to reflect the uneventfulness of the scenery of the Ruhr as a place where nothing happens…He develops colour into a stylistic feature devoid of any strident notes….The colour seems flat, it has no radiance but rather remains self-contained.â€

Bochum, 1982 © Joachim Brohm

To a large extent Brohm turns his gaze on urban life at the edges of the Ruhr, where existence tends to have a rural feel, where shopping centres and small business zones have established themselves. As Liesbrock puts it “a placid zone of seemingly uninterrupted leisure time.†Brohm observes people from a distance, avoiding intimate perspectives and arranges expressions of human activity in harmony with the architecture and the landscape. An elevated camera position is a common theme. “People seemed safely at home in it, in fact lulled into repose, inconsequential, they have no echo. This familiar, everyday ambience assumes a form of quiet monumentality†says Liesbrock.

Essen 1982 © Joachim Brohm

Liesbrock closes his essay by describing Brohm’s significant contribution to recent photographic history and explaining why his work has gone unacknowledged for so many years (overlooked by the large-format colour photography that had been developed in Bernd Becher’s class in Dusseldorf that became the centre of attention – works of Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth…) and has only now been published, twenty years after the photographs were taken. He writes, Brohm’s work “constitutes a central link between photography in the USA and Germany since 1970. Anyone looking at the sequence of pictures in this book, will also discover in Ruhr a work of unmistakeable artistic vitality, which will be of lasting significance, independently of all historic coordinates.â€

Joachim Brohm, born in Dülken, Germany in 1955, studied visual communication and photography at the University of Essen and at Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio. He has had one-man shows at Fotoforum Bremen; Spectrum Photogalerie in the Sprengel Museum, Hannover; Museum Folkwang in Essen; and Fotomuseum in Munich. Brohm lives in Essen and Leipzig.

If you want to see more of Brohm’s work, he’s published two further books with Steidl, Areal and Ohio.

Posted in INSPIRATION | Comments Off on EASY RIDER, Part 6 – THE GERMAN CONNECTION

There’s a brief reply from Martin Parr on the Flickr group in response to a comment about his Newcastle photographs, which I’ve copied out here-

As a relatively recent resident of Newcastle (I grew up in Sussex, moved from London 5 years ago) I was appalled by the supplement on the city in this Saturday’s Gaurdian.

It is the most biased piece of misrepresentation of a city I have ever perused…

The photos are beautiful – no doubting that – but as an overview of a city (which this purports to be) it misses out more than 1/2 of the population, instead concentrating solely on the working class.

It lends one to think that the photographer had an agenda – and even in his opening spiel goes on about how “industry has not been replaced” and implies that the city is depressed… It almost begs the question, did he really come here?

Examples:

pic of tattooed man bbqing on Cullercoats beach – what about the yummy mummys and their bugaboos who I saw there every sunny day last summer?

pic of woman at Races, fag in hand, bottle of Echo Falls – did he search for these people?? – what about the boxes full of business people and solicitors, drinking premium champagne who gave up smoking, if they ever did smoke, when the ark docked…

and so moving on from dance halls and bingo to the rest of the population… what about a pic of the boys outside the Royal Grammer School; a glance at the >£1m houses in Gosforth or Jesmond, and their residents; something from the vibrant arts scene, both on the Newcastle and Gateshead sides of the river – the regeneration and money that’s gone into the Baltic, and the Sage is enormous, and the largest selling art gallery in Britain (the Biscuit Factory) has had pieces by Damien Hirst for sale and sold; it’s hard to get tickets for music of any kind, at the Metro Arena, the Carling Academy, or the Sage, it all sells out – but we’re all poverty struck??

It was my impression that you could have taken the photos in this supplement in Manchester, London, Southampton, Birmingham, Glasgow, (well, apart from the seaside one!) basically anywhere, so what impression of Newcastle does this give?

parrpolygon (aka Martin Parr) says:

“It is great that my photos can wind up the likes of Caroline so much. I had no agenda apart from looking round, finding photo genic situations and I believe that I am entitled to shoot what i like. I do not think the Newcstle supplement is down on Newcastle. In her list of what I photograph, she very conveniently misses out the more middle class subject matter, perhaps she had an agenda?”

Posted in MISCELLANEOUS | 1 Comment »

I must say that I’ve been totally underwhelmed by Martin Parr’s much heralded photographic portrayal of ten British cities, which have been running as ‘special’ supplements in the Guardian newspaper over the past few months.

This weekend, the Guardian’s Weekend magazine ran a cover story with a twelve page spread showing a selection of Parr’s photographs under the title ‘Urban Splash- Martin Parr captures the essence of Britain’s cities’.

I’ve not seen the full set of photographs, however, if the magazine’s edit is anything to go by then they appear to be little more than an incoherent selection of snapshots hurridely collated, and furnished with uninteresting and often irrelevant captions. Aesthetically they seem very lazy indeed. Maybe he’s been too busy this year peddling Parrworld? (the largest exhibition to date of his work, which opened at the Haus der Kunst in Munich and is touring the world).

The whole project also appears to be very calculating in terms of its spin-offs, with various box sets (standard and deluxe) and calendars available from the Guardian website here.

I’m not one of those anti-Parr photographers, indeed I’ve long respected him as a practitioner and commentator, however it does seem that he’s missed a real opportunity to produce something interesting and illuminating about Britain, twenty years after the publication of his groundbreaking book, The Last Resort.

Much of his portrayal has certainly been seen as very stereotypical, as illustrated by these comments posted on the Guardian letters page –

“I was dismayed and shocked by Martin Parr’s supplement on Newcastle (British cities: Newcastle, October 27). He introduces his piece: “I first visited Newcastle in the mid-70s and I remember being impressed with Byker, a classic working-class suburb with a tight sense of community and steep terraces. I revisited Byker for this project and found the small shops were struggling, despite Aldi and the Gala Bingo doing well.” This shows he came to Newcastle with the notion of finding that quaint, parochial, grim-up-north picture of the Geordie struggle for survival – a dangerous stereotype to uphold.

Newcastle is no longer a bastion of British industrial power, but a multicultural metropolis often billed the London of the north because of the regeneration that has been applied to all areas of the city. Areas such as the Quayside and Jesmond have welcomed this regeneration, and have seen new life breathed into them, attracting young professionals and students alike.

There are many things Parr could have shot to highlight the urban evolution that is happening within this city. He mentions Grey Street and the stunning architecture of the city centre, but does not show it in any of his photographs. Then there are some of the many attractions that bring people to the city that he missed out in favour of outdated sentiments, such as the Laing Art Gallery, the Tyneside cinema, Blackfriars dining hall, the Tynemouth Priory and Castle, the Jazz Cafe, both universities and any one of the many bridges spanning the Tyne – I could go on.”

Nelson Iley, Newcastle upon Tyne

“Martin Parr’s supplement on Newcastle was billed as one of a series “capturing today’s urban Britain”. What he has actually done is lazily capture all the cliches of Newcastle from 30 years ago. In his 29 photographs, he manages to pack in bingo, greyhound racing, homing pigeons, a double dose of the derelict Swan Hunter shipyard, a greasy spoon cafe, two shots of hen nights, two lots of women with cheap drinks at the races, and a tattooed man prodding his barbecue. While all of the above go to make up some of the rich mixture of life in Newcastle, where are the other sides to the city? Where’s the chic city centre pubs and bars? Where are the 50,000 students? Where are the arts venues? Where is the growing multicultural community? Guess they would not suit the stereotypes Parr set out to portray.”

Graeme King, Newcastle upon Tyne

“Martin Parr seems to have arrived in Newcastle with all his stereotypes in tow, and to have regurgitated them for us with stock images of pigeon fanciers etc. Geographically, the photo essay was inaccurate. It was entitled Newcastle, but included Gateshead and North Tyneside – two areas distinct from Newcastle in the eyes of north easterners.”

Alison Grant and Anna Vaernes, Newcastle upon Tyne

You can see a selection of Parr’s images from the project on the Guardian’s website here.

I’d be interested to hear your comments on the work, if you haven’t already done so on the Flickr group Martin Parr We Love You!

Posted in OTHER STUDIES, REPRESENTATION | 19 Comments »

Quite belatedly, I’m reading Susan Sontag’s book On Photography (Penguin Books, 1971).

Just read this paragraph, which seems somewhat relevant to my last post….

“One situation where people are switching from bullets to film is the photographic safari that is replacing the gun safari in East Africa. The hunters have Hasselblads instead of Winchesters; instead of looking through a telescopic sight to aim a rifle, they look through a viewfinder to frame a picture….The photographer is now charging real beasts, beleaguered and too rare to kill. Guns have metamorphosed into cameras in this earnest comedy, the ecology safari, because nature has ceased to be what it always had been – what people needed protection from. Now nature – tamed, endangered, mortal – needs to be protected from people. When we are afraid, we shoot. But when we are nostalgic, we take pictures.â€

Posted in RESEARCH | 1 Comment »

“The subtlest and most pervasive of all influences are those which create and maintain the repertory of stereotypes. We are told about the world before we see it. We imagine most things before we experience them. And those perceptions govern deeply the whole process of perception.â€

Walter Lippman (1987) quoted in The Hollywood Arab

Still no baby yet so I’m going to take this opportunity to respond to a post I received earlier in the summer from a photographer in Italy who challenged my approach to We English. Notably, my decision to invite the general public to post their own ideas which I could then photograph. Here is their post-

Dear Mr Roberts

As a viewer the idea is really functional. As artist the idea it is a bit vicious. Are you playing smart asking people to help?! Finding by yourself events and situations is the main reason to be a photographer. You will be a translator of others ideas and inputs. Are you a politician of a self-thought photographer? And you receive funding as well! Yes definitively you are a bit of a politician.

Giuseppe Mascia, May 3rd 2008

My reply is loosely based on two interviews I did with Joerg Colberg on his blog Conscientious and Jim Casper on Lens Culture in July 2007 where I discussed my approach to Motherland (published: Chris Boot). A number of points I raised are important in helping to answer Giuseppe’s question, and will be fleshed out slightly here.

There were two main reasons for choosing to travel to Russia for my book project, Motherland. Firstly it was somewhere that had always fascinated me. I studied Human Geography at the University of Sheffield and a number of the courses I took looked at social, cultural and economic issues surrounding Russia and the former Soviet Union. Secondly, while there had been a number of important photo documentaries on Russia in the last decade, many were produced around the time of the fall of Communism, and tended to concentrate on themes surrounding disintegration and decay. I felt that the dialogue was very one sided and that the debate had moved on in recent years but photographic representations hadn’t.

ENCOUNTERING ‘THE OTHER’

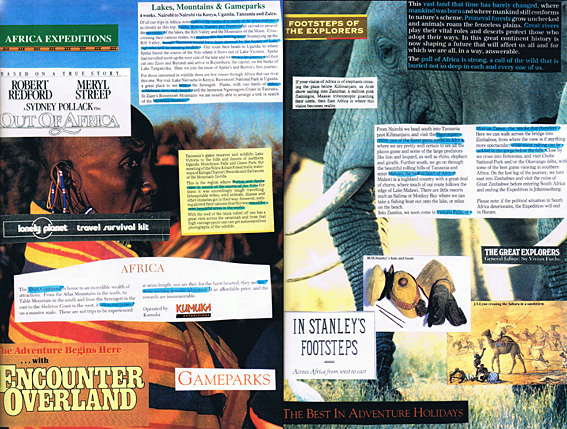

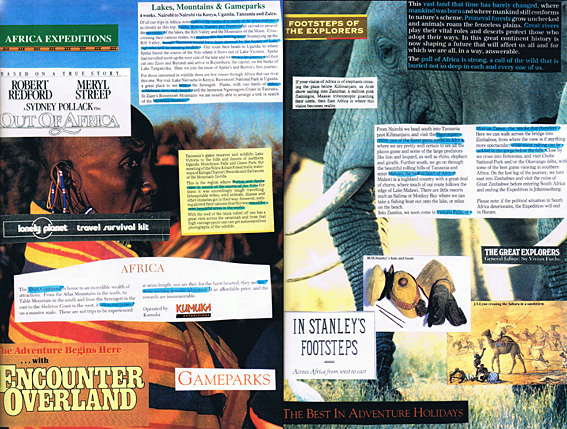

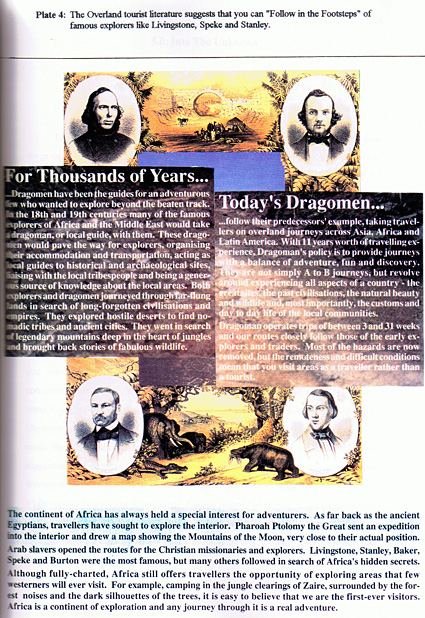

Samples of imagery and text used to advertise British overland tourist trips to East Africa.

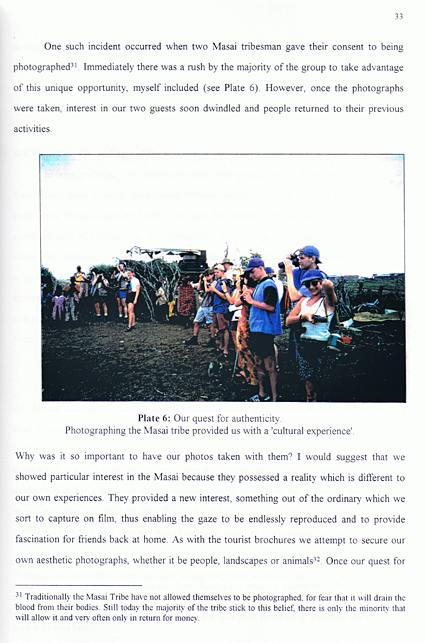

The problematic notion of representation and the question of how photographs are important to the construction of senses of place very much informed my approach to Motherland. The context for my approach was based on my BA Hons undergraduate dissertation. Published in 1995, my dissertation, entitled Encountering the Other: Representations and Readings of East Africa, was undertaken while traveling on an overland truck from Kenya to Zimbabwe with a group of Western tourists. Using Edward Said’s concepts of ‘Orientalism’ and ‘imagined landscapes’ my paper looked at Western representations of Africa, in particular those associated with the tourist literature advertising overland expeditions.

Ideas of imagined geographies and representation provide the starting point for Said’s discourse of Orientalism where he attempts to map the production and reproduction of myths and imagined geographies in constructing the inferiority of other people and places. Orientalism maps relationships between Occident and Orient. The Orient, Said argues, is contructed as an object for the Western gaze, a representation of ‘the Other’. Said suggests that although all cultures tend to make representations of foreign cultures, the preponderance of power has been on the side of the self-contituted Western societies.

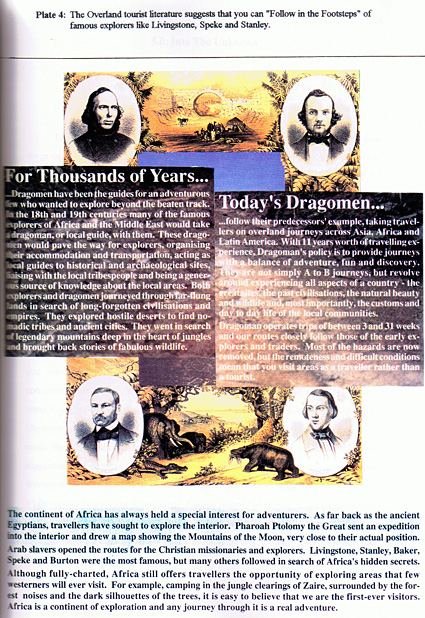

Tourist literature referencing the English explorers like Livingstone, Stanley and Speke.

The premise of my paper was that as Western tourists our imagery of Africa is one grounded in a colonial history; the 19th century European tradition of the expedition with adventurers such as Livingstone, Park and Thompson going out to explore and encounter distant and exotic lands. These images have been nurtured and re-enforced by the media and tap into a reservoir of ideas we have regarding colonialism, imperialism and representations of far away, exotic places and peoples. These ideas have also been appropriated by modern tourist companies in advertising ‘real’ African experiences; we, the tourist, are branded as adventurous travellers going out to experience the dark heart of Africa.

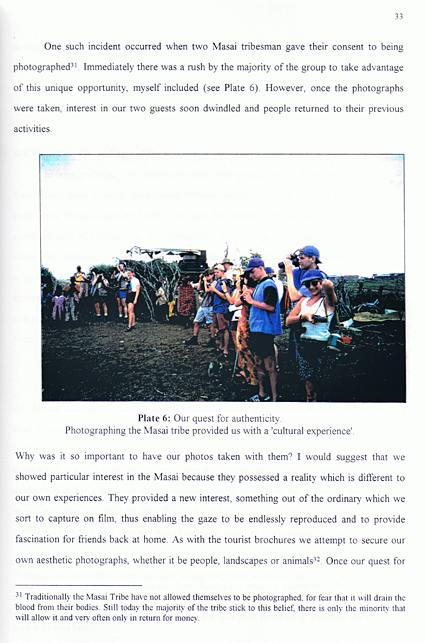

A page reproduced from my dissertation. The photograph is captioned: “Our quest for authenticity- Photographing the Masai tribe provided us with a ‘cultural experience.'”

My research concluded that even once East Africa had been encountered, it was very difficult to overcome the representations of place, engrained stereotypes if you like, that the individuals had brought with them. Evidence of which was presented in the photo albums that people produced at the end of the trip. These albums were representative of the way people remembered and ‘experienced’ East Africa, but the problem remains that many merely reproduced exotic images rather than presenting reconsidered and augmented perceptions of East Africa.

MOTHERLAND

Turning to Russia, I had my own preconceptions of this place. As a child, the Soviet Union seemed vast and mysterious. It took up most of the wall map in my geography classroom and was the vital region to capture to win the board game ‘Risk’. There were the glamorous KGB agents up against James Bond, and the Soviet-bashing propaganda of Cold War films like Red Dawn and Rocky IV. I marvelled at the photographs of Yeltsin aloft a tank outside the White House in Moscow on the collapse of the Soviet Union, ushering in a new but uncertain era.

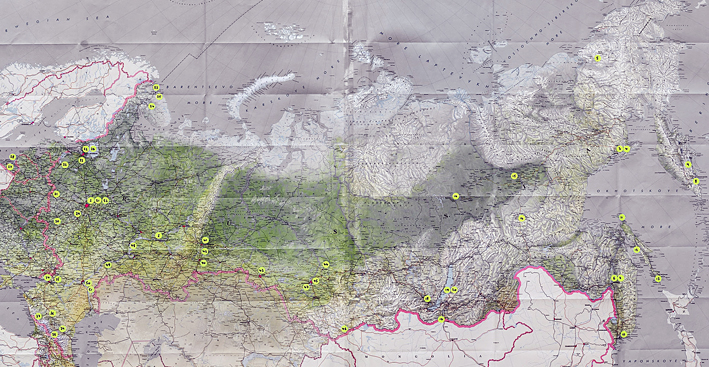

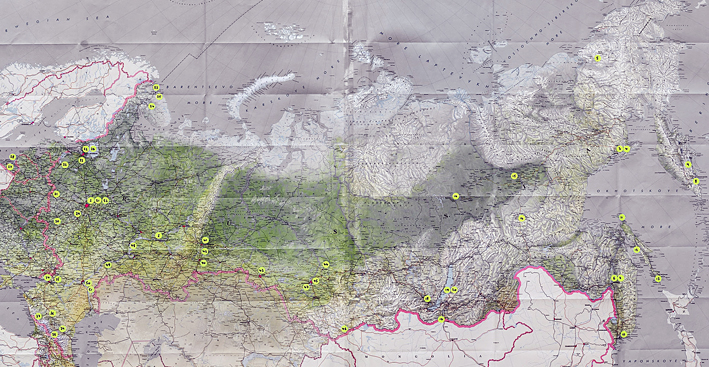

I’d only been to Russia once before, passing through in 1994 to visit my wife, Sarah, who was studying there. We decided that now would be a fascinating time to return, fifteen years after the fall of Communism. After researching the project for 18 months, we left London in July 2004 and spent the next 12 months travelling over 75,000km from the federation’s Far East, through Siberia to the Northern Caucasus, the Altai Mountains and along the Volga River. We finished in Moscow in July 2005.

Cover of Motherland, published by Chris Boot Ltd, March 2007

The resulting book is meant as a visual statement about the nature of contemporary Russia. It is my attempt to try and move beyond ‘imaginative geographies’ where the fantasies and preconceptions of the photographer are prevalent in the images to a representation of Russia that does not deny the problematic veracity of pictorial representation. Motherland responded to these questions successfully, in my own judgement, for a number of reasons. Firstly, the fact that I spent a continuous year in Russia allowed for a sustained and in depth engagement with the landscapes and people that I came across. While I travelled extensively and did not, as it were, conduct visual ‘fieldwork’ in a single location, the duration of my engagement enabled a spontaneity – I could respond to diverse events and situations, and was neither constrained nor driven by the specific agenda or timeframe of a photojournalistic assignment or news agenda. My preconceptions and expectations about place, for example, were altered the more time I spent there. If, inevitably, a visitor or traveller can only acquire a partial understanding, one that remains ultimately more that of an outsider than an insider, the grasp acquired by a questioning and persistent onlooker will nevertheless be richer and deeper than that of a more transient visitor.

I was constantly conscious about shedding my preconceptions and instead to be led by what I saw and experienced. If I had gone to Russia with the intention of documenting poverty, I would have looked for it – and found it. Instead I wanted to be as open as possible to new ideas and be surprised and challenged by what I found.

Map of Russia showing where we were each of the 52 weeks of the year.

It was very important that not all of the trip was planned. While I had a framework for the journey, I deliberately left at least half of the itinerary to spontaneity, thereby increasing the chance for my own stereotypes to be challenged and opening up new avenues of exploration that I could otherwise have overlooked. By staying in peoples’ houses, rather than just hotels, I was able to find people and places that I would never have otherwise come across. In some ways enabling me to become an insider rather than just a tourist.

One of the greatest challenges was being able to submerge yourself in some of the larger cities, notably in Siberia, when you often only had a few days. How do you really get a sense of a particular place in a short period of time? You turn up, you book into a hotel, and then how do you integrate yourself into the local society? It’s very difficult. One way I overcame this was by using homestays (sourced from the Hospitality Club website) where I sourced local families to stay with. Instead of just being overwhelmed by a place on arrival, I was immediately experiencing it from a local viewpoint. People introduced me to their friends and took me to places that I would never have found from a guidebook, or from our own research.

In Omsk we stayed with a University professor who gave me a tour of his University and took me to the All Russia Ballroom Dance Contest, which his daughter was competing in (which led to the portrait of Nikita and Rufina); in Rostov-on-Don I stayed with a local journalist who gave me a tour of the Cossack military base (which led to a portrait of a Cossack soldier on horseback); in Yekaterinburg I stayed with Sergei who took me for a banya with his son Kostya (which led to the image of them bathing naked in the lake); while in Kamchatka I spent five days trekking through the wilderness on horseback with Paval and Sasha.

Camping with Sasha and Pavel, Kamchatka, October 2004 © Simon Roberts

Sergei and Kostya after a banya, Yekaterinburg, May 2005 © Simon Roberts

To participate in the everyday rites of Russian life and society, to be an involved guest and a friend, as well as an observer and witness, turned out to be tremendously enlightening. On the other hand, the sheer magnitude of the country and the unusually large distances I covered allowed for a greater sense of conceptual and aesthetic comparison, of visual diversity and the cultivation of knowledge and photographic memory. Distance and time, therefore, ensured a naturally more rounded representation of people and place and a recognition of the complexity of my subject.

It was always my intention to combine both landscapes and portraits in the book. I used landscape photographs to provide panoramic overviews of the country, images that help to provide a sense of context, evoking peoples in their diverse habitats and surroundings. I was interested in making detailed pictures that the viewer could read, like a map, and find different cultural and social references in. Where possible, I tried not to crop out any significant details from the landscape I photographed.

Ballroom dancers, Nikita and Rufina, Omsk, May 2005 © Simon Roberts

Cossack soldier on horseback, Rostov-on-Don, April 2005 © Simon Roberts

These landscapes I countered with portraits that are fixed in a narrow moment of time and space and which take you in to the landscapes and provide a much more intimate experience. Most of my subjects were stopped and photographed in the environments where I came across them. I attempted to select as large a cross-section of people as possible, from all walks of life. The portraits were taken before engaging in conversation with the individual so I could remain as detached as possible and their expression appear deadpan. What becomes of greater importance are the details in the image; the clothes they are wearing and the landscapes they inhabit. The portraits are almost an anthropological study. As formal and static in nature as they are – I still think there is often an intimate connection between myself and the subject.

In producing a balanced portrayal it was important not to gloss over the cracks of modern day Russia. The Chechen Republic is still a profoundly emotive issue in Russian society and it would have been wrong to ignore or ‘sensor’ pictures from this region.. At the same time, I have included two very differing images in the book from Chechnya. While one shows the main outdoor market in Grozny in front of heavily shelled apartment blocks (in some ways a more typical image we’re used to seeing), the second shows a group of well-dressed Chechen women and their children in a part of Grozny that has been reconstructed. The latter is a surprising image in terms of our visual references, which have been dominated by negative photographic imagery. It was important that I showed both sides of the story.

Outdoor market in Grozny flanked by shelled apartment blocks, April 2005 © Simon Roberts

Group of Chechen women, Central Square, Grozny, April 2005 © Simon Roberts

Of course my view is still only a representation of Russia, “a construction that is contingent, partial and unfinished.†Duncan & Ley, 1993 (Place, Culture, Representation pub Routledge) and one which reflects my own set of ideas and biography. However, the book will now stand alongside many other bodies of work about Russia and, hopefully, form part of a wider photographic debate about contemporary Russia.

More recently I decided to create a website for the book and have a guest book page where people can leave comments about the work in a public forum. Here I am most interested in receiving feedback from a wider audience, particularly Russians themselves, where people can discuss how they perceive my representations of Russia.

Screengrab of the guest book page on Motherlandbook.com

WE ENGLISH

Turning to my England project, I won’t discuss much about the background to the work, which you can read on the blog here, instead look at why I decided to request ideas from the general public.

I had plenty of ideas about what I wanted to photograph for this project. Two boxes full in fact. At one point I employed a researcher to help me sift through the piles of cuttings, tourist brochures, books and leaflets I’d amassed. However, this is the point, these were my ideas. My representations of England. What I was interested in also discovering, were other people’s ideas about England; gaining a sense of their perceptions of this place, rather than just photographing my own.

Box of cuttings gathered during research for We English.

In all I received about 250 ideas from the general public. Ideas which, in themselves, provide an interesting snapshot of England in 2008. They illustrate what’s important to people and explore their own ideas on the notion of Englishness. They also enabled me to get a broader spectrum of coverage across themes and geographical locations and helped to find subject matter, especially on the local level, that could otherwise elude me. Rather than just photograph yet another Cheese Rolling Festival, a now cliched tradition, I wanted to find out what else happens in England that may not be part of the national conciousness.

In the end, I only probably used about 10% of the ideas provided. However, I’m considering printing them as an appendix to book, unedited, to sit alongside my own photographic representation of England.

Posted in RESEARCH | 1 Comment »